Emma Connolly reflects on the closure of the railway in West Cork over 60 years ago.

ON Good Friday 1961 the last trains left West Cork from Baltimore, Courtmacsherry, Bantry and Clonakilty.

That was 64 years ago on March 31st and the topic still prompts a range of emotions from nostalgia, to disappointment.

Rail came to West Cork first in 1849, when Cork and Bandon Railway opened its first line servicing Ballinhassig-Bandon, which was later extended to Cork city in 1851 after 300 men were engaged in the construction of the massive tunnel at Goggin’s Hill.

The biggest task was the construction of the Chetwynd Viaduct, 90 feet high and 440 feet long.

Over the course of half a century, lines were extended by various companies to Baltimore, Schull, Bantry, Clonakilty, Dunmanway Courtmacsherry, Kinsale and Macroom.

A large crowd on the platform in Skibbereen station after the last train arrived back from its final trip to Baltimore on Good Friday, 1961

A large crowd on the platform in Skibbereen station after the last train arrived back from its final trip to Baltimore on Good Friday, 1961

Clonakilty only got its service in 1886 after a campaign and by 1888, the Cork and Bandon Railway had become the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway.

Four years later, a line from Ballinascarthy to Timoleague opened followed by a further extension to Courtmacsherry in 1891.

A line to Bantry in 1892 was followed by an extension from Skibbereen to Baltimore the next year in order to stimulate the fishing industry.

The Cork and Bandon line was taken over by Great Southern Railways (GSR) in 1924 and by CIE in 1945, but by then, the closures had already begun, explained rail enthusiast Cathal Deasy who runs the popular West Cork Railway Facebook page.

‘For many years the West Cork lines had been under threat of closure.

The Civil War left railways scarred and the rapid development of the internal combustion engine during WW1 meant rail monopoly was gone,’ he said.

The view today and below as it was on Good Friday 1961 as the last lunchtime train made its way towards the ‘Cutting’ in Skibbereen.

A house has since been built on the line, and a mural commemorating the railway can be seen on the right of the modern-day photo.

‘GSR (who controlled all the local lines post-1925) stopped the regular passenger service to Macroom and closed the Kinsale branch in its entirety.

WW2 was not helpful either as during and even after it, coal was impossible to come by.

The Schull to Skibbereen line closed temporarily due to the coal shortage in 1947 and never reopened.

Passenger services were cut from the Ballinascarthy to Courtmacsherry branch but readers will remember that seasonal summer excursion trains went there up to the end.

The Macroom line was closed in its entirety in 1953 as the ESB built the Inniscarra dam, which flooded much of the trackbed coming into Macroom,’ explained Cathal.

In September 1960 the final hammer dropped: it was announced that all trains would cease the following year.

‘Railway men were confused as the line was in its best state in years, new diesel locos and railcars were working the lines and passengers got modern coaches. Even after the announcement, the stations were painted and maintenance continued,’ said Cathal.

