A blacksmith’s forge was not just a place of work in the West Cork of the 1800s and early 1900s – it also provided an important social hub for many communities, second only to the public house

TODAY we are used to the constant drone of motorised traffic. But in years gone by it would have been the occasional rumble of a horse-drawn cart and the distinctive highpitched ‘ping’ of a hammer striking an anvil that broke the silence.

In the 1840 poem The Village Blacksmith by HW Longfellow, he describes ‘a mighty man … with large and sinewy hands’ while in people’s imagination he stands surrounded by golden sparks, shooting upwards like fireworks from cherry-red iron.

In many West Cork districts, blacksmiths were leading tradesmen, and were known by their nicknames, like Johnny the Foundry, Mick of the Tricks or Jack Mac the Black. Slater’s Directory (1846) listed 15 blacksmiths in Skibbereen alone – compared with 12 butchers, 10 bakers and eight grocers. Only publicans outnumbered them. Even the tiny village of Ballydehob claimed to have had eight blacksmiths.

Sculpture of Billy O'Connell, the last of four generations of blacksmiths, at Innishannon Bridge.

Sculpture of Billy O'Connell, the last of four generations of blacksmiths, at Innishannon Bridge.

The forge was an important meeting point for the community, second only to the public house. Locals would gather and exchange news, always keeping at a respectable distance from the blacksmith and his apprentice boy with the bellows.

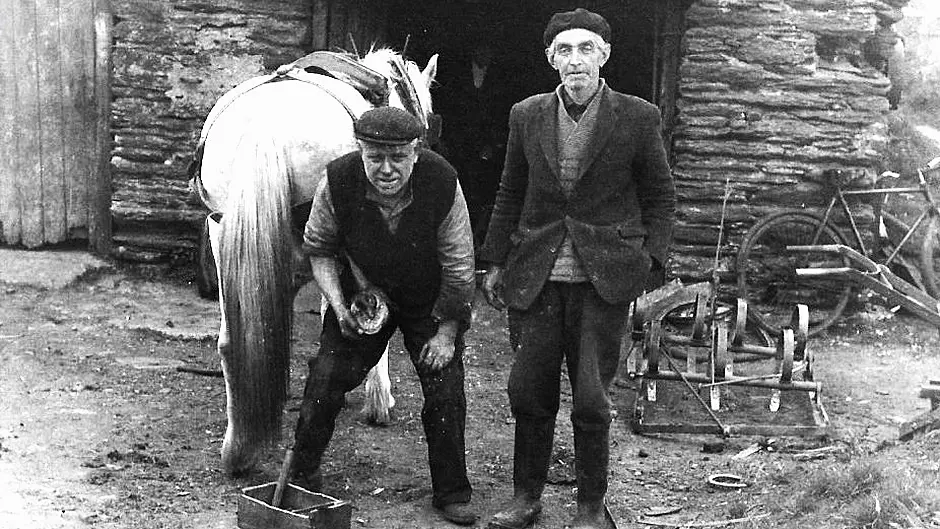

One of the blacksmith’s principal jobs was making and fitting horseshoes, as blacksmith Tim Cramer explained (Cork Examiner, 22 May 1978): ‘The old shoe is removed and the hoof tested, by tapping, for soundness. Then, facing backwards, and with the hoof held firmly between his legs, the smith pares and files it flat … ready for the new shoe. The almost white-hot iron is removed from the fire and beaten into shape on the anvil.

'Holes are punched for the nails, a few final taps and a trial fitting is made. With a hiss of steam the shoe is plunged into a nearby barrel of cold water to cool and harden … it is the end product of a magic mixture of elemental iron, fire, water, and consummate skill – of brawn, brain and artistry.’

The blacksmith’s work was not restricted to horseshoes. In the spring, locals would arrive with their harrows; in the summer, with their cartwheels, the iron rims of which had expanded and slipped off in the heat.

Blacksmith anvil on display in a little plaza opposite the Heritage Centre carpark, in Upper Bridge Street, Skibbereen.

Blacksmith anvil on display in a little plaza opposite the Heritage Centre carpark, in Upper Bridge Street, Skibbereen.

One Skibbereen resident, who recalls there were two or three blacksmiths behind the Horse & Hound pub alone, describes ‘The excitement about once a year when Jack Mac would be putting the metal hoops on the cartwheels … He’d spend an entire day fitting them … it was thrilling watching him submerge the wheels with the hot hoops into a big vat of water to cool them … the noise and steam and the general hubbub was fantastic.’

At harvest time, the blacksmith repaired mowing machines, and in the winter he had to fit wheels with frost nails. He would also supply farmers with iron gates and railings, spades, shovels and scythes. He made cooking pots for the housewife, and anchors for the fisherman.

‘The smith was the only tradesman who could boast that he made all the tools of his own trade, and of all the other trades as well,’ commented Eugene Daly in Ireland’s Own last year.

The old forge at Coppeen.

The old forge at Coppeen.

Some boasted a ‘speciality’ – James Santry from Lisavaird made pikes for the Battle of the Big Cross in 1798, while the first blacksmith mentioned in this newspaper – in 1892 – Eugene McCarthy, specialised in repairing ploughs at the Steam Mill Cross Foundry, in Skibbereen.

But one job that could get a blacksmith in deep trouble was attempting to counterfeit coins.

In 1933, Thomas Connor from Market Street in Bantry was charged with possessing moulds and a ladle used to make fake sixpences. Today, the need for blacksmiths has gone. Horses are a comparatively rare sight on our streets.

Although some forges have been restored – notably those at Coppeen, and at Ross – for the most part they have left no physical trace.

Their world, which had existed for centuries, has now disappeared, and a significant community hub has been lost. Horses still need to have shoes fitted by an expert who knows something about the structure of their bones and tissues.

But no machine can do this – yet. Speaking of his own art, Sean Galligan, in the Evening Echo in 1977, observed that these days the blacksmith ‘must go to the horse, since the horse no longer comes to him’.

Gone forever the familiar clink, clink, clink of the forge.

• With thanks to Cork Local Studies Library for additional information.