GOOD Friday was once a day of austerity, penance, a ‘Black Fast’. In medieval times, nothing was eaten until midday and even then it was only three mouthfuls of bread, and three sips of water, before sitting in silence until 3pm when Christ died on the cross.

By the 1930s, droves of adults and children spent Good Friday searching for shellfish, which were believed to promote good health.

They could be gathered along the shore rather than taking out a fishing boat on a day when the sea ‘craved dead bodies’.

A Ballydehob schoolboy recorded in 1937: ‘On Good Friday those who live by the sea go to the strand for mussels.’

Locals remember mussel-hunting on Good Friday through to the early-1990s.

On the pretext of ‘dropping off’ a bucket of mussels, the returning squad might slyly enter a closed pub (by the back door) and enjoy a few pints with the curtains drawn.

These days, families are more likely to venture on Easter Bunny egghunts.

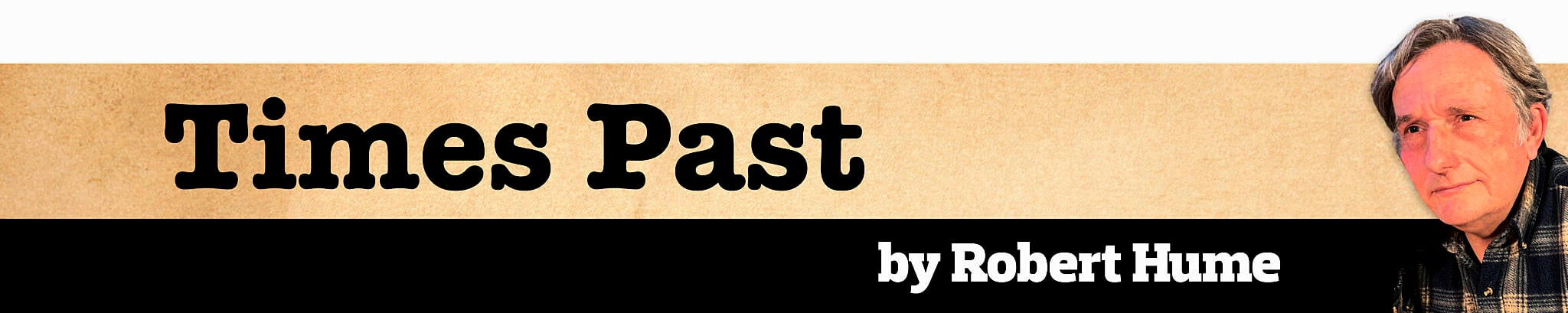

An ad from the The Southern Star in 1933, advising an appropriate diet for adults.

An ad from the The Southern Star in 1933, advising an appropriate diet for adults.Delighted they’d soon be selling meat again as Lent neared its end, butchers organised ‘funeral’ processions on Easter Saturday, hanging a dead herring from a pike and marching through the streets with it, accompanied by musicians.

Herring was once the ‘favourite food for dinners’, remarked Cathal Ó Macháin, teacher at Maughanaclea School, Cousane, Bantry, in the 1930s; ‘the most widely consumed meat substitute during Lent’, confirms Cork County Libraries’ Kieran Wyse.

Hundreds of people who were fed up with eating fish could at last take revenge by ‘whipping’ the wretch with sticks.

Nathaniel Grogan’s 19th-century oil painting depicts one such procession in Cork. Having flung the herring into the River Lee, revellers would gleefully carry back a dead spring lamb, dressed in ribbons and flowers.

Denied eggs for the 40 days of Lent, everyone would begin their Easter Sunday with a breakfast feast of boiled eggs.

‘One turns to eggs during Easter time as naturally as a duck does to water’, quipped The Southern Star in 1909. Every farmhouse had been visited to collect eggs. This age-old custom, known as ‘doing the rounds”, got a generous response because ‘nobody should be without an egg at Easter’.

In recent years, St Senan’s Church, Cloghroe, has held an Easter Egg Mass, where children present the priest with eggs, which the St Vincent de Paul Society distributes to the poor.

Eggs laid on Good Friday were once marked with a cross in memory of Christ’s crucifixion, and laid aside for the binge.

The average Irishman could allegedly scoff six! One of these was traditionally a goose egg.

In 1938, Tomás Ó Colmáin from Glantane, Lombardstown, recalled boys at his school boasting for days how many they’d gorged – the one who’d eaten most being ‘looked up to as a hero’.

