Almost four centuries ago this month, on July 28th 1631, the frightened villagers of Baltimore on Ireland’s south coast were brought into port in Algiers. They had been at sea since the horrors of June 20th, writes MARY McCARTHY – horrors which led to the establishment of nearby Skibbereen

THE moonlit night that changed Baltimore from a boom town to a ‘decaying fishing village’ was Sunday, 20th June 1631. That was when The Sack of Baltimore took place, according to Baltimore heritage walking tour guide, Paul O’Driscoll.

In 1625, the Baltimore Report described it as an English town, with very few Irish living there. In those days, the Irish remained in the countryside. This set the scene for the night the pirates came to snatch away the village’s people.

After the Flight of the Earls in the 17th century, the Plantation of Ireland took place throughout the country. Baltimore was no different. From Devon and Cornwall, English fishermen and their families were planted in this rural village of West Cork.

‘In those days, two distinct communities lived in Baltimore. At The Cove, and at the old area around the castle,’ explained Paul.

‘The Sack of Baltimore was a huge event, making headline news in Europe. King Charles I was incandescent with rage at how it happened. The effect on the village left the people fearful of another attack of the same nature. They went upriver to the smaller settlement of Skibbereen for more safety,’ according to retired journalist and author of The Stolen Village, Des Ekin.

‘On that Sunday before midsummer, the fascinating character of Morat Rais, alias Jan Jansen, having set sail from Algiers, arrived in Baltimore,’ explained Des.

‘This was a serious mission with two ships, 280 armed musketeers and pirates, and 36 guns. The ships anchored in waters off the inlet, east of where the Beacon is today. They arrived at nightfall, having come in over Roaring Water Bay, where they rowed boats silently with muffled oars, around the headland to The Cove, a half a mile from the village,’ he said.

After they arrived on the shingle beach, the pirates spread out quickly. Around 20 thatched houses, made of timber, were attacked. They torched the houses and set them ablaze. People were running out of houses to escape the flames. They were terrified to see the Turkish troops in full uniform.

