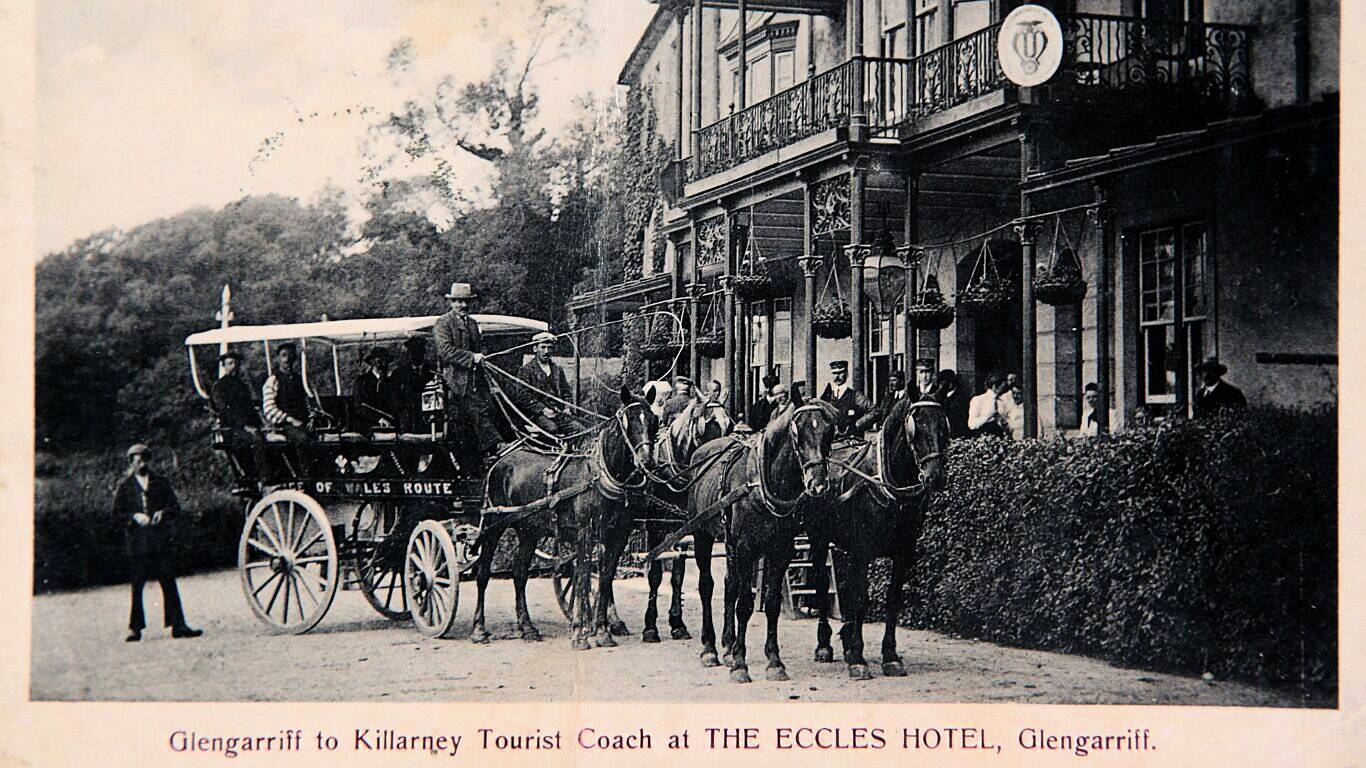

The news that the iconic 57-bedroom Glengarriff hotel, which has hosted a long list of celebrity guests, is up for sale, has prompted memories of its colourful past

THE moment guests scale the top step and venture inside the entrance hall of the Eccles Hotel, they are welcomed by a roaring coal fire.

Sparkling chandeliers cast flickers of light over portraits of two Irish glories: to the right, William Butler Yeats, to the left George Bernard Shaw, who appears uninterested in a vintage ‘His Master’s Voice’ horn gramophone in the corner.

On the wall beside the original porter’s lodge are suspended two wooden sticks to hang newspapers, complete with truncheon-like handles and leather straps. A gleaming 1921-style candlestick telephone and a Georgian longcase clock stand a few steps away.

An image of the former hotel.

An image of the former hotel.Walking down the corridors, visitors can observe neat signs in curly black calligraphy: ‘Please mind the step’, ‘Children must be accompanied by adults when using the lift’ and – nestled in a blanket box – ‘To have, To hold, In case you get cold’.

