The burning of Skibbereen’s Workhouse, 100 years ago this month, was one of a number of reprisals against British forces in West Cork during that summer, writes Robert Hume

--

AT about 1am on Thursday June 23rd 1921, three weeks before a truce in the War of Independence with Britain, over 300 armed men surrounded Skibbereen Union Workhouse.

Having woken up the Master, they demanded he bring out the inmates and patients.

The most aged and infirm of these – ‘idiots’ and those ‘unable to help themselves’ – were led by the Sisters of Mercy to the fever sheds, where they huddled together, terrified.

The Southern Star described the raiders behaving in ‘a cool, systematic manner’ as they set the building alight.

By morning, little remained: the flames had eaten up everything combustible in their path. ‘The workhouse is a mass of smouldering ruins,’ reported the Cork County Eagle. Both the male and female sections of the house, the chapel, the hospital, the officers’ quarters, and the boardroom lay ‘completely gutted’.

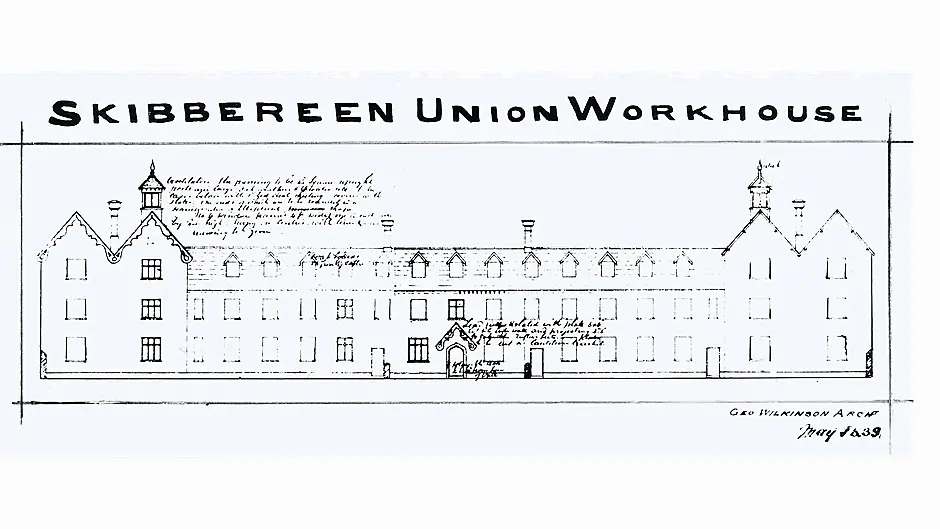

Skibbereen Workhouse had been one of the largest in the county, and was built in 1841 where the Community Hospital now stands, a mile north of the town, to house over 800 paupers drawn from a large rural catchment area of 369 square miles. Conditions inside had been tough: men, women and children split up, and made to exist on bread, cheese and gruel.

Women had to cook, sew, wash clothes and mend ships’ ropes, while men broke stones for the roads and crushed bones to make fertiliser.

The sculpture, above, in the grounds of Skibbereen Community Hospital honouring the 110 Skibbereen girls who left the workhouse in 1848 for Australia.

The sculpture, above, in the grounds of Skibbereen Community Hospital honouring the 110 Skibbereen girls who left the workhouse in 1848 for Australia.Only the destitute would have ventured inside its high, forbidding walls.

‘No man able to struggle on outside seeks the hospitality of the house,’ asserted the Eagle.

The situation in West Cork had been so desperate in December 1848, at the height of the Famine, that 2,800 paupers lay crowded inside, and fever victims slept six to a bed.

Numbers would have been higher still if 110 teenage girls from Skibbereen, each carrying a bowl and spoon, had not been removed earlier that year and transported to Australia where they became known as ‘breeders’. A plaque now stands in the grounds of the current Community Hospital, in their memory.

But the number of inmates on the night of the fire in 1921 was far fewer, between 125 and 130.

According to the Star, the raiders helped the inmates reach places of safety.