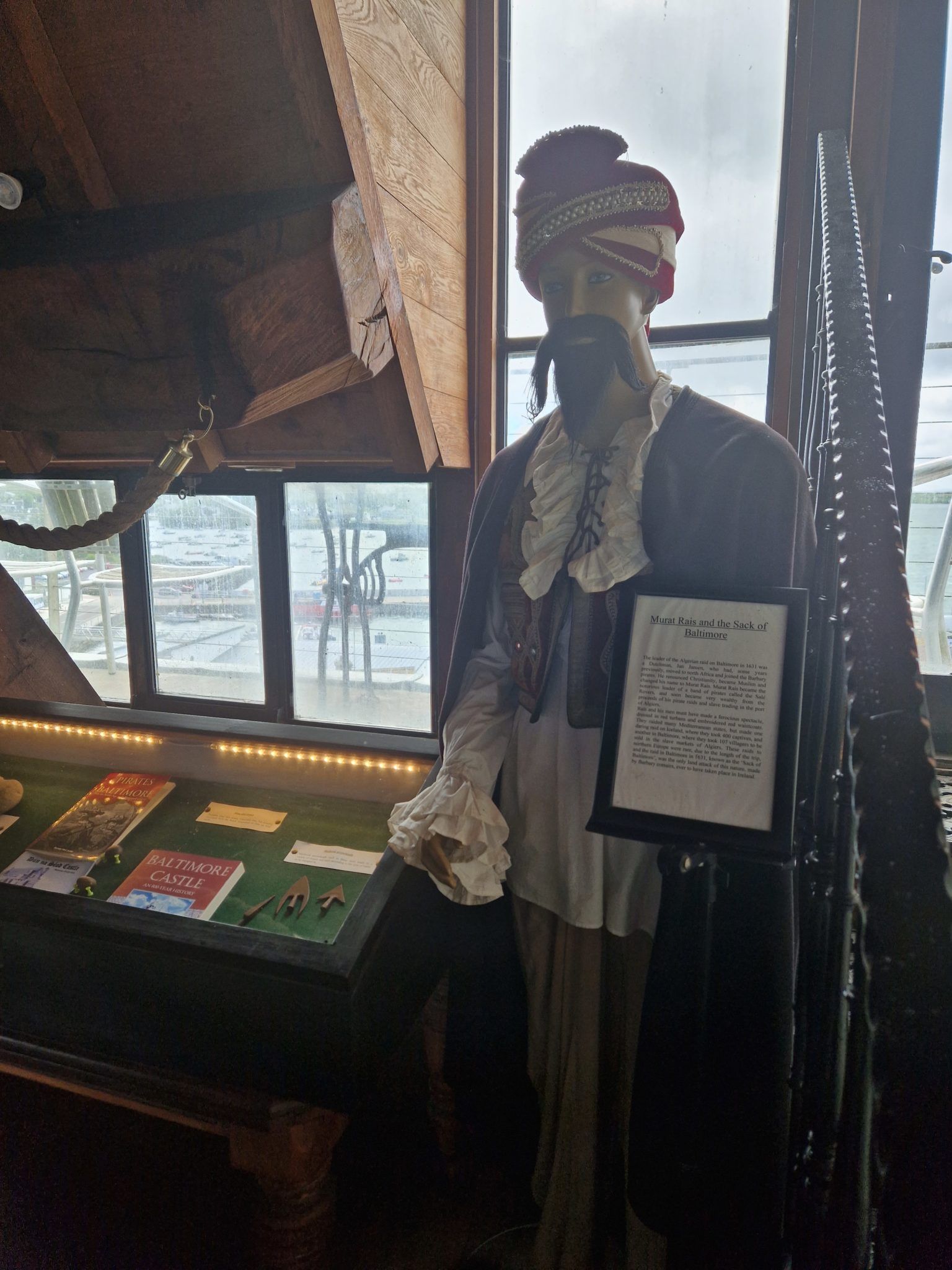

Morat Rais, Courtesy of The Pirate Exhibition at Baltimore Castle.

Morat Rais, Courtesy of The Pirate Exhibition at Baltimore Castle.

Only two men were killed. They took 50 children, but would have taken more, only a local man battered a drum as an alarm. Gunshots with muskets were fired. Morat Rais thought it was an army, and left quickly.

Those put on the ship bound for Algiers in North Africa included 107 prisoners – 50 children, many as young as the cradle; 30 women, and over two dozen men. Nine fishermen from Waterford were also captured.

All these poor fishing people were doomed to a life of slavery. They could not raise the ransom of £200 or £250. One woman, who must have been rich, was ransomed and returned home.

Sailing from Baltimore to Algiers took 38 days and the journey was uneventful. The log at arrival showed that they all survived.

Afterwards, 40 people died or converted to Islam. The 27 men taken were put into trades. They worked in the navy, as galley slaves, some as coopers, and more as sailmakers. These slaves contributed to their owner and kept some wages for themselves. Anything left over was money towards freedom, which was the incentive to work harder to buy it. The women became concubines or wives to wealthy men.

Author Des Ekin.

Author Des Ekin.

According to Des, an account by a French missionary priest who witnessed the public auction on slave markets, described it as ‘a pitiful sight’. Wives were taken away from their husbands, and children were taken away from their fathers. The record of prices fetched included women sold for £18. The price of six horses. And a pregnant woman for £32. At this time, there would have been syndicates of human investment. Female girls were sold for £50, with a return of £100 when grown up.

Baltimore Castle guide Paul O'Driscoll.

Baltimore Castle guide Paul O'Driscoll.

Fifteen years on, the government had nothing done to help these people. An envoy to ransom these Irish and English slaves was sent. Only two women took up the offer to return to Baltimore. Why so few came back is the question.

Des concluded there were many reasons why they did not return home. Some died. Under the rules of the country, those who had converted to Islam could not be ransomed.

Another theory is that they enjoyed life in Algiers: they had sunshine, and running water, and preferred life in the polyglot city. Some married. Children that were taken had established lives here.

The poet Thomas Davis recalled the intriguing event in his poem The Sack of Baltimore:

The summer sun is

gleaming still through

Gabriel’s rough defiles.

Old Innisherkin’s crumbled fane looks like a

moulting bird,

The summer sun is falling soft on Carbery’s

hundred isles.

And in a calm and sleepy swell the ocean tide is heard.