Tuberculosis figures for West Cork are currently higher than the national rolling herd incidence. Is this a temporary blip or a cause for greater concern?

MORE cows tested positive for TB in herds in Cork South West this year, than for the same period last year despite tighter disease controls, and a multi-million euro eradication drive by the Department of Agriculture.

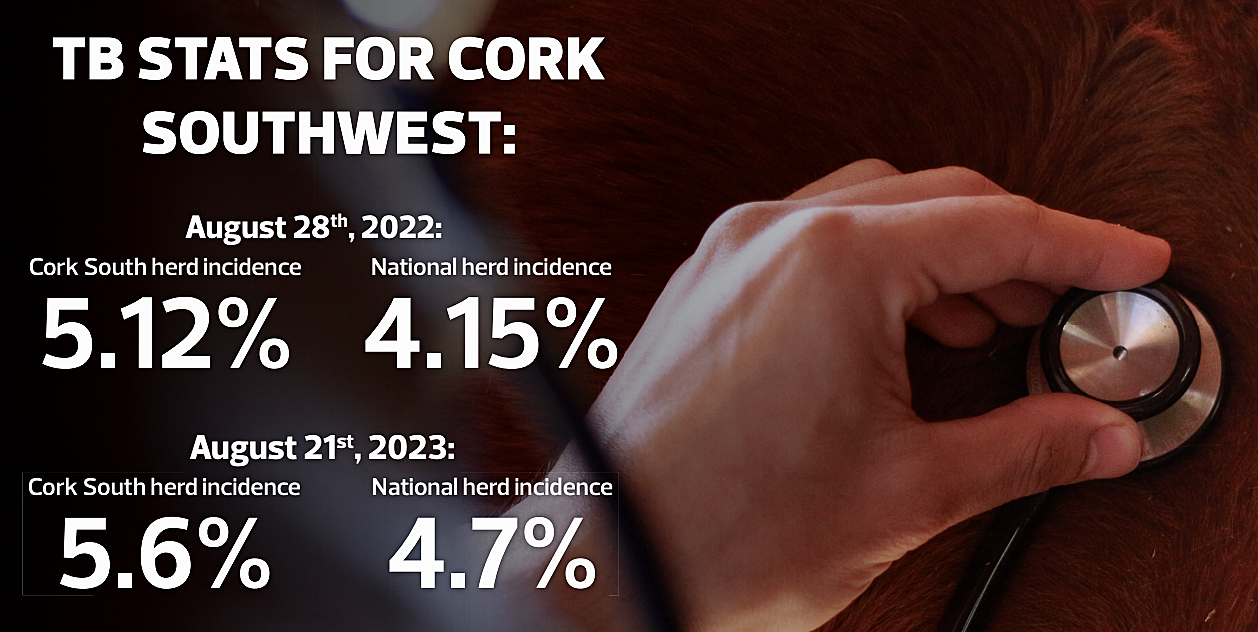

The 12-month rolling herd incidence for TB in Cork Southwest region was 5.6% by July, an increase from 5.12% for the same period last year.

There are 5,765 herds and 471,588 bovine animals in the region, which means that 322 herds tested positive for TB and were restricted.

The gures for the region, stretching from the Jack Lynch tunnel in the east to Dursey Island in the west and to the boundary with the river Lee in the northern part of the region, are higher than the national rolling herd incidence.

That stands at 4.7%, or 4,790 restricted herds, up from 4.13% or 4,470 herds in 2022. In 2021 that gure was 4.33% compared to 4.38% at end of 2020.

Reactor figures are also up nationally, reaching over 23,000 last year, which was the highest number since 2009. In addition to that, a report by the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) found that in 2021 Ireland was the EU member state with the highest levels of bovine tuberculosis.

While the increases are coming from a period where figures were at an all-time low, the uptick in cases has still caused concern among farmers in the region; as the nancial implications of being restricted, or ‘locked up’, or having a neighbour in that situation, are huge.

During a restriction, farmers can only sell animals to the factory, and the management of young stock can be problematic if their enterprise has inadequate accommodation to carry the extra stock.

New rules also came in on Feb 1st which state that cows of all ages, and males over the age of 36 months that are moving from farm to farm or through a mart must have been TB tested in the last six months, or be tested within 30 days a er the movement.

