After last week’s exclusive report on nitrates in Lough Hyne, Eimear O’Dwyer delves deeper into the research undertaken by the two scientists who have studied the marine nature reserve for three decade

MARINE researchers at Lough Hyne Dr Colin Little and his wife Penny Stirling have been voluntarily coming to the lake for more than 30 years to monitor the marine life.

The couple, who are now in their 80s, have just carried out their last research trip to Lough Hyne.

Colin first came to the lake in 1979 when he was working at the University of Bristol as a lecturer in marine biology, and the marine life at Lough Hyne piqued his interest. He came back to the UK and told Penny about how wonderful everything was there.

The following year Penny, who had no background in marine biology, decided she would join him on his trip to the lake.

‘I worked in the medical school as an electron microscopist. I had nothing to do with marine biology,’ she said. ‘But I wasn’t going to miss out on the fun.’

And every year since they have been coming back to the lake to carry out self-funded research. They have been shore biologists from the beginning – looking at the creatures on the shore and carrying out experiments with them.

It was in 1990 that the pair were inspired to carry out monitoring surveys of the lake, because they found out at a conference that year that there was research on the marine life at the lake, dating back to 1955.

‘At the conference, one of the things that showed up was the fact that there had been some monitoring, way back in 1955. So we did the monitoring in 1990 and in fact what we’ve been doing this year is to repeat the exact the same thing in exactly the same way,’ Colin explained.

Colin and Penny have been surveying the sites that were first examined by Louis Renouf, 100 years ago, in 1923. They manually record the marine life with pencils and paper, in the exact same way that monitoring surveys in the 1950s would have been done – so that they can be compared accurately.

The only change they have made to their research methods in the past few years is to record their findings on waterproof paper. Penny joked that this is a ‘major stride forward’ for them.

‘So at least the marks you make on the paper will stay put ,unlike if you put it onto ordinary paper and wipe a wet, salty arm over it and it all vanishes,’ she said. ‘In 43 years that is our major advancement!’

And now the pair have amassed more than 30 years of research on the lake.

‘We’ll publish the data sets from this year and last year and that will be there as a record so that in another 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 years or whatever – if other people do the same kind of monitoring, they’ll be able to make comparisons,’ said Colin. ‘The long term data set is the interesting bit, because we can compare back to 1955 and things really are different.’

‘There were masses of purple urchins then, there were masses of topshells in the shallow water, there were masses of a green seaweed called codium and if you look around now it’s completely different. The interesting thing is that if somebody came along now and looked at the lough, they’d think that what’s there is just normal, but it’s not normal compared to 50 years ago,’ he said.

On the issue of climate change, Colin said there isn’t much evidence of it having an adverse effect. ‘We think that the water temperature hasn’t really gone up much, but the air temperature seems to be warmer now than it used to be.’

And some species are not too enamoured by the warmer air temperatures. When the tide goes out, and they are exposed to sunshine or warmer air for longer periods of time, they can get quite hot on the rocks, Penny explained.

‘There is one barnacle that has diminished to almost nothing – that’s a cold water barnacle and now it’s hardly there and that’s probably due to increasing temperature of some sort,’ said Colin.

