Balance in history counts, says Dr Ida Milne, who recently addressed the West Cork History Festival, with a lecture telling the remarkable story of her Protestant family’s treatment during the 1798 rebellion in Wexford. Her speech also referenced the Dunmanway massacre of 1922

THE Decade of Centenaries produced the opportunity to re-examine the killing of thirteen Protestants in West Cork in April 1922, with historians parsing whether the killings were ‘simply sectarian’ as Professor Brian Walker has claimed, or that the evidence points to more complex reasons, as other historians like Dr Andy Bielenberg and Dr John Borgonovo have argued.

My family were involved in a similar event in a different tense period in Irish history, the south Wexford Scullabogue barn massacre of about 100 Protestants or Loyalists in the 1798 rebellion, as rebels returned to their camp on Carrickbyrne hill, hurting from the loss of 1,000 comrades in the Battle of Ross on the morning of June 5th.

But what of the periods between these tense times? How did communities integrate before and afterwards? Should we not also focus on that, rather than on what can often be unexplainable and irrational, happening as such atrocities do, in the height of war when emotions, rumours and misinformation play their own role?

My current research traces the impact of the 1798 rebellion and its aftermath on my grandmother’s family, the Elmes of Old Ross, through a collection of family letters saved by our father, King Milne, from the garret of Robinstown House, and other sources.

He was a 1798 historian and recognised the letters’ unique value.

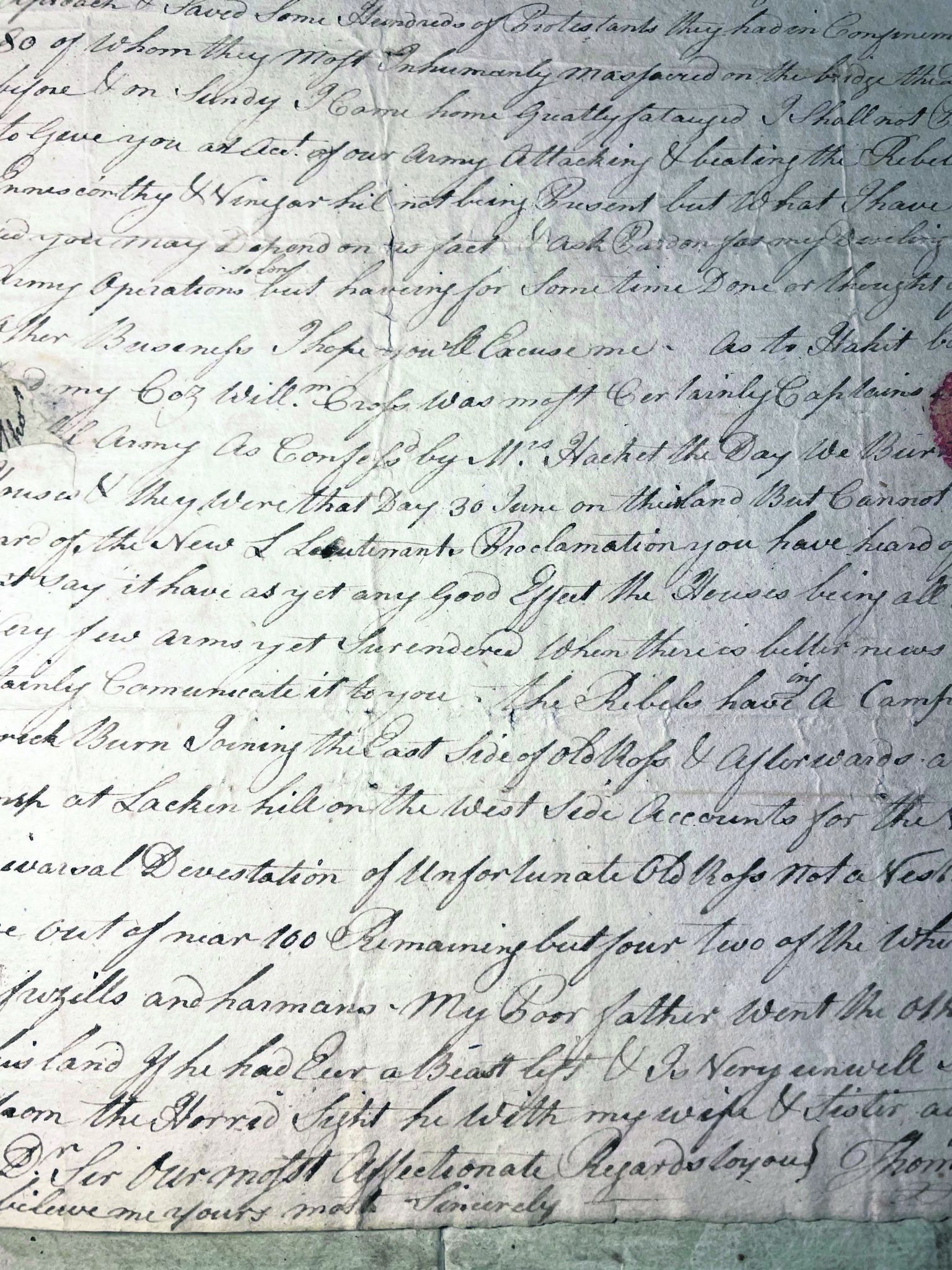

One of the family's letters, now in the National Archives.

