Surrounded by ‘a girdle of surging, seething foam’, Fastnet is ‘perhaps more storm-beaten than any other lighthouse around our coasts’, reported The Southern Star in 1895. Many people once considered it ‘too weak to survive’.

This summer marks the 120th anniversary of the tallest lighthouse in Ireland and Britain – on Fastnet Rock, 7km south-west of Cape Clear.

Irish Lights is planning a commemorative event this summer for all the engineers, technicians and mariners who have ensured that Fastnet has operated reliably as a navigational aid since 1854.

The original Fastnet lighthouse is also celebrating its 170th anniversary this year.

Perched upon a rugged rock, ‘Ireland’s teardrop’, as it was known, afforded thousands of emigrants sailing to America during the 19th century a precious last glimpse of their native land.

Some 18,000 ships were wrecked off the Irish coast in the 19th century, and much of the impetus for building the original lighthouse came from the sinking of the Stephen Whitney, which struck West Calf Island on her passage from New York to Liverpool in 1847. Ninety-two lives were lost. Although there was a light on Cape Clear Island that fateful day, it was obscured by cloud and mist.

George Halpin, engineer to the Port of Dublin Corporation, responsible for illuminating Ireland’s shores, chose the highest point on Fastnet Rock to build his 91-feet high cylindrical cast iron tower. Work began in 1848, a tedious undertaking that cost £20,000.

Finally, on January 1st 1854, the 38,000 candle-power light began to flash – for 15 seconds, every two minutes.

Initially, Halpin’s tower held firm, but treacherous seas and gales soon exposed its vulnerabilities, and it began to ‘tremble like a leaf’, writes F. A. Talbot (Lightships and Lighthouses, 1913). First, coffee cups were thrown off tables. Then, large masses of rock on which the tower stood were washed away. Iron plates in the upper storeys worked loose and bolts sheared. Halpin’s building was on the verge of collapse.

Famous Scottish lighthouse builder George Stevenson visited Fastnet in 1865, and suggested ways to make the structure more stable. A cast iron casing was added around the tower to reinforce it in 1868.

The winter of 1881 brought storms that snapped off the upper section of neighbouring Calf Rock lighthouse, and smashed the glass in the Fastnet lantern. The event underlined the need for supplementary measures on Fastnet: a fog signal was introduced, and approval given to replace the iron lighthouse by a granite structure. The task of designing it fell to Irish Lights engineer William Douglass. Construction began in 1896. It proved a formidable task, with atrocious weather hampering works.

The new tower was built on a ledge, rather than a pinnacle of rock, and stood 147 feet tall, with a base diameter of 52 feet. A total of 2,074 stones of granite – each weighing up to 3 tons – were brought from Cornwall on a specially built ship, and dove-tailed together. ‘The jigsaw-style fit of its blocks has enabled it to withstand Atlantic storms’, explains James Morrissey (A History of the Fastnet Lighthouse, 2008).

There were seven floors, with storerooms on the lower ones, a kitchen on the fifth floor, and, on the sixth, bunk beds and lockers for the lighthouse keepers. The tower was capped by a lantern, 27 feet high, and 17 feet in diameter. A series of incandescent petrol burners emitted the equivalent of 1,200 candles, which were intensified by lenses to the equivalent of 750,000 candles. The lantern’s five-second flashes could be seen from over 20 miles out to sea.

The inauguration of what – at £84,000 – this paper later dubbed ‘the costliest lighthouse in the world’ (Southern Star, 24.02.1912) occurred on June 27th, 1904.

The original tower had been dismantled that March, and a temporary light installed. Its black base – now storing fuel – is still visible today on top of the rock. Later that year, the Marconi company installed wireless equipment on the roof of the new lantern, so that passing boats could be contacted.

