Damian O’Neill has been described as the greatest footballer that Cork never had. When the Bantry Blues man was at his best, a cruciate ligament injury in May 1997 stopped him in his tracks. Here he chats to KIERAN McCARTHY about his football adventure

***********

HERE we fucking go again, Damian O’Neill thought, as he was approached for an interview after a Bantry Blues U21 football game in the early 1990s.

Time to nip this in the bud, now.

That brilliant Bantry team was dominant in West Cork and beyond. Won three divisional U21 titles on the bounce (1992-94) and two county titles (1993-94). It was a team packed with future county senior winners. They were all over the newspapers. So too was O’Neill, their midfield general – but it was a different tag that was annoying him.

‘Any time there was a write-up in the papers they described me as the nephew of the great Declan Barron. That was the whole time in the papers. I was sick of it,’ O’Neill says.

‘Anyway, after one game a fella wanted to interview me and I just said, before I say a word if you mention Declan Barron in this interview I’ll never again talk to you. I am Damian O’Neill, I’m my own man, I’m not Declan Barron.’

That was, and still is, O’Neill’s style: no bullshit and straight to the point. It’s one of the reasons the boy from Bantry town rose to become the best Cork midfielder of the 1990s – and why one of Larry Tompkins’ first jobs as Cork senior football manager was to drive to West Cork to get O’Neill on board with the Rebels.

***

‘When I took over as manager in 1996 Damian was the best midfielder in the county and could have been in the country,’ Tompkins explains.

‘I wrote down things that I needed to do and getting Damian on board was on top of my list. I felt if I had him then everything else would click into place. I drove down to Bantry to meet him, to get him to commit.

‘In order to win an All-Ireland you need an extra ingredient – and Damien was that extra ingredient. He reminded me so much of Teddy McCarthy, the way he could hang in the air and field those balls.

‘He was a massive leader and I felt we needed that, he was a strong personality. He had it all. He had the physical attributes, he had the talent, he had the mental strength.

‘He came on board, put in an incredible effort, trained unbelievably hard, was in great shape and was exactly where I wanted him to be, but unfortunately he got a knock back at the wrong time when he was flying.

‘It was a blow to him, to the team and to me. Certainly, we didn’t see the best of him and what he could have been.’

***

O’Neill was 24 years old and at his best when his right knee buckled under him on May 18th, 1997. He had soared into the skies around Castlehaven late in the first half of Bantry’s Cork Senior Football Championship round one clash with Nemo Rangers, but when his feet finally touched the ground he knew he was in trouble. He felt a snap. Heard a crack, too. And he couldn’t stand.

‘It was like you stuck a sword in through my knee,’ he recalls.

‘The pain was excruciating for around ten minutes. I was trying to come back on after half time but I had no stability whatsoever in my knee.’

O’Neill discovered his fate a few days later after an arthroscopy at Waterford Regional Hospital by Dr Tadhg O’Sullivan: a severely damaged cruciate ligament. It side-lined him for the bones of a year.

‘We were flying it, we were really fit and I felt in my prime. That was a heartbreaker,’ he says – and that was the beginning of the end for his inter-county career. He had turned in some big performances in midfield for Tompkins’ Rebels during the 1996-97 national league. The signs were encouraging, but then it was snatched away for him.

It was a bigger loss for Bantry. He was their general. Their leader. Their main man. The captain of the Bantry team that won the club’s first-ever Cork SFC title in 1995. Even in his lowest moment on the field, O’Neill put Bantry first. As he was being carried off the pitch at Moneyvollahane after shattering his knee against Nemo, he was still firing instructions: ‘Make sure we fucking beat them.’

Bantry did survive that day, winning 2-9 to 1-11, but without their talisman in midfield they slipped to a shock loss against Na Piarsaigh a couple of weeks later. O’Neill’s importance to that Bantry team can’t be undersold, but Bantry’s influence on him is what made him the immense footballer he was.

***

O’Neill will never forget the basketball ring that hung on the wall in Declan Barron’s backyard in Georges Row, Bantry. The wars he waged with his uncle on that makeshift court helped shape him.

When he was 14 years old Damian’s parents spent a spell in America so he stayed with Barron. He never saw his uncle play, but heard the stories and legends that see two-time All-Star Barron – and his mythical ability to lord the skies – held aloft as one of the finest footballers ever to emerge from West Cork. A young, bullish Damian didn’t care about that reputation, he just wanted to beat the old fella standing in his way.

‘I was 14 so he was shoving for 40, or maybe a bit older. He was a lot physically stronger than me, he used to rough me around and I used to say “this fella is an old man and I am a young fella, so he’s not going to get the better of me”. I used to keep at it and at it,’ O’Neill says.

‘He hardly had to jump if the ball came off the rim, he’d shove himself into me, put up his hand and make me fight as hard as I could to get the ball off him – and I did. I had that battling nature in me from a young age.’

