Robert Hume recalls an accident to a passenger train travelling from Cork city to Dunmanway in 1869, and wonders whether negligence, or possibly sabotage, could have been to blame

Robert Hume recalls an accident to a passenger train travelling from Cork city to Dunmanway in 1869, and wonders whether negligence, or possibly sabotage, could have been to blame

On Thursday May 20th, 1869, the three o’clock train from Albert Quay in Cork was rattling across the Chetwynd Viaduct, ready to negotiate the long tunnel at Gogginshill, on its way to Dunmanway.

There was no scheduled time of arrival – often the case with the early railways – but an hour had elapsed, and over half its journey was complete.

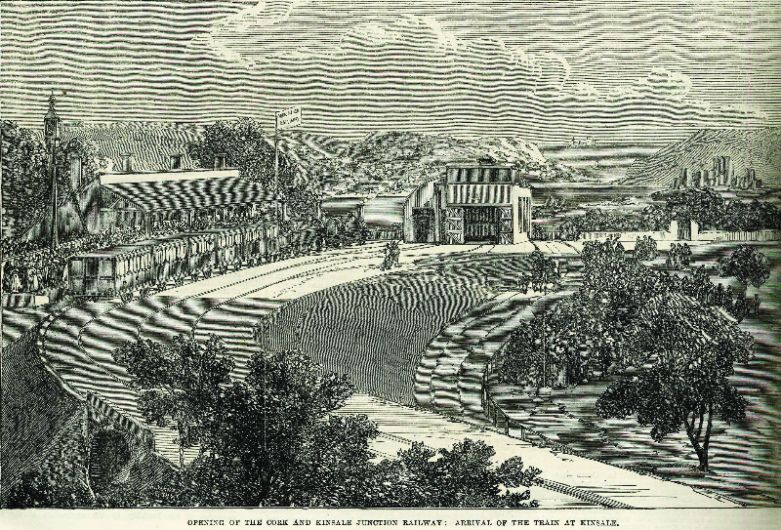

Near Crossbarry, six miles before Bandon, lay an intersection, where trains operated by the Cork and Kinsale Junction Company turned down to Kinsale.

But West Cork Company trains, like this one, continued towards Bandon and beyond. As the company had run out of funds to build the line any further, at Dunmanway the train would be met by horse-drawn omnibuses belonging to the Queen’s Old Castle Company, each capable of carrying 25 passengers, to Skibbereen or Bantry.

On the ‘three o’clock’, passengers sat back in their upholstered seats in carriages resembling three stagecoaches squashed into one. They were delighted to be travelling in a ‘through train’ that had ‘running powers’ over the Cork and Bandon line, and did not involve the inconvenience of changing train at Bandon.

Down below them, the signalman would be ready to use a lever by the side of the track to set the points, enabling their little steam locomotive to climb towards Bandon’s West Cork station, and finish its journey 18 miles down the line at Dunmanway.

But that afternoon he either neglected his duty, or botched the job.

Instead the train started to run along a stretch of branch line. This track sloped downwards and ended abruptly with a revolving table used to turn steam locomotives around, so they did not have to make their return journey in reverse.

Baffled, the driver immediately applied the brakes. But he could not bring the train to a stop in time.

The locomotive shot across the turntable and ploughed into the ground.

The severity of the braking broke or bent several carriage buffers, which being rigid in those days rather than spring-loaded, did little to absorb the shock.

Passengers were catapulted out of their seats, their heads ‘dashed with some force against the opposing partitions’, as one traveller wrote in a letter to the Cork Examiner, five days later.

Many received bruises and scratches, and one lady was feared ‘rather seriously hurt’.

Somehow or other the carriages managed to stay on the rails. Today’s ‘customers’, as they are known, would have been offered trauma counselling.

But on that spring afternoon in 1869, passengers – who had bought tickets costing up to three times those offered by the stagecoach – had to clamber down the steps unaided, with all their luggage, only to be left stranded on Bandon Station until 9.30pm, when the night train took them to Dunmanway.

Reflecting on the accident, a correspondent for the West Cork & Carbery Eagle concluded: ‘It is quite miraculous that it was not attended, with loss of life and casualties of a serious nature.’

Passengers’ lives had been endangered by, at best, ‘culpable neglect’, at worst by gross – possibly wilful – ‘mismanagement’.

Their train had been diverted at speed into a siding; and they were detained for five-and-a-half hours ‘to suit the convenience, and spare the pockets of railway officials and shareholders.’

No satisfactory explanation could be obtained about the cause of the accident, ‘there being no responsible person in charge at the Railway Station’.

Back in 1866, when the local railway companies had agreed to share their track, they pledged to work together ‘harmoniously’, to ‘accommodate’ and ‘protect’ one another’s traffic.

In practice, relations quickly turned sour. The Cork and Bandon Railway was not interested in, and refused to be accountable for, trains run by the West Cork Railway Company, for which it received no remuneration.

The Kerry Evening Post complained about the CBR’s ‘obstructive policy’ towards ‘through’ trains, and Lord Bandon condemned the line as ‘the worst managed railway in Ireland’.

Eventually the West Cork Railway built a completely new station at Rice’s Road.

According to the Eagle, such poor management resulted in railway accidents ‘constantly occurring’ and insurance companies were keen to cash in on passengers’ fears of travelling on the newfangled trains. After all, you might never reach your destination.