But the Eagle was sceptical: ‘Many are absolutely friendless and now do not know where to turn … gaunt figures … pitiable beyond words to express … scattered as useless human chaff to the winds of chance and the slender resources of other Unions.’

For them and hundreds of other hungry folk, the Skibbereen Workhouse had been a vital ‘temporary refuge’, a ‘dry dock’, where they could anchor for a few days, weeks or months, in times of need.

Why had it happened? Ratepayers had long since found the upkeep of workhouses expensive and wanted to abolish them, but that didn’t explain why Skibbereen Workhouse had been torched that particular night, argued the Star.

Rather, it described the burning as ‘a military act’, the latest in a series of reprisals against Britain for blowing up, or burning down, Republican homes and business premises.

The police stations at Timoleague, Leap and Rosscarbery had already been torched to prevent them accommodating British forces.

So had ‘Big Houses’, including the 60-roomed Kilbrittain Castle, Dunboy Castle at the edge of Bantry Bay, and Warren’s Court near Macroom, a noble residence blessed with three lakes, and housing a church organ in its vestibule.

Also in the line of fire were Protestant farmers, magistrates (or their courthouses), deputy lieutenants and ‘nominally retired’ British military and naval officers – including Colonel William F Spaight at Union Hall and Brigadier General FWJ Caulfield at Innishannon House – who might happily have agreed to billet British soldiers.

Now it was the turn of workhouses to be destroyed before they, too, became bases for Crown forces.

The night before Skibbereen Workhouse had been targeted, most of Bandon Workhouse had been razed to the ground, and the inmates forced into the dispensary.

A month earlier, Macroom Workhouse had also been torched. A similar fate awaited Dunmanway Workhouse in the summer of 1922. A Poor Law Union meeting on June 25th confirmed that most of Skibbereen Workhouse did indeed ‘lay in ruins’, and its hospital wards ‘rendered useless’.

What ‘a sad condition of affairs to have the poor, and the sick poor especially, deprived of their only earthly comfort’, commented chairman John Holland.

The perpetrators, all young Irishmen, not merely displayed ‘a shameless indifference’ to their fellow-beings, accused the Eagle, but also committed a ‘repulsive’ act of sacrilege, never witnessed before in Ireland, by desecrating a Catholic chapel. Compensation to the tune of £10,000 would be sought for ‘malicious damages’.

Foster parents were urgently needed for the workhouse children, and before the rains began and winter set in, the damaged kitchen roof needed mending, a temporary operating room and surgery fitted up, and a fresh stock of medicines obtained.

One of the 27 Poor Law Guardians, Mr Thomas Horrigan, asked that sick inmates be transferred somewhere else while the repairs took place. But nothing was done to move them, and not a single repair was carried out.

By July 2nd, 52 paupers had been compulsorily discharged, whether or not they knew people who were willing to look after them.

With no other public provision available for the poor, they were left to their own devices.

‘It is pitiful to see some of them begging around the town,’ commented Mr William Walsh, another Guardian.

‘In the name of the God of Pity, who gave the order to empty, of its tragic human wrecks, what remains of the Skibbereen Poorhouse?’ demanded the Eagle. ‘Surely not the Guardians of the Poor, this would make their title a mockery?’

‘In every street in Skibbereen,’ lamented the paper, ‘you can see squalid, hopeless, unaccustomed figures drift aimlessly up and down.’ They were like owls, ‘brought forcibly out of the familiar twilight in which they feel at home, and flung into the face of the noon-day sun …’

This act, it warned, may turn out to be ‘the crime of which future generations of Skibbereen men will be most ashamed.’

As winter set in, local people were forced to accept that the Skibbereen Workhouse was a thing of the past, and there were no proposals to rebuild it. When the poor law system throughout Ireland was gradually overhauled in the early 1920s, workhouses for the poor and elderly did not vanish – they were rebranded as ‘county homes’.

But in the summer of 1921, many a ratepayer viewed the apparent disappearance of Skibbereen Workhouse with ‘a complacent calm’; as if in the fire that had eaten up its rafters and roof, pauperism, too, had been annihilated. Oh, if that were so simple.