If O’Neill’s high-fielding ability can be likened to Barron’s, then his mind-set came straight from his father, the late Terry O’Neill who passed away in November 2019. Whatever Terry did, it was at 100 percent. No stone was left unturned. Damian was the same. He knew he had to work hard to improve as a footballer, so he did.

‘I wasn’t an all-star minor who would do wreck, like Kevin Harrington – he was very talented whereas I was ordinary. I knew what I had to improve on,’ O’Neill says.

‘If someone told me I’m not that good at this, I’d say nothing but I worked and I worked so I could do it. That’s what I did. I worked my ass off on my weaknesses to improve them.’

In his early years his kick-passing was inconsistent. The ball could just as easily veer out to the corner flag for company as it was to reach its intended target. The late Dr Denis Cotter christened one of O’Neill’s wayward efforts as ‘a scud missile’. That stuck for a while. It was Cotter’s psychology at work. O’Neill took the veiled criticism on board, worked hard on his kicking style, it improved and the joke was rarely heard again.

That relentless work ethic rubbed off on his team-mates all the way up. He led by example. Set high standards. And demanded high standards from everyone else. Think Roy Keane in a Bantry Blues jersey.

‘If I played shit myself, I’d be the hardest on myself,’ O’Neill says.

‘When I was captain I tried to lead by example. If fellas weren’t doing what they should be doing I’d give them the bollocking. But if I wasn’t playing well, how could I turn around and fuck the head off someone else?’

He was demanding, but he is an all-or-nothing character. He gave Bantry his all, and together they reaped the rewards. There were the two county U21 titles, the county intermediate title in ’93, and the two Cork SFC crowns (1995 and ’98). These weren’t one-man Bantry teams by any stretch, but he was the main man – and a focal point in the middle of the pitch.

***

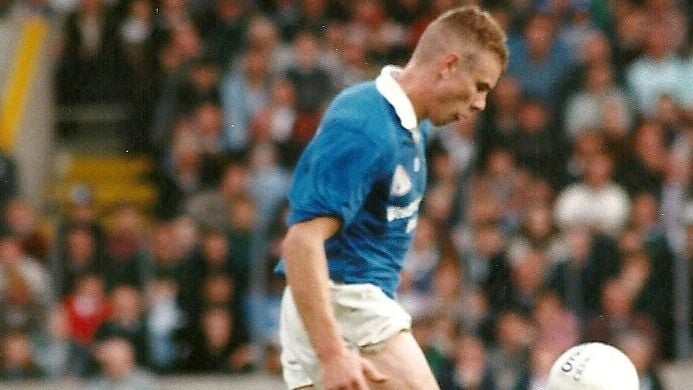

Damian O'Neill in action for Bantry Blues.

Damian O'Neill in action for Bantry Blues.

He wasn’t the tallest of midfielders but he was a goalkeeper’s dream. Just ask former Blues shot-stopper Des McAuley. O’Neill had this natural ability to read the flight of a ball and he knew exactly where to run to. Instantly, he was one step ahead of everyone else. And when he leapt into the sky, time slowed down. The ball would disappear in his giant hands. Majestic and mesmerising.

‘I stood behind him a few times when we would be doing kicking and catching drills and it was uncanny how he could see the flight of the ball,’ McAuley explains.

‘The next key thing was his ability to jump really, really high and catch the ball at the highest point of its trajectory.’

Those successful Bantry teams built their game-plan around O’Neill.

‘I didn’t have the longest kick-out in the world but I was accurate. We had a great relationship and understanding when it came to the kick-outs. In general the plan was to find space 20 to 30 yards anywhere around him, I would look for that space and 99 percent of the time he would claim the ball,’ McAuley says.

‘Damian wasn’t the tallest but he was extremely mobile so we would generally try and make him catch the ball on the move. We tried to avoid lumping the ball down the throat of him and a six-foot four-inch midfielder. Make them run and after 40 minutes they would be burnt out chasing him on the kick-outs.’

O’Neill reigned in the air and it was his midfield partner, the late Mick Moran, who dominated on the ground. In O’Neill and Moran, Bantry had the best midfield combination in Cork football at that time. They complemented each other.

‘He was the most talented footballer I played with,’ O’Neill says.

‘When we trained with the club we always marked each other – no-one else would mark him and no-one wanted to mark me either. Mick knew I’d beat him in the air but, Jesus, when I came to the ground did I know about it. He’d pulverise me.

‘He was the fittest player you’d ever meet. He never opened his mouth, we hardly ever spoke to each other, but I knew what Mick was going to do and he knew what I was going to do. I wasn’t too bad at fielding and any ball I didn’t catch Mick mopped up on the ground.’

Moran would die with his boots on for Bantry, O’Neill says, and one story comes to mind.

‘In 1998 we played Moyle Rovers in a Munster semi-final in Dunmanway, that’s a game we should have won. We always sat beside each other in the dressing-room but there wouldn’t be a lot of talk because Mick was a quiet fella,’ O’Neill explains.

