Recent TV documentaries have made much of the fact that there hadn’t been a murder in West Cork for over 70 years until Sophie Toscan du Plantier’s death. But in late Victorian times, the Southern Star reported killings on a disturbingly regular basis. Robert Hume recounts one

In broad daylight on market day, Saturday February 24th 1900, as war raged in South Africa, and Queen Victoria’s health was fading, a 48-year-old man lay dead on the floor of his office in Bantry.

Local doctor Thomas Popham found bullet wounds in the man’s right arm, chest and head. A ledger, open on his desk, contained an incomplete entry; on another book rested a cheque with the ink still wet.

The body was identified as that of William Simms Bird, JP, magistrate and land agent, who had an office in Barrack Street above Warner’s shop.

Shopworker Fanny Dukelow heard a ‘stamping of feet’ at about 2.25pm that day, and a piece of mortar fell from the ceiling. Then another noise, ‘as if someone struck a door with a rod.’ Kitchen maid Sarah Beran described: ‘boxes falling’, while Bob Warner heard ‘two quick gunshots, maybe three.’

Popham was confident the wounds were not self-inflicted, but news spread that ‘Master Willie has shot himself.’ Others blamed the crime on his brother, Dr Robert George Bird.

Bantry police quickly arrested tenant farmer Michael Hegarty, who had visited Bird’s office shortly before he died, and owned a revolver. Besides, the last entry in Mr Bird’s ledger had his name on it.

Another visitor to town that day – Timothy Cadogan – was also in the frame. In October 1894, an ejectment order had been served on him for four years’ rent arrears on his farm at Cooleenlemane, and the following August possessions were removed from his cottage while he was out. Once back, he started throwing bottles and plates against the wall, demanding Mr Bird give him more time to pay, until he found work – or married a rich woman. According to Dr Bird, Cadogan had recently appeared at his brother’s office ‘very sullen and morose’, shouting: ‘You have done your worst. May the devil thank you, and you may be sorry for it.’

Arrested the morning after Mr Bird died, Cadogan admitted being in Bantry until about 6pm but said he spent the time in Hurst’s public house, and wandering around the shops to buy biscuits.

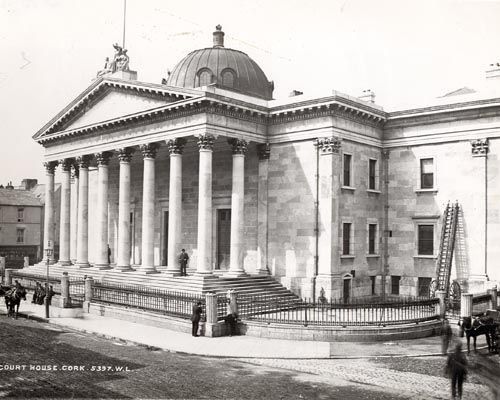

That very day he was charged. His trial began at the Cork County Courthouse on Wednesday July 18th, presided over by Mr Justice Kenny. The building was packed with spectators.

During the solicitor-general’s lengthy opening address, the defendant seemed composed and sometimes smiled. Under questioning, he claimed he left Coolmahon at about 11am on February 24th, and walked the six miles to Bantry to look for work. The prosecution were sceptical this was his reason for going.

An old man called William Levis claimed that soon after his eviction, Cadogan told him that in olden days he could have gathered a mob ‘to have satisfaction’ on Bird. But ‘we have another way of doing it’, he said, making a gesture as if pointing a gun.

The Sunday before Mr Bird died, Jeremiah McCarthy reckoned he saw Cadogan in the square, cap in hand and shouting, at a Land League meeting, where references were made to evictions on the White family estate at Glengarriff, where Cadogan had been a tenant and Bird a receiver of rents.

On the day of the incident, John O’Leary vouched that Cadogan was in Bird’s office, and the pair suddenly stopped talking when they heard him on the stairs. Mr Bird seemed angry.

Warner’s messenger boy, 19-year-old Walter Dennis, said he heard two shots from Mr Bird’s office above and saw a man come down onto the landing carrying a revolver in his right hand. That man was Cadogan. The court gasped.

However, beehive manufacturer James A Abbott used a model of the shop and office to demonstrate that it was impossible for someone standing at the shop door to see a person on the landing; and Mr McMullen, who had made a plan of the premises, reckoned the light was ‘very bad’ on the landing, making it difficult to recognise someone without going to the foot of the stairs.

Moreover, John Cronin claimed he stood opposite Mr Bird’s office for five minutes after the shots but nobody came out.

After spending a second night locked in Cork’s Imperial Hotel, the jury failed to agree upon a verdict, and the trial was postponed until winter.

When it resumed under Lord Chief Justice Peter O’Brien on December 10th, the man first arrested, Michael Hegarty, admitted attending a Land League meeting and owning a revolver but on the day of the killing it was at home. He denied exchanging angry words with Mr Bird, saying it was ‘ordinary talk’.

The trial was held in ‘Cork County Courthouse’. (Photo: The Lawrence Collection)

The trial was held in ‘Cork County Courthouse’. (Photo: The Lawrence Collection)

Attention shifted back to Timothy Cadogan.

After deliberating for 80 minutes, jury foreman Mr T Holland confirmed in a faltering voice that they found the prisoner guilty. He laid his head dejectedly on his hands.

The announcement caused hissing in the gallery.

Asked whether he had anything to say, Cadogan didn’t reply, and when told to stand he seemed astonished, dazed.

Putting on the ‘black cap’, O’Brien declared that on January 11th 1901 Cadogan would ‘be hanged by the neck until he was dead’.

Only while he was being dragged away was the prisoner’s voice heard. Turning towards the jury, his face darkened with anger as he pointed towards Dr Bird: ‘I hope I won’t be dead 12 months till I have avenged the doctor – the scoundrel, the cut-throat!’

Three days before the due date, public executioner James Billington arrived by mailboat from England with his son.

Resigned to his fate, Cadogan passed his final days reading the West Cork newspapers. But on the night of January 10th, he showed ‘considerable uneasiness’, and seizing one of his boots, tried to gash his throat with its iron tip.

At 6.45am, the next morning, he received Holy Communion before eating a breakfast of two eggs, bread and butter, and tea. Afterwards he left his cell and returned to the chapel to pray.

The death bell tolled as the procession trudged towards the scaffold, and the pinioning began, Billington being assisted by his son.

By a minute before 8am everything was ready. With ‘lightning rapidity’, Billington drew a white cap over Cadogan’s head, adjusted the noose and pulled the lever, opening the trap door beneath his feet. Seconds later, his lifeless body was swaying seven feet below. Instantaneous death, declared the prison surgeon.

A 200-strong crowd had assembled in the cold mist to see the black flag hoisted over the prison tower, confirming the sentence had been carried out.

It’s still unproved whether his fate was deserved.