KIERAN DOYLE takes a look at some of our war memorials – or the lack thereof – around Co Cork

DESPITE the conservative estimates of 35,000 Irishmen who died in the Great War, compared to approximately 2,400 deaths in the WOI, it may surprise people that there were only two Great War monuments on display to all the general public during the 1920s: the Cork city memorial on the South Mall and the one in Kinsale at Land’s End.

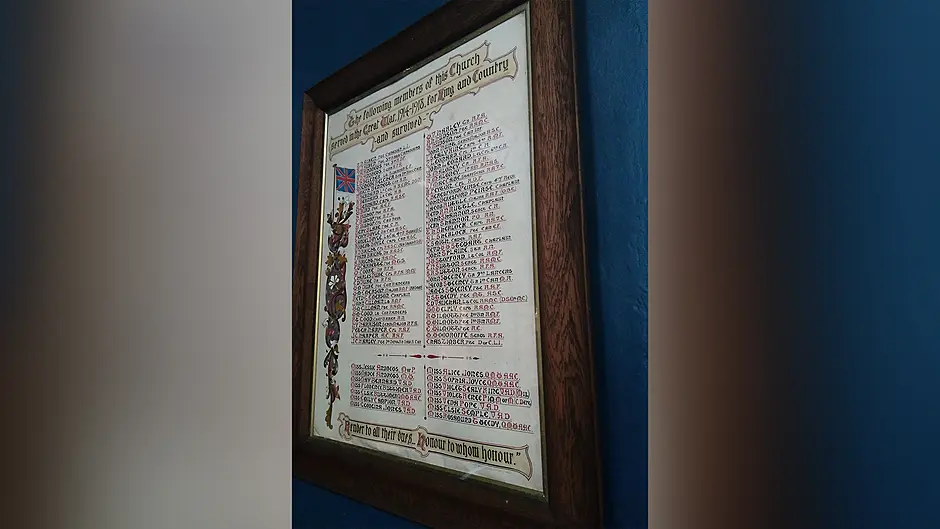

There were more localised Great War memorials displayed, but only public to one side of society – Irish Protestants. They are indoors, away from discerning eyes that felt the Great War was another relic of Britishness and from a society that mainly believed that commemoration should only have a green tint.

One of the most significant of the Great War memorials of this period is the one found inside the magnificent St Peter’s Church in Bandon. Its significance is due to a number of factors.

Firstly, it commemorates not the dead, but all those who ‘fought and survived’. Secondly, it is the only Great War monument that names female participants. There are 14 women emblazoned on the memorial, including three sets of sisters.

There are a curious set of acronyms connected to each name. Four women, Elise Buttimer, Sophia Joyce, Rosamund Tweedy and Alice Jones have the initials QMWAAC (which stands for The Queen Mary Woman’s Army Auxiliary Corp), after their names. Founded in 1917, as the WAAC, it received royal patronage from Queen Mary for outstanding work during the spring offensive in 1918 and the initials ‘QW’ were added in recognition of this.

Much of their work centred around taking the place and jobs of men who served abroad. Not only did this aid the war effort, it would shape attitudes towards the spectrum of work that women could do successfully.

Their work also included administration and store workers on a more military level, in an era where women were not part of the soldiery.

It’s interesting to note the different strata of society that volunteered for this – Sophia Joyce was a draper in Bandon, whereas Rosamund Tweedy was married to an RIC district inspector.

Other women are on the memorial, such as Violet Sealy King, May Bernard, Veda Pope, to name but three, had the initials VAD after their names. This was an acronym for the Voluntary Aid Detachment. Their job was to provide meals for soldiers at train stations and nurse those in transition.

The British Red Cross employed 2,812 women from this corps and 128 died in the service of their duty. Again, the women are from different classes of society.

One of the women, Emily Campion was daughter of a railway station master, whereas May Bernard was of the landed gentry and related to Lord Bernard.

Violet Sealy King’s husband was part of the Royal Flying Corps. One woman, Jessica Andrews, had the initials MP after her name which suggested she had a role in the Ministry of Pensions. Her sister Madge and another women Violet Renne had MM after their names, representing their attachment to the Ministry of Munitions.

The symbolism of such a monument speaks just as loud as the words.

The Union Jack is emblazoned on the bottom and the words ‘for king and country’ pertain to a very different tradition as opposed to the War of Independence monuments. While the Church of Ireland has a long tradition of commemorating people of their community within their churches, the 1920s was not an era where more open public recognition may have been welcomed in a society still smouldering from British acts of attrition. The decade-long vandalism of the Cork City Great War memorial and incursions upon the Kinsale war monument to the point of its irrelevance, perhaps proved that the general decision to commemorate their war dead publicly, but inside their churches, was the right one at the time.