Building work taking place on the second Fastnet Lighthouse, which was completed in 1904. (Photo: Irish Lights)

Building work taking place on the second Fastnet Lighthouse, which was completed in 1904. (Photo: Irish Lights)

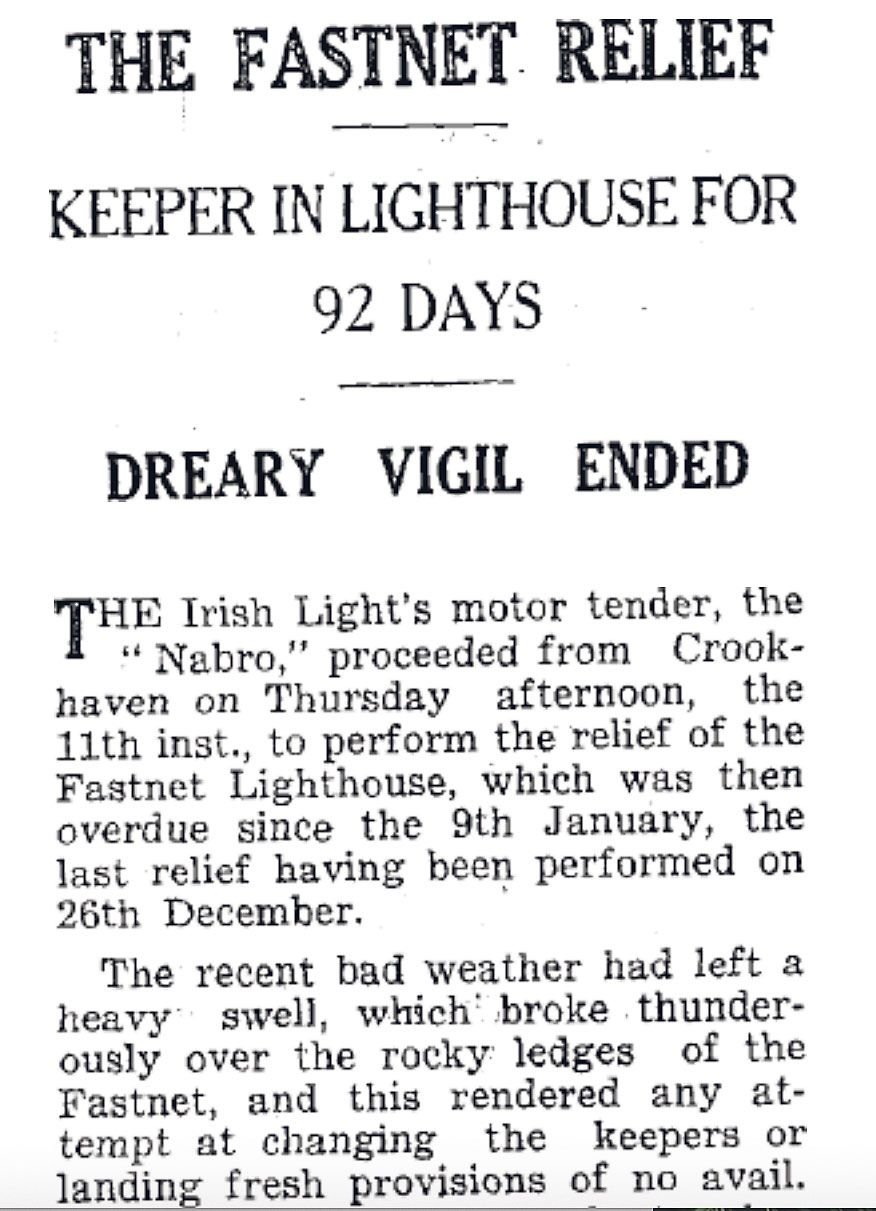

Six lighthouse keepers were employed – four at a time. Shifts were designed to last one month, but keeper James Hegarty could not be relieved for 92 days in 1936/37 due to ‘gigantic breakers’.

In his book, The Light-keeper; a Memoir (2012), another Fastnet Lighthouse keeper, Gerald Butler, recalls even the new lighthouse swaying during heavy swells: ‘The waves would hit the tower at about 50 miles per hour and crash right over the top’. Butler was on duty during the Fastnet Yacht Race tragedy (1979), when 19 men died and five yachts sank in a ferocious storm.

Over the years, the role of the lighthouse has significantly evolved, explains Irish Lights chief executive, Yvonne Shields O’Connor. These days, ‘sensors gather wind speeds, wave heights and water temperature’.

Gone are the keepers: an Irish Lights team visits Fastnet annually for maintenance. But some things remain unchanged. Like its 1854 predecessor, today’s lighthouse ‘makes the region safer for ships navigating Ireland’s treacherous southwestern maritime routes’. What’s more, believes Captain Dermot Gray, the sight of its beam ‘offers a sense of security and reassurance’. As singer-songwriter RP Gunn stresses in his Ballad of Fastnet, ‘Ships know they’re not alone’.