One of the family's letters, now in the National Archives.Some were written at the heart of the rebellion as the writers feared for their and their family’s lives, and some 30 years after.

They were a Church of Ireland family, of Cromwellian descent. They lived around Old Ross, close to New Ross in south Wexford, for hundreds of years until the 1970s. Their home was very close to the Carrickbyrne Hill camp and Scullabogue. The letters are principally written by, or to, Samuel Elmes of Millquarter, a tenant farmer, and engaged with crises in farming as prices dropped in the year preceding the rebellion and farmers struggled to pay rents, the local United Irish activity and the yeomanry – and the whereabouts and safety of the family circle during the rebellion.

They cover a wide geographic range, discussing family members in London, Wales, North America and the Caribbean, often linked through connections with the Keogh shipping company of New Ross.

In June 1798, just a day before the Battle of Ross and the Scullabogue barn burning, a letter from yeoman Thomas Elmes, Samuel’s son, told of the Old Ross Protestants being evacuated in one hour and brought to New Ross for safety, where they were accommodated in houses ‘recently built’ by Tottenham, the local landlord.

One of our ancestors, then a child of three, was put into a churn of milk for safety during the trip, and later he bragged that he drank all the milk and as a result, never broke a bone in his life.

We are not told who brought them to New Ross, but suspect the neighbours had a hand in at least giving the warning, and not the yeomanry, as Thomas does not say so.

If rebel supporters saved us, such information would be too dangerous to put in a letter.

The Scullabogue barn burning is one that has received extensive coverage by historians, debating the who, why and wherefore. Tom Dunne, Kevin Whelan, and Daniel Gahan dealt with it in detail.

Gahan describes the dawn attack led by Bagenal Harvey on New Ross, and the devastating rout and loss of life for the rebels.

Of the 12,000 pikemen, 1,000 lay dead on the streets of Ross a few short hours later. As the rebels returned to their Carrickbyrne camp, they came across the barn at Scullabogue where (broadly) loyalists, many Protestant, were held, and shot or burned them to death, in retaliation for the anguish they felt over their losses in New Ross.

Over 100 were killed, including Millard Giffard and the Jones brothers, family connections mentioned In the letters. When I asked our Dad how to interpret Scullabogue, he said: ‘Difficult things happen in the heat of war’.

The letters documented Samuel Elmes dying, probably of a stroke, when he returned from New Ross to the farm and found his crops burned and animals killed. But broadly, the rescue plan had worked, and those evacuated to New Ross were not harmed.

However, I’m not just interested in what happened during the rebellion, but also for clues about how they settled back in after, and indeed what happened at other potential flashpoints, such as in 1914 when Home Rule was imminent, or during the War of Independence and Civil War.

In the letters and a farm accounts book – Dad hinted years ago that it was even more significant than the letters – we can see that the family moved back to the farm within weeks, and started restocking to replace the implements that were probably taken by the rebels as weapons.

We know, too, that our family did a lot of shared farming with neighbours, Catholic and Protestant hardly mattered.

The local graveyard in Old Ross is ‘mixed’, all neighbours buried in the community in which generations of them lived, even today. But not us, as the immediate family died out in the 1970s.

While living in Belfast in 2016, a chance meeting in the street with a city sanitation employee led to a discussion about Scullabogue. As I told my friend where I came from, he responded: ‘Many of our people were not treated well in Wexford.’

Surprised to hear awareness of the Scullabogue massacre at the far end of the country, I have since traced mentions of the Scullabogue killings at Orange lodge meetings in Belfast and Dublin in different eras when things get tense. For example, when the 1912 Home Rule Act was passed. The Dunmanway killings are similarly often cited as examples of inhospitability to Protestants in the republic, and yet it, too, is a community with a strong sense of neighbourliness.

While accepting these atrocities for what they are, I also feel it important that historians document other stories – of close community engagement and of neighbours throwing a protective cloak over Protestant families at tense times, and looking at the position across time.

Balance in history counts, particularly at a time when the question of a vote on unity comes evermore sharply into focus.

For me, and for King, one of the significances of the Elmes letters is that they show a different side to the more dominant Scullabogue story, which is usually portrayed as anti-Protestant.

While the letters certainly show fear about being in an area at the centre of a rebellion, they also point to survival and protection by neighbours – and of diverse attitudes within the family circle to the rebellion. We had both yeomen and rebels.

I think this longer perspective could well be applied to other such events in a way that would be beneficial to helping heal communities which have experienced such traumas. Kindness and respect in communities is as much part of our history as the more difficult events.

• The Elmes Letters were archived by Brian Donnelly in the National Archives of Ireland, and are on microfilm. Some were published by King Milne in ‘The Past: The Organ of the Uí Cinsealaigh Historical Society’, and available to the public on JSTOR.org.