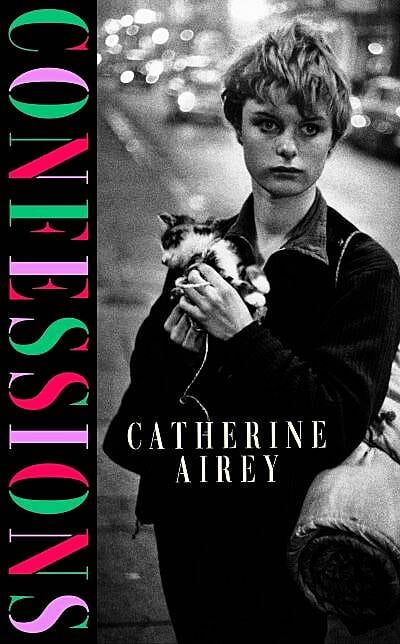

The much-acclaimed debut novel by Catherine Airey follows the lives of three generations of women from New York to rural Ireland and back again, writes Cammy Harley.

CATHERINE Airey’s grandmother, Margaret O’Donovan, was born in Dunmanway in 1921 and so her granddaughter has always had a special connection with West Cork.

Catherine says that 100 years after that fateful day, she cycled from London to Lough Hyne, in 2021, and subsequently stayed living in West Cork for three years.

‘I wanted to revisit the places I remembered from childhood holidays; the part of the world where my grandma had grown up,’ she said.

‘I didn’t have much money but found volunteer work through a scheme called Workaway, which gave me a bed to sleep in and food to eat. The work was outside, helping to restore a big old wooden boat which was over 100 years old,’ she explained.

‘We worked around the tides, and around the work I started writing Confessions. I wrote mostly from the boxroom I was staying in, lying on my single bed. I joined the Lough Hyne Lappers and swam through the winter in just my togs. I sat in Bushe’s bar in Baltimore with my notebook and a pint of Guinness as the sky turned orange over the harbour. I made edits upstairs in O’Neill’s coffee shop, then went around the Skibbereen second-hand shops.’

Catherine says that although she had been searching for a sense of her grandma, she was really building a life of her own. The novel itself evolved haphazardly.

‘I’d never written a novel before, and I didn’t have a clear idea of what I wanted it to be,’ she said.

‘I wrote 1,000 words a day, most days. I didn’t think too much about where it was going, but every couple of months I’d take stock and make decisions about what was or wasn’t working. This kind of thinking about the novel is important but can also be a distraction. You have to push through the thoughts that it won’t amount to anything, and the conflicting inclination to refine everything until it is perfect (it won’t be!) and just keep pressing on.’

Confessions is a well-researched novel, and Catherine says that she wanted the characters to be shaped by what was going on around them.

Confessions is a meticulously researched novel that follows the lives of three generations of women from New York to rural Ireland and back again.

Confessions is a meticulously researched novel that follows the lives of three generations of women from New York to rural Ireland and back again.

‘I was writing about places and times I didn’t have direct experience of myself, and I wanted them to feel authentic.

For the Irish parts in particular, it was important for me to reframe some of the ideas I’d absorbed as a child growing up in England, where Irish history was taught, at least implicitly, through a colonial lens.

There were two books in particular that I kept returning to: On Our Backs: Sexual Attitudes in a Changing Ireland by Rosita Sweetman, and We Don’t Know Ourselves by Fintan O’Toole.’

Catherine says that while she was writing she often consulted Google Street View and Wikipedia, but that her favourite internet source was Reddit because it’s so anecdotal.

‘I found posts where people had posted photos of offices in the World Trade Center before 9/11, threads where people recalled what New York City was like in the days that followed. I was really dedicated to finding out as much as I could, so I could inhabit my characters’ lives.’

The Irish parts of the book are set in Burtonport in Donegal and while Catherine wasn’t able to visit herself, she used Google Street View and found that it helped that she was living just outside a similarly small fishing village in West Cork.

Places that have a shop, a few pubs, but not much else, where everyone knows everyone and there’s always some kind of local intrigue circulating.

‘I try my best not to base characters on actual people I know or their stories – though I’m sure it bleeds in. It’s impossible to write a book without it being influenced by your own circumstances, and I did put a lot of myself into the narrators,’ she admitted.

‘Seeing the novel in bookshops is magical – it’s my favourite part of the process so far and I don’t think it will get old.

‘The excitement makes me feel very connected to my childhood self who would be so happy that I am a published author now.’