‘One of Mick’s knees was swollen so (Dr) Cotter came over with a syringe and a needle and he took around three syringes of puss out of his knee, squirted it down on the floor, and Mick said nothing. I said to Mick, “is your knee at you?” “No, it’s grand,” he said. That was his attitude. Grand, after having three syringes taken out of it!’

Together, they were unstoppable and powered Bantry to heights the club had never reached before. It was O’Neill’s heroics with Bantry that saw Tompkins come calling in 1996 for his services. By then O’Neill was Bantry’s standout name, and had also won All-Ireland minor and U21 titles with Cork, the latter as captain in 1994. He had the football world at his feet. He was still only 24 years old. His stock was at its highest, but then he suffered that cruciate injury in May ’97 and it was never the same again.

***

‘Do I regret not being able to do more with Cork? Yes and no. If I wasn’t 100 per cent fit and committed, then I didn’t have the drive to do it,’ O’Neill explains.

He points to his comeback year, 1998, and the Munster SFC semi-final loss to Kerry. He wasn’t at 100 percent that day. He’d made his comeback earlier in the year but was then suspended for a couple of months after losing his cool in a Kelleher Shield game in one of his first matches back.

‘By the time we played Kerry in Killarney in July I had no football done. It was wrong of me to play and put myself forward. I was taken off that day because I was shocking,’ he says. That game, and his performance, stuck in his head afterwards.

He bounced back to captain Bantry to a second Cork SFC title in three seasons later in ’98 and the reward was captaincy of the Cork footballers for the following year. But by then he was being tormented by groin injuries. Still only 26, he should have been hitting top gear. Instead, he played two Munster SFC games that year and missed out on the run to the All-Ireland final. He was missed.

O’Neill, rated as the finest Cork midfielder of his generation, played a total of three championship games for the Rebels.

‘Unfortunately Damian didn’t get enough out of himself at inter-county level,’ Larry Tompkins says.

‘He had it all and he had the qualities of a leader. If Bantry didn’t have him would they have won those counties? No. That’s something very special, that’s within the player.’

O’Neill admits now that his heart just wasn’t in the inter-county set-up. It was taking its toll. He was self-employed in the construction industry, left home at 7am in the morning and worked through until 6pm, and then had to take a three-hour round-trip to county training. Many nights he wouldn’t see home until 11pm. The training, the commitment, the travel, it was a hard slog.

‘My attitude was if I can’t give it 100 per cent then I won’t do it at all,’ he says.

His Cork senior career petered out, but Billy Morgan, after taking over in 2003, did make attempts to coax O’Neill, now 29 years old, back in.

‘I never really proved myself with Cork but if I went back I was going back against my will. At that stage I was late 20s, I wouldn’t say my best days were behind me but there wasn’t a whole lot of them left. There was a lot of mileage on the clock by then,’ he says.

‘It was hard to say no to Billy, but I’m straight down the line. The other thing I had in the back of my mind is that there was a lot expected of me as well. If I came back into the Cork team and they put me in, I might not have been 100 percent ready, like in Killarney that day in 1998.

‘I said to myself that I’m not going to go back unless I am 100 percent right. If I am 100 percent and give it everything but don’t play well, then I have nothing to blame. I didn’t want to go in, being 75 percent right, not playing well and they saying I couldn’t do this or do that because I was injured. I never wanted to do that, that’s the easy way out.’

The main man with Bantry never fulfilled his potential to become the main man with Cork. That doesn’t rankle with him though. He points to his Bantry medal haul. That success, those teams, those friends and those memories, that’s what he cherishes. The great times he shared with three men who have passed away in recent years, his father Terry, midfield partner Mick Moran and former trainer Dr Denis Cotter; three men who gave their lives to Bantry football and whose contributions will never be forgotten.

Moran lined out with O’Neill when Bantry won the 2013 West Cork Junior D football championship. That success saw some of the old gang – long gone from Bantry’s first team –back together. Timmy O’Mahony played that day, too. They beat Ilen Rovers after a replay. It was O’Neill’s first junior medal. Great memories.

These days the father of four, who owns and runs Droumleigh Construction Ltd, is involved with Bantry’s underage section, and is coaching the U13s alongside Damien O’Donovan, Sean McCarthy, Paddy Goggin and Kevin Harrington. He feels it’s important to give back to the club, but he’s not a fan of modern football.

‘The amount of training and drills they do now in coaching sessions, it’s too much. The most important thing to teach young lads that age is the basic skills of football – how to catch the ball, how to solo the ball, how to kick pass the ball,’ O’Neill says, before his thoughts turn to last year’s Munster SFC semi-final between Cork and Kerry.

‘I know it was great that Cork beat Kerry but it was the worst game of football that I watched in a long time. This thing now of 20 passes before they get past the half-forward line, it’s ruined it. The only positive was that Cork beat them. Go back to the days when Darragh Ó Sé fielded a high ball sent long down the pitch, that’s football.’

Many who watched O’Neill in his prime would agree there was no better sight than watching the Bantry man soar towards the clouds. That was Damian O’Neill. Not a nephew of. But his own man.