This week's Spirit of Mother Jones festival in Cork city will honour a man who introduced homes for labourers, known as the ‘Sheehan cottage’ and was also once editor of this very newspaper

WHILE soaring rents, a lack of Council accommodation and dozens of tents on Dublin’s canal banks all testify to today’s chronic housing crisis, a century or so ago, one Corkman believed he had the answer to a similar situation.

Daniel Desmond (‘DD’) Sheehan was a schoolteacher, politician, labour activist, barrister, soldier – and even a journalist!

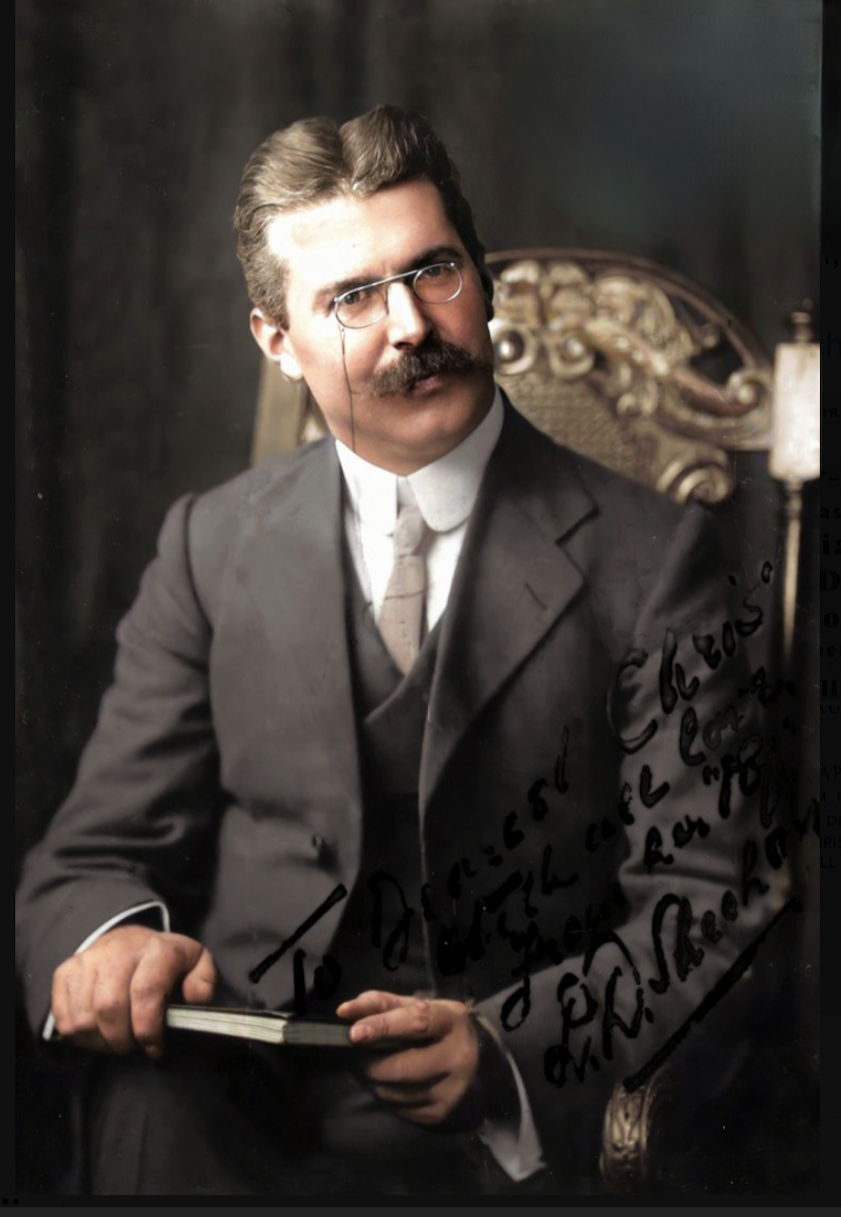

A portrait of DD Sheehan circa 1910 from Irish Family Detective.

A portrait of DD Sheehan circa 1910 from Irish Family Detective.

Born in 1873 into a family of Fenian tenant farmers near Kanturk, DD Sheehan was just seven years old when his family was evicted.

