From the humble scythe and horse-drawn plough, to the diesel tractor and 775 horsepower combine harvester, farming machinery has radically changed over the years in West Cork, but locals haven’t always welcomed the ‘improvements’

BY ROBERT HUME

As spring beckons once again, life is beginning to return to our fields and meadows. But the techniques used to cultivate them have changed beyond recognition. Among the farming implements auctioned in 1924 by W.G. Wood & Sons in Drimoleague, was an ‘excellent’ swing plough, a zigzag harrow, a chaff cutter and a horse hay rake (The Southern Star 5 Apr. 1924, p.8).

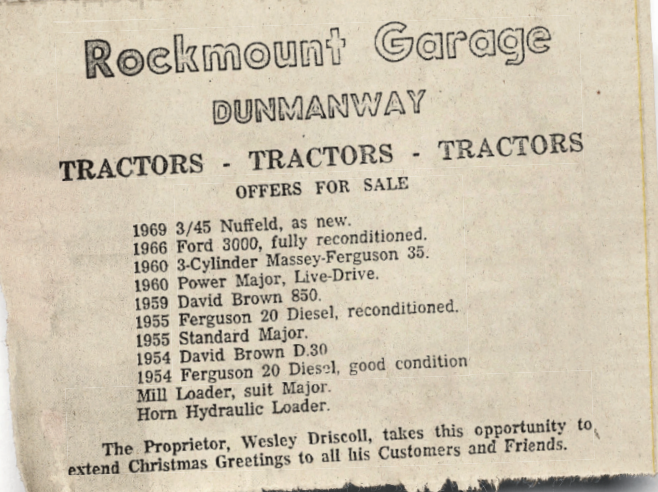

Tons of tractors on offer in Dunmanway, 1970 ( The Southern Star, 5 Dec. 1970, p.11).

Tons of tractors on offer in Dunmanway, 1970 ( The Southern Star, 5 Dec. 1970, p.11).

Today, in contrast, our farm machinery specialists advertise 50-horsepower tractors and 24-rotor power harrows, 1,000-litre sprayers and 15-ton slurry tankers.

Yet the work to be done, the never-ending 14-hour day, seven-day week, still endures.

The agricultural year kicks off in early March with ploughing, for the earth needs to be turned over and weeds buried before the seeds are sown.

Traditionally, It was work for two horses and two men. Children were once used to scare off the rooks by walking up and down banging clapperboards together – otherwise one seed in four would be lost.

Two horses pulling a spring harrow in Muckross. (Farm life in Ireland during the 1930s – Preserving the past)

Two horses pulling a spring harrow in Muckross. (Farm life in Ireland during the 1930s – Preserving the past)

In April and May potato ridges are built. It is ‘an exact science’, wrote Flor Crowley (West Cork Long Ago, 1979). Each ridge has to be ‘in a dead straight line’, with six sods to each ridge – three in each direction – and a furrow of eighteen inches width between every two ridges.

When the weather settles in June and July, haymaking begins, while September ushers in the reaping of corn and the bundling it into sheaths.

Although the tasks have barely changed, the tools most certainly have. In medieval times, corn was cut using scythes, which needed constant sharpening. Seed was once scattered by hand until a horse-drawn sower was available. To own a hay turner would make you the envy of your neighbours!

Some of the new machinery – such as Doyle’s digging and sowing plough, and Pierce of Wexford’s turnip sower – was manufactured in Ireland, and many items were shared with neighbouring farmers.

Horse-drawn steel bar plough, R Hornsby and Sons Ltd, 1876. (National Trust)

Horse-drawn steel bar plough, R Hornsby and Sons Ltd, 1876. (National Trust)

A huge boost in productivity came about with the introduction of the tractor. A Fordson tractor was built in Cork as early as 1919, although tractors pulling ploughs, rollers and reapers were not a common sight in West Cork until the 1930s, when the state-of-the-art reaper binder could farm an acre in an hour.

Fordson tractor in Cork, 1919. (Photo: Cork library)

Fordson tractor in Cork, 1919. (Photo: Cork library)

Every autumn witnessed the arrival of a tractor pulling a threshing mill. Locals greeted the machine – the hum from which could be heard three miles away – with a mixture of excitement and dread, for it spelt weeks of hard work for up to a dozen men. Its departure was celebrated with apple tart and honey cake, music and dancing.

The threshing mill reigned supreme until the 1960s, when the combine harvester made its appearance. One farmer in Belgooly told The Southern Star that six or seven acres could be cut, threshed and bagged ‘in no time’.

Early 1960’s Dania trailed combine. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

Early 1960’s Dania trailed combine. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

The combine harvester proved so popular that, in 1960, Hurley’s in Dunmanway urged farmers to ‘book early and avoid disappointment’. Many young men hoped they would never see the old threshing mill again. These days, power harrows, pneumatic fetiliser distributors, hydraulic folding harrows, and fully automatic potato planters are all on the market.

But some of this new machinery has met considerable opposition over the years.

One concern was the redundancies it caused. Farm labourers are ‘deprived of employment in the harvesting season’, declared The Southern Star (25 Aug.1956).

Many farmers in West Cork were deeply sceptical towards anything new. It took years before the new reaper and binder machine succeeded in ousting the trusty old mowing machine; while using a potato-sprayer was scorned as ‘flying in the face of the Lord’.

1950’s Massey Harrris reaper and binder. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

1950’s Massey Harrris reaper and binder. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

Others complained that the new technology (some of which was Russian) was not as robust as the old, or that it was suitable for USA and Canada but would not work in the wetter conditions of West Cork, an area of mixed farming and dairy. There were also practical problems: 11-foot wide combine harvesters were too wide to get through farm gates without damaging pillars.

Some machines are potentially lethal. Fingers were severed in threshing machines, hands got crushed in combine harvesters.

Last year in West Cork, a massive tractor carrying a wide load collided with a motorcycle while speeding along a road barely wide enough for two cars to pass.

The revolution in farming methods has undoubtedly saved farmers time and brought them vastly increased yields. But it has also caused unemployment because it only takes one individual to operate many of today’s machines.

Titan 10-20 tractor and Ransomes 1915 3F plough. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

Titan 10-20 tractor and Ransomes 1915 3F plough. (Photo: Peter O'Brien)

It has also reduced the number of social activities, particularly at harvest time. The sharing and companionship characterizing the older ways has also disappeared.

A recent study, carried out before Covid (The Great West Cork Farming Survey, 2018) reported that fifty-one per cent of farmers today – particularly the older ones – miss the social interactions of the past, and ‘feel alone’ in their work.