Riverstick native Denis Barry, refusing to accept the 1921 Anglo Irish Treaty, went on hunger strike in 1923, and 34 days later, in the Curragh hospital, he died. Family and friends will remember him fondly this month

BY ROBERT HUME

A century ago this very month, Ireland’s biggest hunger strike was entering its fifth week.

Kicking off with 462 prisoners in Mountjoy Prison in Dublin, it had quickly escalated to involve some 8,000 internees across the country, men and women, all imprisoned without trial.

The only ‘crime’ they had committed was to oppose the 1921 Anglo Irish Treaty for failing to deliver Ireland full independence.

Each had sworn an oath not to take food, or drink anything except water, until they were unconditionally released.

In the course of the strike two protesters died: one was Denis Barry from West Cork.

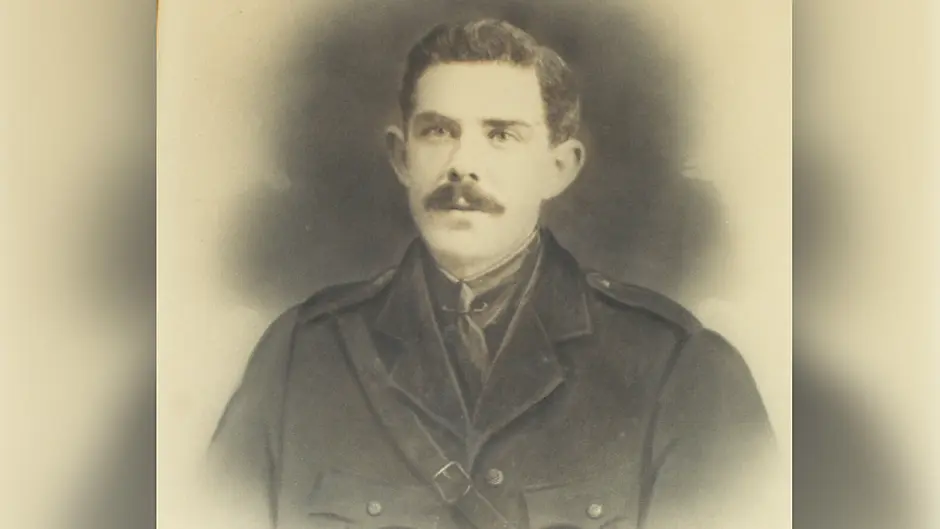

Holding a framed photo of Denis at the announcement of a special commemoration at Riverside Walk, Riverstick at 11.45am on Sunday November 19th was his grand-niece Celine Hyde. (Photo: John Allen)

Holding a framed photo of Denis at the announcement of a special commemoration at Riverside Walk, Riverstick at 11.45am on Sunday November 19th was his grand-niece Celine Hyde. (Photo: John Allen)

Barry was born on July 13th 1883 on the family farm in Cullen near Riverstick. At Ballymartle National School he learnt Irish and developed a passion for Irish history.

A great enthusiast of football, he found his forte in hurling. In 1913 he won the Croke Cup trophy with the Blackrock hurling club – The Rockies.

By day a draper’s assistant – first in Cork City, later in Kilkenny – at night Barry helped train the Irish Volunteers.

On May 3rd 1916, in the crackdown after the Easter Rising, he was arrested and detained at Frongoch Camp in North Wales. Returning to Cork City on July 24th, he was appointed staff officer to the No.1 Brigade of the IRA, and commandant of the Irish Republican Police.

When he refused to accept the Anglo Irish Treaty, Barry was rounded up and taken to Newbridge prison in Co Kildare on October 6th 1922, placed in K Block, and given the number 1014.

‘All the boys from Cork are here now,’ he quipped in a letter to his brother Batt.

Prison rations were sparse and needed supplementing with food from home. Barry asked his brother to send a pair of good, rubber-soled boots that he would pay for ‘when I get out’. But his mail was tampered with, and he received very few of the parcels or newspapers Batt sent him.

A year later, on October 17th 1923, along with about 1,700 others in Newbridge, all interned without charge, Barry took the drastic decision to go on hunger strike. After three weeks, he announced: ‘I am as strong as can be expected’.

In reality, he was fading fast, and on November 14th, the chaplain gave him the last rites. Five days later he was taken to the Curragh Military Hospital.

At 2.45am on November 20th, after 34 days without food, he died from heart failure.

The Curragh Camp Military Hospital, where Denis Barry died on November 20th, 1923 (Curragh History Facebook page)

The Curragh Camp Military Hospital, where Denis Barry died on November 20th, 1923 (Curragh History Facebook page)

Two days later, another hunger striker, Andy O’Sullivan (41) from Denbawn, Co Cavan, died in Mountjoy.

Barry’s body was hastily buried inside the hospital grounds. It was an extraordinary decision, because Barry was an untried prisoner. His elderly mother, still living in Riverstick, had been denied the chance to see her son, and to bury him with his own people.

Speaking for the government, General Richard Mulcahy insisted that the State would not give the opportunity of a ‘funeral demonstration’, which might inspire others to sacrifice their lives.

Only when the family took legal action was Barry’s body exhumed and transported to Cork city.

But there, Daniel Cohalan, Bishop of Cork, told priests not to let it enter any church. It was consequently taken to Sinn Féin headquarters on Grand Parade, where it lay in state.

The Southern Star of December 1st 1923 recorded Cohalan’s reasoning: ‘By the law of the Church, anyone who deliberately takes his own life is deprived of Christian burial … I shall determine the law of the Church strictly.’

On the very same page the paper printed the Republican perspective, which revered those ‘beloved comrades who fell in the struggle’ and whose names ‘will forever be enshrined in the hearts of the Irish people’.

The plaque which was erected in Barry’s honour in his home village of Riverstick in 1966.

The plaque which was erected in Barry’s honour in his home village of Riverstick in 1966.

On November 28th, Barry’s funeral cortège extended from Grand Parade to Brian Boru Bridge.

It was dark when the coffin reached St Finbarr’s Cemetery. In the light of oil lamps, Annie Mac-Swiney, sister of the late lord mayor of Cork, recited the rosary in Irish, and, since no priest was in attendance, David Kent TD sprinkled holy water over the grave.

The Last Post was sounded, and shots were fired in what one eyewitness called ‘one of the most imposing spectacles’ seen in Cork for years.

His nephew, also Denis Barry, wrote a biography of his uncle, The Unknown Commandant (The Collins Press, Cork) in 2010.