In his book, Ireland since Parnell (1921), he wrote how, during a brief spell as a schoolteacher, he witnessed the ragged poverty of labourers’ children, and this convinced him to take action.

By 1890, he had turned to journalism, reporting for the Kerry Sentinel and the Cork Daily Herald. As secretary of the Kanturk trade and labour council, he campaigned for agricultural labourers, and niftily reported meetings in his newspapers.

Following his marriage in 1894 to Mary O’Connor of Tralee, with whom he had five sons and five daughters, DD joined the Glasgow Observer, then became editor of the Catholic News in Preston, Lancashire. Four years later, he returned to Ireland, where he worked for the Cork Constitution, before serving as editor of The Southern Star (1899-1901).

During this time, he threw himself into organising the Irish Land and Labour Association, and became its president. By 1900 there were 100 branches, mostly in Cork, Tipperary, and Limerick. With fellow land reformist William O’Brien, he founded the All-for-Ireland League, which sought the gradual implementation of Home Rule.

Most working men now had the right to vote, and this helped secure his election as MP for Mid-Cork in 1901. At just 28, he was the youngest Irish MP, and the first Irish Labour MP.

DD’s greatest achievement was the passing of the Labourers’ Act (1906) for the construction of workers’ cottages. His study of law at UCC (1908-9), and his experience as a barrister on the Munster circuit, helped him with legal technicalities, and sharpened his oratorical skills, although intense periods of public speaking led to his collapse and drinking bouts.

During WWI, he organised recruiting campaigns among the farming communities of Cork, Limerick and Clare, was promoted to the rank of captain, and served at the Somme, contributing articles to the Daily Express from the trenches. Shellfire made him deaf, and after the war he had to give up as a barrister. He returned to journalism, becoming editor of the Stadium, a daily newspaper for sportsmen.

By this time, around 50,000 rural cottages had been built – throughout Munster and especially in Co Cork. At Tower, near Blarney, a ‘model village’ was constructed.

One of a number of ‘Sheehan cottages’, built in Tower near Blarney circa 1909.

One of a number of ‘Sheehan cottages’, built in Tower near Blarney circa 1909.

Each cottage cost about £200 to build: UK taxpayers met 36% of the expense, the rest was borrowed over a 70-year period at a modest 3.25% interest rate. If a case could be made that a cottage was needed, the local authority was obliged to acquire the land and build one.

The dwellings were built from concrete instead of traditional stone or mud, and had roofs of slate rather than thatch. To make them easily accessible, they were situated on the roadside, and came with a half-door – for ventilation against dampness. Each had a well, and a one-acre garden.

At a rent of one shilling per week, the cottages provided ‘a welfare state for the labourer’, says historian Jack Lane. Lane was born and grew up in a ‘Sheehan cottage’.

‘As in my case, there could be three generations and even up to 10 people per cottage’, he recalled.

The main issue in Irish life for centuries centred on ‘the confiscation and retention of land by a foreign power, and the attempts to reverse that process by the natives’, stated Lane. Tenant farmers had neither the resources nor capacity to remedy this situation until DD came along. His cottages transformed rural Ireland. They were ‘the Western world’s first large-scale public housing scheme’.

Daniel Desmond Sheehan died, aged 76, while visiting his daughter in London on November 28th 1948, and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. Since that time nobody has successfully addressed the housing problem. Yet it was solved in rural Ireland well over a century ago.

For his pioneering work, DD Sheehan deserves a lot more space than he’s received, says Ger O’Mahony, the Spirit of Mother Jones Festival co-ordinator. ‘We want people to hear more of this story, and next week they can.’

Jack Lane will tell of DD Sheehan’s efforts to house rural labourers at The Spirit of Mother Jones Festival 2024, at 2.15pm on Saturday 27th July at the Maldron Hotel in Shandon.

The festival honours Mary Harris, who was born in Cork in July 1837 and emigratedto Canada during the Great Famine. After marriage to George Jones, a union moulder, in 1861, tragedy stuck when a yellow fever epidemic took the lives of her husband and four young children, in 1867. She became a tough and feared union organiser and, having led many strikes for better play and conditions, she was known throughout the US as ‘Mother Jones’ and is remembered fondly to this day.

Jack Lane’s lecture is one of about 30 events in and around Shandon, from Thursday 25th July to Saturday 27th. For more, see www.motherjonescork.com.