Ireland’s eradication programme began in 1954 when there was TB in about 25% of herds. It started out of necessity to allow the export of live cattle, which was the country’s main economic activity at the time.

An effective TB eradication programme often forms a key part of agreeing trade deals with foreign countries for Ireland’s beef and dairy produce.

Thus, its implications for international trade are huge.

There are three main sources of infection for cattle – the purchase of infected cattle, the presence of residual (undetected) infection within cattle herds and from wildlife (badgers predominately). The expansion of the dairy herd and more intensive farming are other factors.

Badgers were first identified as being susceptible to infection with Mycobacterium bovis (M.bovis), the bacterium that causes bovine tuberculosis (bTB), during the 1980s and the Department of Agriculture now has a badger programme in place to minimise the risk of badgers spreading TB to cattle. It involves vaccinating badgers in some areas where the risk posed to cattle by infected badgers has been brought under control and removing them in other areas where there are severe bTB outbreaks in cattle which have an epidemiological link to badgers.

IFA West Cork animal health committee representative Derry Scannell: 'As long as we have badgers, we'll have TB.'

IFA West Cork animal health committee representative Derry Scannell: 'As long as we have badgers, we'll have TB.'

Badger vaccination commenced in Cork Southwest in 2019. This year in the region, 190 badgers were vaccinated and 199 badgers were culled. A rolling sweep of all badger capture licences is undertaken over an 18-month period with increased emphasis on breakdown areas. Badgers are a protected species and are culled under strict licencing from the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Research carried out on bTB in deer in Ireland found that in certain areas, such as Wicklow where there are high densities of deer, cattle and badgers living alongside each other, the same strains of bTB can circulate between them. However, in most parts of Ireland including Cork Southwest there is currently no evidence that deer play a signi cant role in the spread of bTB to cattle.

To date in Cork Southwest, postmortems of deer carcases have all proven negative for TB.

Meanwhile, in 2021, Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue launched a new Bovine TB Eradication Strategy 2021 2030, and pledged to eradicate the infection by 2030. Its implementation is overseen by the Bovine TB Stakeholders Forum with support from three working groups on science, implementation and nance. Farming stakeholders have expressed some concern about the strategy as it’s understood the EU is to cease its funding after this year.

ICSA Animal Health and Welfare chair Hugh Farrell has said it is high time that the Minister for Agriculture faces up to the reality that he needs to secure additional funding if we are serious about eradicating TB by 2030.

‘At the TB Forum, the Department strategy has been built around going all out with more draconian measures in the belief that this can deliver success by 2030. Farm organisations are taking a constructive approach because TB has imposed so much pain on farms for several generations. But this cannot be done on the cheap, and if we want to gain a bit of forward momentum, now is the time to provide the support with a view to saving money in the long-term.’

IFA West Cork animal health committee representative Derry Scannell is unconvinced of reaching that 2030 target.

‘TB has always been a blight on the land and the problem isn’t getting any better,’ he said.

‘Larger herds, and improved habitats for badgers in our hedgerows are all contributory factors,’ he said.

The removal of forestry which encourages the badger to move about is also an issue, he said.

As a dairy farmer himself he spoke of the dread associated with the test. All farmers must have one test a year, but depending on individual circumstances a farmer can be locked into a testing regime every few months.

‘It’s a really stressful experience for the farmer, and the animal and that’s re ected in milk production the week of the test,’ he said.

As dairy herds have expanded in recent years, the economic fall-out of failing a test is huge, he explains. Compensation covers animals that fail and levels have increased, but not to labour, feed etc of animals that can’t be sold.

‘And that’s presuming a farmer has housing for the animals. It could be an animal welfare issue,’ he said.

Acknowledging that testing is essential, he said the skin testing regime needs to be made more robust.

‘Findings can currently be inconclusive, and that’s frustrating,’ he said.

‘The bottom line is that as long as we have badgers, we’ll have TB. The Department is doing their best, they’ve spent millions on this, but we’re no nearer a solution than we were 50 years ago. There’s no way of vaccinating all badgers, because there’s no way of finding them.’

He urged farmers to remain vigilant and notify their district veterinary office if they see badger activity on their land.

A wildlife app is also available from the Department’s website which allows them to electronically pin-point the location of a suspect badger sett. A Department wildlife officer will follow up on all notifications.