The Civil War was a relatively brief conflict that lasted approximately eleven months but its impact has been felt for generations. West Cork witnessed extensive fighting, writes historian Alan McCarthy

LEAVING to one side the large shadows cast by figures like Michael Collins, Tom Barry and the Hales family, what was the Civil War in West Cork like for ordinary citizens and soldiers? Skibbereen had the bloody distinction of being the site of the last fatality of the War of Independence in West Cork when Constable Alexander Clarke was shot just before the Truce of July 1921.

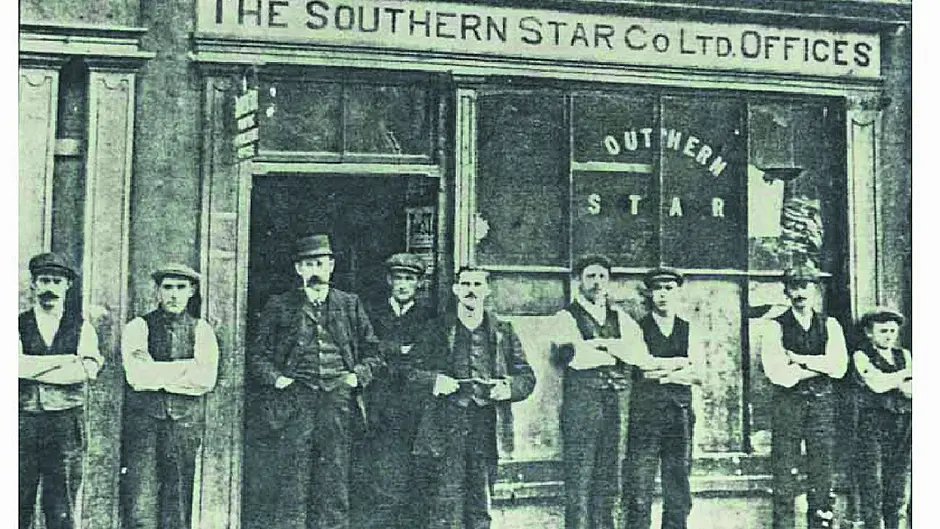

Nearly a year later, Skibbereen was the site of the first Civil War fatality in the county when anti-Treaty IRA section commander Patrick Francis McCarthy Jnr was shot on July 3rd. From Ballydehob, he succumbed to his wounds in Bandon hospital the following day. Prior to the gunfight in Skibbereen, Ted O’Sullivan recalled: ‘There was room for trouble.’ Fighting broke out on July 1st, with pro-Treatyites surrendering three days later. During the conflagrations in Skibbereen, Southern Star director Seán Buckley, along with Thomas Healy and James Duggan, tried to arrange a ceasefire.

Despite the conflict, civilian life in West Cork maintained a familiar hue – at a meeting of Skibbereen Rural District Council Peadar Ó hAnnracháin had a motion to ‘cut a rock and fence the road at Bauravilla on main road between Skibbereen and Drimoleague’ rejected. The cattle fair in Schull was said to be ‘the largest in some years’, though closer to the fighting in Skibbereen it was noted that there were delays in the construction of the new ball alley, ‘excusable owing to the existing conditions.’

At a meeting of Skibbereen Union, JB O’Driscoll stated that he ‘was glad to see that the Cork Harbour Board were doing something to try and stop the terrible conditions of things prevailing in the country at present.’

The Southern Star was, like its directors, at times somewhat muddled on where it exactly stood and exuded occasionally contradictory views. Reacting to the Cork Harbour Board conference, the paper carried the heading ‘Let There Be Peace,’ beneath which it editorialised that ‘Force will never satisfactorily settle the question on one side or the other’, and that people should work towards ‘reciprocal cooperation and good will.’ The very next piece, ‘A Lie Nailed’, challenged the official account of the deaths of anti-Treaty IRA members in Cushendell, concluding that ‘The cause that rests on such falsehoods is doomed to destruction.’ The anti-Treatyite re-occupation of Skibbereen in July brought about the closure of the Skibbereen Eagle, a former loyalist paper that supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The Eagle had fallen prey to several boycotts, raids and assaults on both its offices and staff during the War and Independence and the Truce.

Gone but not forgotten - the grave of Patrick McCarthy at Aughadown old graveyard. (Photo: Anne Minihane)

Gone but not forgotten - the grave of Patrick McCarthy at Aughadown old graveyard. (Photo: Anne Minihane)Newsagents had been discouraged from stocking the paper and advertisers discouraged from buying space in its columns. Its editor Patrick Sheehy told the Irish Grants Committee that people found in possession of the Eagle were liable to be punished. In the pages of the newspaper it was written at the time that ‘In consequence of conditions, arising from the present unsettled state of the country, the directors of the Eagle have decided to suspend its publication until further notice.’

West Cork men were also quite prominent elsewhere. Seán Lehane from Schull was sent to Donegal to assist First Northern Division in early 1922 and was subsequently tasked with revitalising Wexford.