Outside the Yeats Suite, Irish-born actress and singer the late Maureen O’Hara peers down curiously from a gilt-framed photograph. Beneath, a navy blue and gold-striped chaise longue – apparently her favourite chair when she visited the hotel from her nearby home Lugdine, before she moved to the US and it was sold on.

Close to the dining room, on a walnut-panelled desk, sits an Adler Gabriele 25 typewriter, and alongside, mounted on a tripod, an imposing telescope with a chained brass lens cap keeps watch over Bantry Bay.

Today’s ‘Eccles Hotel and Spa’ offers a ‘Lazy Days Seaweed Bath’, a ‘spiced mud wrap’, with other ‘revitalising’ and ‘pampering’ experiences.

In fact, the hotel has always had wellness at heart. An eminent 19th century physician, Dr Noel Guenau de Mussy of Paris, wrote: ‘To invalids suffering from pulmonary complaints… The Eccles Hotel, which stands in a sheltered spot, and in extensive gardens, is faultlessly situated for a winter resort’ (Skibbereen Eagle, November 1882). Many fellow doctors recommended bathing in seawater, and the Eccles provided guests with a private pool, which was out front. In 1916, when owner Mrs Bryce converted the hotel into the ‘Queen Alexandra Home of Rest’, these guests were wounded soldiers returning from the

trenches.

The chaise longue outside the Yeats Suite which was a favourite of former Glengarriff resident.

The chaise longue outside the Yeats Suite which was a favourite of former Glengarriff resident.After the War, Mrs Bryce rented out the hotel garage to boys and girls from Glengarriff Irish College as a hall for Irish dancing.

But in August 1920, all ‘tripping the light fantastic’ ended abruptly. At 3.30 am on Sunday August 15th 1920, came shouts of ’Get up, get up! The hotel is on fire!’. Guests rushed outside in various stages of undress. The garage was in flames. A motorcycle, a cart, and a new motor car inside were ablaze.

‘The whole place seemed to have been well soaked in petrol before being set alight’, commented the Cork Examiner’s Glengarriff correspondent. The garage quickly collapsed into a heap of ’smoking ashes and twisted iron work’: the beautiful motor car, ‘placed there only a few hours previously’, reduced to ‘an utter wreck’. The blaze was a mystery, but fingers pointed to the British police.

Maureen O'Hara

Maureen O'HaraFortunately, the hotel itself went unscathed, including its famous library which housed valuable literature in French, Italian and German, and ‘important and scarce books of reference on the industrial resources of Ireland’ (Ward & Lock Guide to Cork,

1885).

Its collection was ‘unique’, confirmed American artist Harold Speakman, who visited the library on his tour of Ireland in 1924. ‘Here were… Disraeli’s Amenities of Literature, Voyages & Travels by Captain Cook, Pilgrimages to the Spas by Dr Johnson…’ A fireplace and armchairs at one end of the room provided a cosy hub for conversation.

The newspaper rods and, below, a 'candlestick' telephone in the lobby.

The newspaper rods and, below, a 'candlestick' telephone in the lobby.

Speakman recalls his two library companions: one ‘deadly tired and perhaps a little ill’, another a ’boyish-looking’ gentleman sporting a light-blue cravat and ’excitable white hair’. They discussed the dangers of underground railways, newfangled tinned food, and over-eating.

Situated in a remote spot, the Eccles would become still more isolated at night. Until 1948, the telephone service was cut at 10pm, making ‘Glengarriff 3’ uncontactable. With a library, ballroom, billiard room and conservatory, the hotel offered the perfect setting for a Cluedo-style murder. And there was one.

Jeremiah Collins (39) had stepped up in the world from farm labourer to Eccles Hotel porter, carrying guests’ luggage to and from their coaches.

The hotel's Victorian seawater pool.

The hotel's Victorian seawater pool.But any future aspirations he may have had were dashed on Friday September 22nd 1922, when he was kidnapped from his home in nearby Hollyhill. On New Year’s Eve his younger brother Daniel found Jeremiah’s body on Derrycreigh Mountain. It was in too poor condition to work out what had happened to him, but his death certificate records that he probably died from gunshot wounds.

Ghosts visit the Eccles Hotel today, ‘but only friendly ones’, a senior member of staff confided to me. Directly behind the porter’s lodge, where Jeremiah Collins was based, lies the hotel’s ‘Harbour Bar’. It’s in there that one of these ghosts has been sighted, sitting at Table 3 ...!

• Scoil Fhiachna Parents Association will host a free Christmas Fair at the hotel on Sunday November 24th from 12 noon to 4pm.

• Scoil Fhiachna Parents Association will host a free Christmas Fair at the hotel on Sunday November 24th from 12 noon to 4pm.