Street games were once a very cheap and carefree form of entertainment, though they could also be hazardous, at times. Still, there doesn’t seem to be any equivalent in today’s technology-focused world

PICKEY’, ‘Cosc’, ‘Chesies’, ‘Release’ and ‘Glassy Alleys’ – these were the delightful nicknames of some of the many street games once enjoyed by generations of children in Ireland, and documented in a recent podcast by Cork County Libraries’ Kieran Wyse.

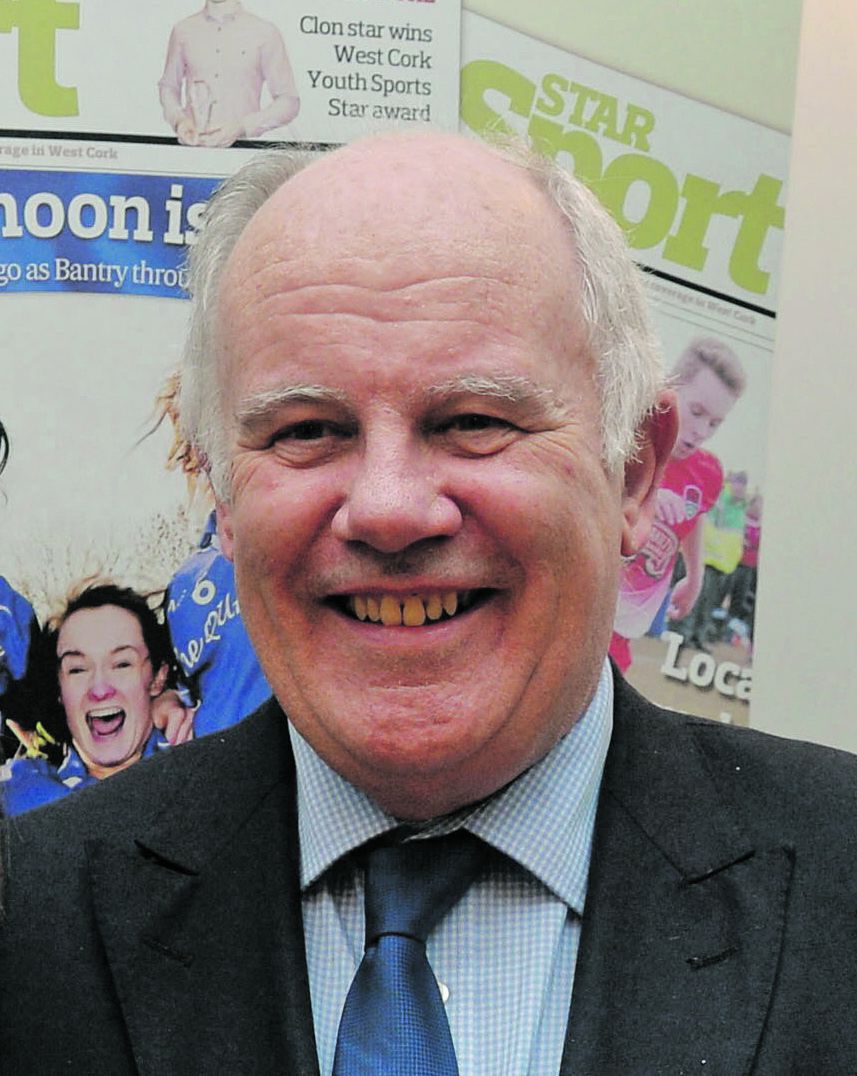

People brought up in West Cork today look back nostalgically on these games. Con Downing, retired editor of the Southern Star, recalled that when he was young, in the mid-1960s, it was mainly football on the streets before the cars completely took over the roads.

‘With a smaller ball, we would play rounders and handball against walls. We would regularly cycle eight miles from Dunmanway to Drimoleague to play soccer in the Railway Yard, and come home again for teatime. We were aspiring Pelés and Jairzinhos during the 1970 World Cup! We all became tennis maestros every year in July during Wimbledon.

‘There was semi-innocent, inter-street gang rivalry, with pitched battles being staged – using catapults and spears, and threatening burnings at the stake – inspired by war and cowboy comics. That nobody was actually killed or seriously injured during them was a miracle in those pre-health and safety days.’

Con Downing: ‘We all became tennis maestros every year in July during Wimbledon’.

Con Downing: ‘We all became tennis maestros every year in July during Wimbledon’.

Another West Cork man, John Leonard, who now lives in Cork city, agreed that some games were potentially dangerous. ‘If we had toy guns we’d play Cowboys and Indians, with homemade bows and arrows using twigs and string – luckily no eyes were damaged.’

Likewise, in the summer, children would swim in the sea without ‘parental supervision’, he noted.

While at school in Lisheen, he remembers the girls playing hopscotch – a game involving up to 20 children. ‘But I think they called it Pickey,’ he recalled. Each player tossed a stone onto one of six chalked squares, and then had to hop around the grid on one leg. The one who finished first could write their name in the furthest square.

‘Skipping was also popular,’ he said, ‘but boys didn’t get involved in either game, and generally played football, if a ball was available.’

Backyards being small, young lads had for years been belting footballs against street walls and, as in Bantry, ‘runnin’ from place to place from the peelers [police]’ noted The Southern Star, in July 1901.

Later, this newspaper warned against playing football in the street because of ‘the phenomenal growth of motor traffic in our towns’ – in November 1936.

Leonard recalls ‘a game similar to baseball’ with a small ball but without a bat. The ball was thrown and struck with the hand. ‘We called it ‘Cosc’. When no ball was available, a chasing game called Release was played, where one team chased the other and imprisoned them in a marked section of the yard.’

Management accountant Peggy Collins also reflected on carefree times.

Children in the street rolling ‘glassy alleys’ (Photo: Cork County Library/Local Studies )

Children in the street rolling ‘glassy alleys’ (Photo: Cork County Library/Local Studies )

‘We spent summers playing in fields, climbing trees, robbing apples, playing in hay and straw, making mud cakes by the river, while hopscotch enthusiast Terri Kearney, who manages Skibbereen Heritage Centre, remembered ‘going underneath a small bridge at our cross via a tiny dark culvert, no doubt populated by many rats … That was my idea of fun! – That, and running wild on our farm with one of our many dogs.’

Several street activities attracted both boys and girls. For a game of Glassy Alleys (marbles), some girls were apparently ‘sharks’, says Kieran Wyse in his podcast, and they could ‘deprive boys of their entire stock of marbles’.

Like most games, it was ‘inexpensive and uncomplicated, with minimal adult input’, he noted.

Furthermore, in communities of limited means, there was no shortage of ingenuity. Instead of a hoop, for instance, an old bicycle wheel could be substituted. Such make-do items were known in Cork slang as ‘mock-ya’ items, and in the girls’ game ‘Shop’, corks and silver milk bottle tops were used as mock-ya money. For ‘knock-around’ (football), mock-ya goalposts and corner flags were invented.

Many traditional games, concluded Wyse, were more sociable than today. Indeed, a child’s free time would often be interrupted with knocks at the door by friends asking: ‘Can you come out to play?’

Very different from today’s indoor video and computer-based games, a good few of which can be played by a single-player. Old-time street games, by contrast, encouraged mixing and integration, and, as Kieran pointed out, they ‘played an important part in the development of youth character’.

Which games can you remember playing as a child?

*The Street Games podcast can be found on Cork County Council’s soundcloud.com page.