Two columns of West Cork men were also heavily involved in the fighting in the pivotal south Limerick triangle of Kilmallock, Bruree and Bruff in August. This area was of huge strategic importance and the stubborn resistance of the anti-Treatyites was seen as a moral victory.

Nevertheless, the National Army continued to capture the main urban centres throughout the country.

One of the bloodiest parts of West Cork during the Civil War was Bantry and its environs, with a number of combatants from both sides being killed in or near Bantry town, as well as the villages of Glengarriff and Kealkil.

Lieutenants Donal McCarthy (Drinagh), Michael Crowley (Glandore), Captain Patrick Cooney (Skibbereen) and Bantry native brigadier commandant Gibbs Ross were all killed in the fighting in Bantry on August 30th 1922.

One of the final official casualties of the war in West Cork was Lt Denis Kelly, an anti-Treayite killed near Kealkil in April, shortly before the death of IRA chief of staff Liam Lynch in the Knockmealdown mountains. Kelly’s death was recorded by a contemporary National Army report, although as John Borgonovo, Andy Bielenberg and James S Donnelly Jr note, the republican monument in Castletownbere records Kelly’s death as taking place on September 17th 1923. In November 1922, National Army soldier William Cronin, originally from Skibbereen and later living in Bantry, was killed in an ambush on the Durrus Road outside his adopted hometown.

The same month saw a large and fatal engagement between the factions at Ballineen that lasted several hours.

Glaswegian William Williamson Jr was killed the same month fighting for the National Army. As in all wars, a number of innocent bystanders were caught in the crossfire during this time and paid the ultimate price.

One particularly poignant case is that of Patrick Murray of Kenneigh and Séamus O’Leary from Bandon district. Arrested as suspected members of the IRA, they and their fellow prisoners were ordered to remove a barricade by the National Army.

In doing so, they set-off a trigger mine left by the IRA and both Murray and O’Leary were killed. Another man, John Desmond, died of his wounds a couple of weeks later. We naturally associate the words Upton Ambush with the War of Independence period, but it was also the sight of a deadly episode during the Civil War that claimed multiple lives.

On October 4th 1922 three members of the IRA were killed there by National Army soldiers in contested circumstances with arguments that the three Volunteers killed were shot while in custody, an embitteringly common occurrence definitively proven in other cases during the war.

While the amphibious landings at Passage West and Union Hall were central to the capture of Cork City, naval tactics continued to play a part in the Irish Civil War. On December 7th 1922, a large number of troops sailed into Bantry Bay. In the ensuing round-ups in the region, Anti-Treaty soldiers George Dease of Castlehaven and Seán Dwyer from Castletownbere were killed the following day near Kealkil.

Their deaths were, however, overshadowed by the execution of another West Corkman in Dublin on the same day. Richard ‘Dick’ Barrett from Hollyhill, Ballineen, and formerly principal of Gurranes national school.

A veteran of the War of Independence, he later served as Assistant Divisional Quartermaster and assistant quartermaster general of the anti-Treaty IRA at the commencement of the Civil War.

He was part of the Four Courts Garrison and was captured after its surrender on June 30th 1922. On December 8th 1922, he was executed along with three other anti-Treaty leaders as a reprisal for the assassination of Seán Hales, in an incident that also wounded his fellow TD, Pádraig Ó Maille.

Perhaps one of the more surprising facts about the Civil War in West Cork is that despite the region’s high levels of violence during both the War of Independence and Civil War, no executions took place here while one solitary official execution was carried out in Co Cork as a whole.

In the new year, Capt Laurence Cunningham of the IRA died as a result of wounds he received following a raid on a pub in Lyre, outside of Clonakilty in February 1923.

The well-known guerrilla fighter James ‘Spud’ Murphy was wounded in the same incident. A day after Cunningham’s death, 21-year-old National Army soldier Michael Aherne/Ahern was shot in Skibbereen district, dying two days later.

Cunningham’s death mirrored that of Thomas Lane of Shannonvale. Lane was similarly shot at a public house outside Clonakilty (Ring) on St Stephen’s Day 1922 in which a well-known guerrilla fighter (John ‘Flyer’ Nyhan) was wounded but survived. National Army soldier Michael McDonald (22) was killed in the same incident.

Margaret ‘Maggie’ Dunne was one of the few women to be killed in the conflict.

Dunne was shot by National Army in her homeplace of Adrigole in alleged attempt to alert IRA men of the presence of Free State troops in the district. At her large funeral her coffin was covered in the tricolour and an IRA firing party stood over her grave. This kind of memorialisation and commemoration was to become a central part of remembering the vicious fight that tore families apart, while others sought alternative outlets to cope with their own personal traumas.

• Alan McCarthy is a historian of modern Ireland. He is the author of ‘Newspapers and Journalism in Cork’, 1910-23 (Four Courts Press) and the forthcoming history of adult education and lifelong learning at UCC, 1946-2021.