This week marks the anniversary of the first naval battle of Narvik, when Irish-born seamen were captured, together with their British shipmates. One of those was a man from Skibbereen, who was kept prisoner for five years for insisting he was British, and refused an Irish passport.

Devastation in Narvik harbour , a painting by John Hamilton, (Imperial War Museum, London)

Devastation in Narvik harbour , a painting by John Hamilton, (Imperial War Museum, London)

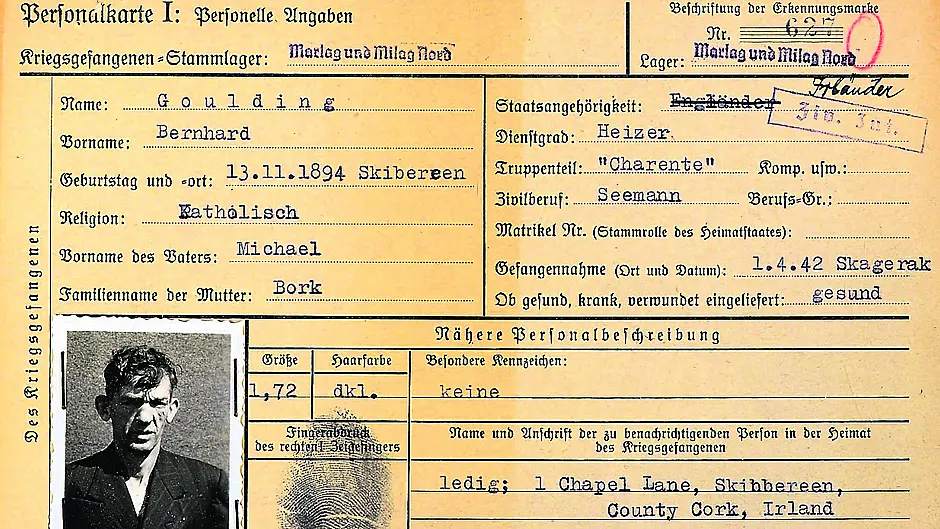

ONE of the 39 crew of the SS Romanby, a British warship seized by the Germans at Narvik, Norway, between April 9th and 10th in 1940, was Bernard Goulding of 1, Chapel Lane, Skibbereen.

‘Without suffering the loss of a single soldier or sailor,’ wrote historian David H Lippman, ‘the German army and navy had sailed 1,500 miles through waters dominated by the British Royal Navy and captured Narvik without firing a shot … taking five armed British merchant ships and their crews.’

Peter Mulvany, who chairs the Irish Seamen’s Relatives Association, described how Goulding and the others were forced to march 36 miles along a railway track through deep snow in bitterly cold weather.

Finally, they reached the frontier with neutral Sweden, where the Germans released them.

According to Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, they were given a ‘kindly reception, and over the next two years received regular allowances from the British Consul in Gothenburg.

In January 1942, along with five of his shipmates from the Romanby, Goulding joined the Norwegian warship, DS Charente, as a fireman.

Perhaps he needed paid work, maybe he craved adventure. Certainly, he was used to travelling widely.

His Royal navy record mentions him serving on five different British vessels between 1916 and 1922, when he was invalided out, and given a pension.

On March 31st 1942, the Charente sailed from Sweden with three other ships. Led by British shipmasters parachuted into Sweden, their mission – codenamed ‘Operation Performance’ – was to intercept the German blockade and bring ‘a valuable cargo of ballbearings and special steels’ into Britain, explained Mulvany.