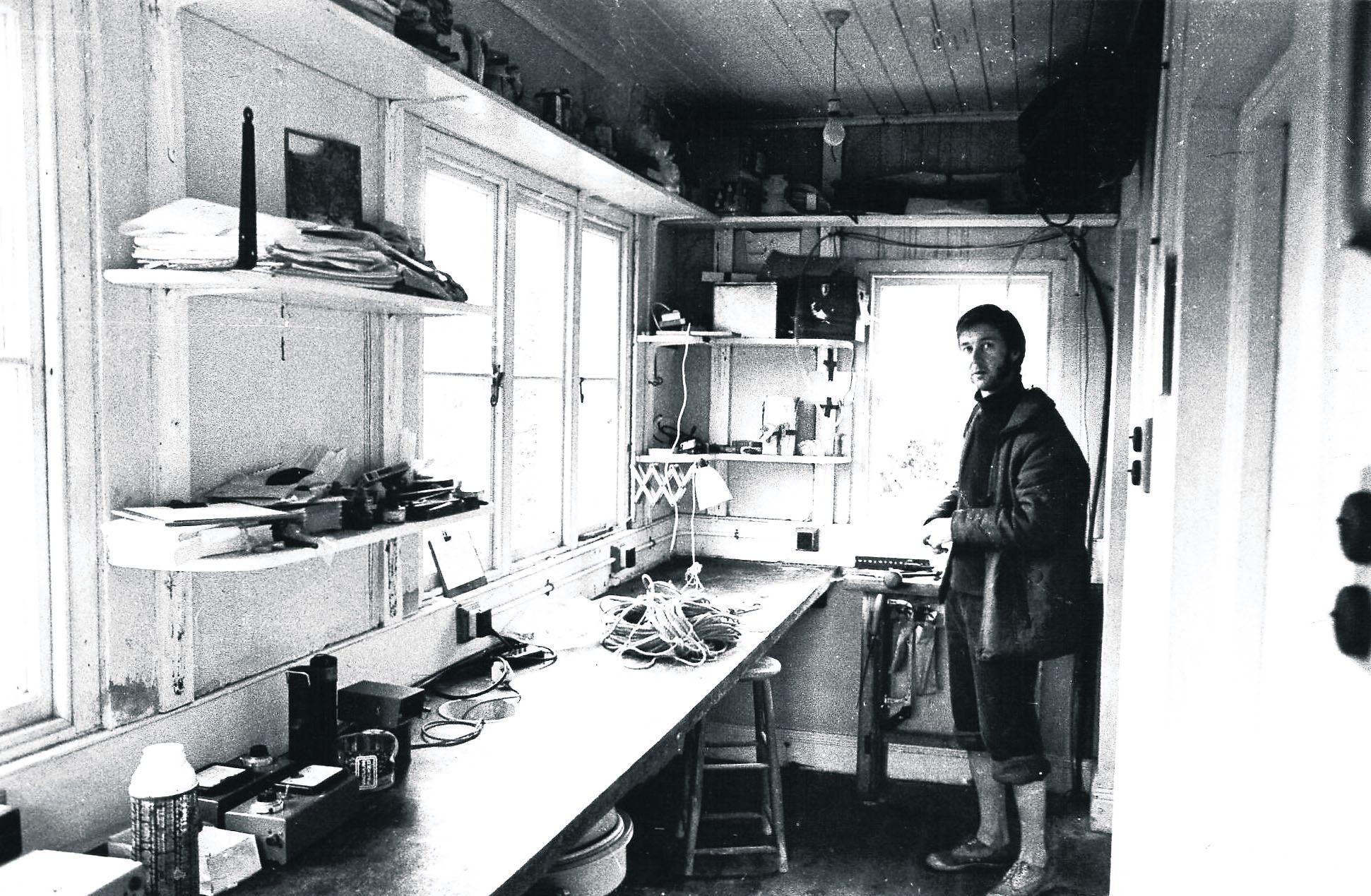

Colin Little first came to Lough Hyne in 1979 when he was working at the University of Bristol.

Colin Little first came to Lough Hyne in 1979 when he was working at the University of Bristol.

Nitrogen, however, is the more prevalent issue in Lough Hyne. The researchers believe that agricultural run-off along the south coast of Ireland comes into the sea, and then flows into the lake – causing a build-up of nutrients in the water. The nutrients cause a build-up of algae, Colin explained. And this clogs everything up, and when it dies, it takes away all the oxygen.

‘There is a lot of healthy sealife, but it’s usually on top of the rocks, not underneath them – so a lot of the bottom of the rocks are anoxic (lacking oxygen),’ he said.

This oxygen deprivation has now caused marine life under the rocks to die. Colin and Penny used to see a lot more sponges, sea mats and starfish and top shells – but now they hardly see any at all.

Colin and Penny’s research has been fundamental for the lake, and for any future research that is carried out at Lough Hyne. Now that they have finished their last research trip to the lake, they have returned to their

home in Wilcher in the UK to retire.

And they will take with them their fond memories of Lough Hyne. ‘We’ve met a lot of local people over the time and everybody’s been so kind,’ Penny said.

On coming back to the lake for a visit in the future, Penny said: ‘We don’t know, when you get to our age, you don’t buy green bananas!’