Two trains side by side at Clonakilty Junction

Two trains side by side at Clonakilty Junction

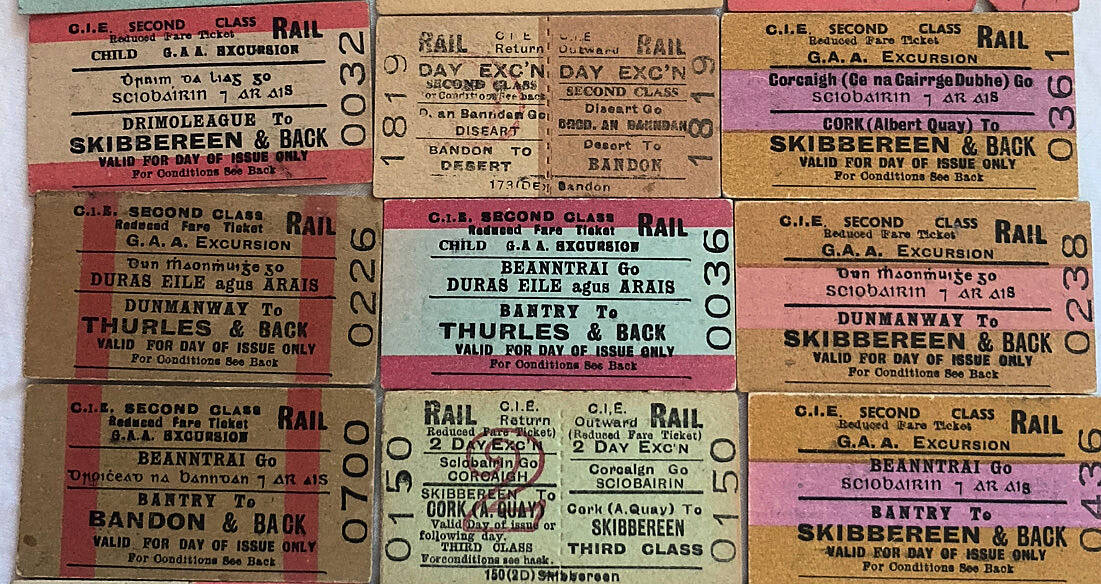

Tickets showing that you could once travel by rail, all the way from West Cork to somewhere like Thurles in Tipperary for a big GAA match

Tickets showing that you could once travel by rail, all the way from West Cork to somewhere like Thurles in Tipperary for a big GAA match

The announcement sparked huge protests by the Save our Railways Association (SORA), which collected 40,000 signatures from Clonakilty, Skibbereen, Bantry, Castlehaven, Rath, Leap, Ballydehob and Schull with the intention of the petition being presented to the president at the time, Éamon De Valera.

The petition stated that CIE had not done enough to ensure the economic viability of the West Cork railway moving forward.

‘The changeover from rail to road services will impose directly on the people of West Cork, a far greater financial burden than the relatively trivial loss on the railway imposes on the national economy at present,’ said a Southern Star report. It was to no avail: the whole network closed on Good Friday 31st of March 1961, with the last train leaving Cork at 6.09pm.

Former rail clerk, Raymond Good from Gaggin said it was a ‘crying shame.’

‘It was only losing a marginal amount of money at the time and look what it cost when investment had to be made in roads and buses?’ said Raymond, who worked in Bandon and Bantry before being transferred to Cork.

He remembered the ‘vibrancy, activity and excitement’ the rail brought to West Cork, the racing pigeons that travelled by rail from the North to be let out in Skibbereen to fly back, the special Legion of Mary trains that left Bantry at 3am on a Sunday to go to Knock, to return by 3am on a Monday, and the dedicated trains that ran to all the region’s agricultural shows.

Rail lifting started in April 1962 in Baltimore.

By 1964 it had reached Bandon and in early 1965, the lifting was complete.

‘A small section remained in and around Albert Quay for freight traffic until 1976, and that was lifted around 1984,’ says Cathal, who notes that there’s still plenty of evidence today of West Cork’s’ rich rail history, if you know where to look.

‘The main features, of course, being the famous Chetwynd viaduct, the viaduct at Halfway, Goggins Hill and Kilpatrick tunnels. Stations such as Upton, Bandon, Desert, Ballineen, Drimoleague and Baltimore all have beautifully preserved stations. In some places the line has been completely erased, but in other places you will find cuttings, embankments, bridges, telegraph poles and mileposts, and all that’s missing is the track.’

The West Cork Model Railway Village in Clonakilty celebrates and preserves the region’s rail history, and it marked its 30th anniversary last year.

Meanwhile, the Cork Commuter Coalition, a lobby group to promote public transport and sustainable mobility, set out a plan that would see all West Cork’s main towns connected to Cork city by electric rail in 2024.

The 37-page report identified three main rail corridors into Kent Station: a 33km Macroom line, an 87km line from Bantry through Bandon, Clonakilty and Skibbereen, and a 36km Kinsale route via Carrigaline, with a 4km spur to Crosshaven.

A key goal is to connect as many tourist sites on the Wild Atlantic Way as possible.

At the time, the group acknowledged the report wasn’t costed and has spatial and topographical challenges, but their objective is to make rail part of the area’s future, and not just resigned to its past.