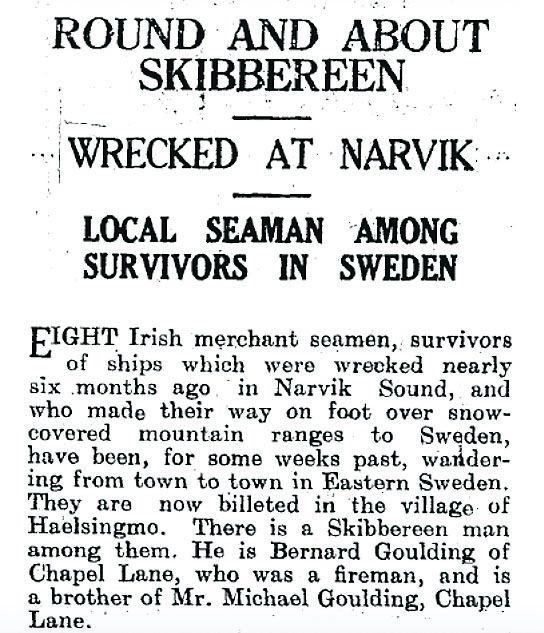

The story, as reported in The Southern Star.

The story, as reported in The Southern Star.

The following day, Goulding’s ship was attacked by German forces in the foggy Skagerrak strait, and sunk.

The West Cork man and other survivors were picked up by a German armed trawler and sent to the Merchant Seamen’s Internment Camp at Marlag und Milag Nord in Westertimke, Germany.

For the next three years, they became dependent on food parcels from the International Red Cross.

When William Warnock, chargés d’affaires at the Irish Legation, Berlin, heard that Irish-born British merchant seamen were being held in Germany, he started lobbying the German Foreign Office to release them, since Ireland was neutral.

On January 27th 1943, Goulding, and 31 other Irish-born British merchant seamen were relocated to Bremen-Farge concentration camp in Lower Saxony to await repatriation.

But the guards at Bremen-Farge were unaware of Warnock’s intervention, and demanded the men work.

When they refused, they were roughed up. Goulding (POW No 627) was required to put in 12 hours a day, probably helping construct a U-Boat shelter.

Conditions in the camp were brutal. The Irish Times (May 17th 1945) reported that the camp commander personally shot 16 prisoners, while others were beaten to death.

Five Irish-born seamen died from starvation or typhus.

Throughout his imprisonment, Goulding identified as British. He was based in Devonport, Plymouth, and even had ‘English’ written on his POW ID card; only later was it changed to ‘Irish’.

Claims by Irish-born seamen to be British astounded the Irish legation, and frustrated repatriation efforts.

On June 4th 1943, Goulding finally agreed to apply for an Irish passport, but his application was rejected.

Perhaps his insistence that he had ‘lost Irish nationality’ raised concerns.

After two years at Bremen-Farge concentration camp, in spring 1945, Goulding and 26 other Irish-born merchant seamen were put on a train for Flensburg in northern Germany.

But further difficulties awaited them.

Allied planes had destroyed a bridge en route, and their repatriation ship sailed without them.

The men were sent back to the Milag Nord camp. Only in May that year did Goulding finally return to Skibbereen, where he lived on Mardyke Street.

Bernard Goulding spent the rest of his career in the merchant navy, where his service record notes his ‘very good’ character.

Every week, he sent a contribution from his earnings to his semi-invalid brother, James, in Skibbereen.

In 1964, West Germany agreed to pay the British government £1m to distribute as compensation among British victims of Nazi persecution.

The British Foreign Office sent out appeals in newspapers, and on radio and television. Some 4,000 applications were received.

Goulding submitted his application for compensation on April 2nd 1966.

Twelve days later, he filed another claim for disablement. A supplementary statement, describing his time as a prisoner in Bremen-Farge, was returned on May 2nd.

But, on May 8th, 1966, Bernard Goulding died, aged 71. Next day, the British Foreign Office dispatched a letter, advising him that his compensation claim had been successful.

A month later, another letter was sent to his next of kin, James, asking for proof that he had a valid claim to Bernard’s award.

James was given two weeks to produce the necessary documents.

When no reply was received, the award was declared void. On July 6th, solicitors Collins & Kennedy in Skibbereen, took up the case.

But it is unclear whether any compensation has ever been paid to Bernard’s family.

• With thanks to Peter Mulvany for providing archive sources for this piece.