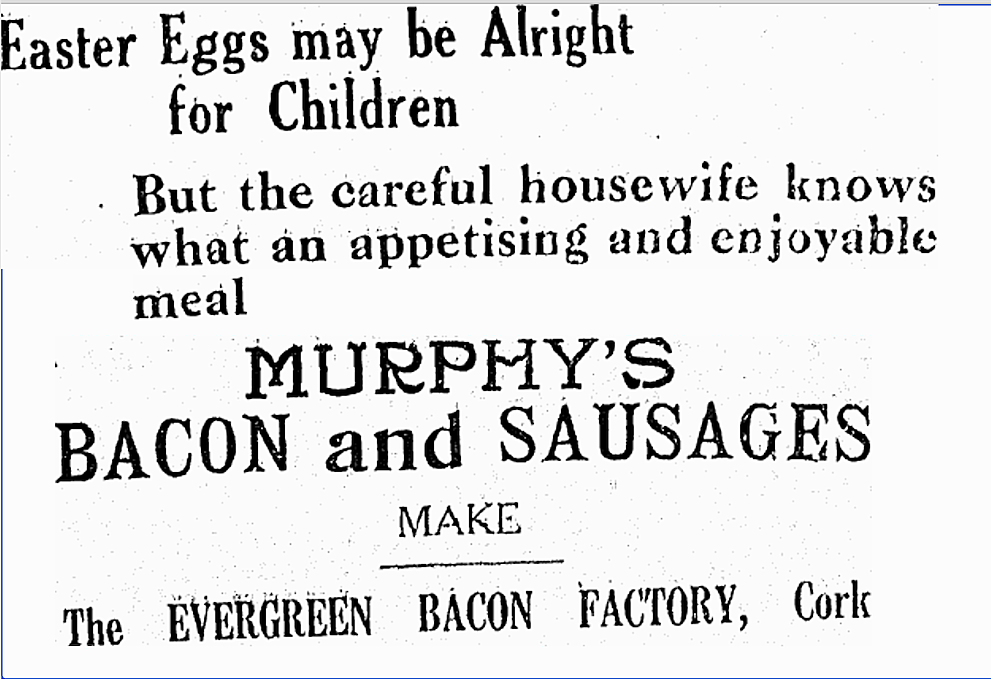

From The Skibbereen Eagle in 1915, a huge variety of fish advertised for Lent.

From The Skibbereen Eagle in 1915, a huge variety of fish advertised for Lent.Others frowned on such shenanigans. Noel Coakley, who grew up in Bantry, remembers several ‘non-complimentary’ references to excessive egg-eating in his primary school textbooks, including: ‘Three eggs a lout. Four eggs a thorough lout.’

Accompanying eggs came special bread, also marked with a cross, which was supposed to stay fresh for a year.

The custom survives in hot cross buns. Made with cinnamon and nutmeg, traditional versions represent the spices used to embalm Christ, although this Easter one West Cork supermarket chain is selling white chocolate and raspberry specimens!

Easter Sunday lunch was second in importance only to Christmas Day lunch, and meat was essential: it’s ‘a great embarrassment to be without meat on Easter Sunday’, goes an old saying. Lamb was a favourite, and featured in Easter hampers but corned beef and boiled bacon were equally acceptable.

Finally, sweets galore, in any form! Simnel cake, a rich fruit concoction with toasted marzipan on the top and sides, remains a traditional treat.

On Easter Sunday afternoon, dancing (forbidden during Lent) also returned, and ‘cake dances’ were organised throughout Ireland.

These medieval ‘dance offs’ were held outside, accompanied by a piper.

The couple that exerted most effort, or kept going the longest, ‘took the cake’ – usually a barmbrack – placed on an imposing piece of Irish linen.

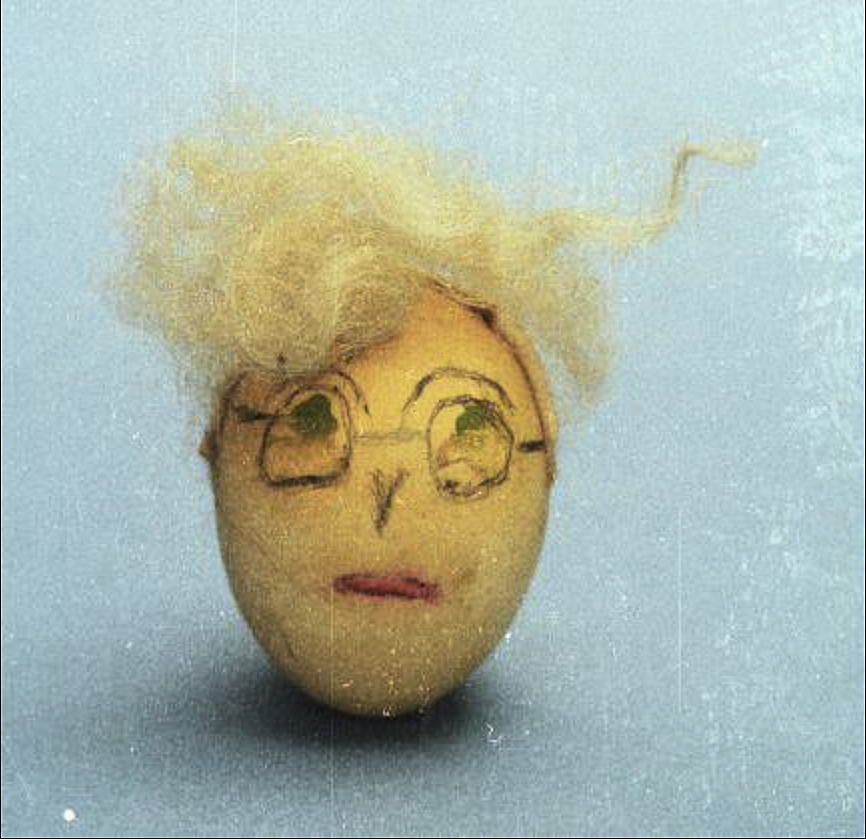

Some mothers boiled eggs with onion skins to give them an attractive colour, or drew faces on the shells for their children .

Some mothers boiled eggs with onion skins to give them an attractive colour, or drew faces on the shells for their children .(National Museum of Ireland, Country Life)

Costly ‘artificial’ Easter eggs had arrived in shops by Edwardian times: ‘There is scarcely a limit to the expense one may go to in buying such presents’, reported The Southern Star, on April 14th 1906.

They were strictly for children: ‘Nobody gives us – poor grown-ups – any Easter eggs’, complained a Star columnist in 1937: ‘We have to be satisfied with “common or garden” hen’s eggs’. As chocolate was ‘a once a week treat’ for children, even in the 1970s, an Easter egg ‘really meant something!’, says Terri Kearney, Skibbereen Heritage Centre. Retired Southern Star editor Con Downing recalls the ‘splurge of chocolate’ after fasting during Lent when he was young.

Noel Coakley would begin eating sweets ‘immediately after the noon Angelus bell ceased tolling’ on Holy Saturday: ‘These were the most delicious tasting sweets of the year!’