On a warm November evening in 1916 a Boston ‘streetcar’ plunged into the cold waters of Fort Point Channel, killing 46 passengers. The driver was Skibbereen man Gerald Walsh

By Eric Moskowitz

THE faint glow of dusk had given way to the deep black of night by the time the streetcar clattered up Summer Street in Boston at 5:25pm, its sole headlight and the scattered street lamps waging a losing battle against the darkness.

On an unusually warm fall evening — Tuesday, November 7th, 1916, election night — the rush-hour ride home was something to endure, stuffy and loud: nearly 70 commuters packed into a rumbling shoebox with seats for 34, the straphangers squeezed by knees and toes on all sides.

The crush of riders spilled out onto the closet-sized platforms on both ends, flanking the motorman in front and hanging off the back stairs, as the inbound car crested the hill approaching Fort Point Channel, in the industrial end of South Boston.

The race for the White House was on everyone’s mind, amid unrest on the Mexican border and a war raging in Europe.

Few inside the streetcar gave much thought to the final screech of the brakes or the thump that came with it. Trolleys were always whining, and sometimes they hit things — like a wayward wagon, or a tip-cart stuck in the tracks — and kept right on going.

Except suddenly there was commotion and muffled cries at both ends. The car had smashed through the warning gates of the open Summer Street drawbridge and was skidding toward the edge.

Screeching, sliding, it seemed to slow just in time, pausing at the brink, the front end dangling above the water, the rear wheels holding onto the tracks.

The car rocked; it teetered for a second, for two. The lights cut out — the trolley pole slipped off the overhead wire — but still it wasn’t clear to everyone inside what was happening.

Then wood splintered, metal popped. The trolley snapped free, plunging forward, abandoning the rear wheels on the tracks. Someone shrieked — “My God! We’re going over!” — and the passengers tumbled, screaming and reaching out for one another as the streetcar fell.

Dark green with white trim, Car 393 had pulled out of the P Street barn in South Boston 12 minutes earlier, an extra car added to the schedule so the Boston Elevated Railway Co could move more commuters at rush hour. Motorman Gerald Walsh and conductor George McKeon were on board, both “spare men”, assigned to plug gaps in the schedule.

They had not worked together, and neither had worked this specific route before among the 486 miles of trolley track operated by the private company known as the El. Still, both men — blue-eyed Irishmen in their 20s — lived in the neighborhood and knew the turf.

Walsh, one of 10 children, had grown up on a farm outside Skibbereen before setting sail the previous year on the SS St Louis, enduring nine days in steerage to join a handful of siblings already in Boston. Just five months earlier, he had been hired by the Elevated as a motorman, following the lead of his twin brother. After two early accidents, he was feeling steadier now at the controls.

McKeon had been born in Boston, his grandparents on both sides refugees from the Great Famine of the 1840s. He had worked at a dry goods store until getting hired by the Elevated the year before.

They were workaday men assigned a workaday car. Its narrow passenger compartment was 25ft long, not counting small platforms on either end. Inside, cushioned benches ran beneath the rows of windows and advertisements. The car was 16 years old, designed for electricity and not a retrofitted open-air horsecar from the 1870s, but it was showing its age just the same. To protect the motorman from weather and debris, the open platforms had been enclosed a decade earlier with windows and folding doors. But the car still had a gooseneck handbrake that had to be cranked, not the fast-acting air brakes of the newer trolleys in the fleet.

At 5:13pm, Walsh nosed it down P Street and along a few residential blocks, while McKeon braced for the East First Street factory crowds that would pile on faster than he could collect fares and pull the cord on the overhead register.

Small workshops and sprawling factories lined East First, backing out onto the wharves of the Reserved Channel. The biggest was Walworth Manufacturing, the firm that had put the first radiators in the White House and dominated the plumbing supply business.

Two dozen Walworth workers rushed on board, all of them men and nearly all immigrants banging out a living in Boston with their hands, drawn to an industrial city that had doubled in population over the last 30 years.

At the corner where L Street met Summer, the car collected workers from the smoke-belching power plants of the Elevated and the Edison Co, neighboring behemoths that generated electricity for streetcars and streetlights, and from smaller shops like Stetson Coal, Condit Electrical Manufacturing, and JW Moore Machine, makers of gauges, jigs, and fixtures.

They included Norris Curtis, a 30-year-old Moore machinist looking forward to his upcoming wedding to a Jamaica Plain typist, and Elsie Wood, a 19-year-old Condit stenographer who turned heads as the only woman on the car, with her blonde hair and gold bracelet.

By then the car was full, every seat, every strap. Walsh crossed the first drawbridge without incident, over the Reserved Channel, where the Army was building a supply base on the far side. There were still 1â€iles to go.

In the distance, a tugboat whistled.

That familiar sound — two long blasts, two short — stirred the men inside the drawtender’s house on the Summer Street Bridge, a Tudor cottage that belied the modern mechanisms of the drawbridge itself; instead of lifting up, motorized sections of the bridge retracted at angles to each side, clearing a passage. Down below, the tug William G Williams waited to tow a barge full of raw sugar up the channel to the big refinery beside South Bay, near the Gillette plant.

Drawtender Timothy Shea had been working the bridge almost since it was built in 1899, thousands of routine draw openings and checkers games punctuated by occasional excitement. He went to the control room and sent his assistants out to the deck, one to each end, to close the gates and hang red kerosene lanterns to warn oncoming traffic. A few hundred yards south, Shea could see the headlamp of a streetcar.

Sticking to his schedule, Gerald Walsh was motoring that car at a brisk 10-15mph, McKeon in back doing his best to change dimes and collect nickels, more than 40 people aboard now. They stopped at the C Street viaduct and 20 more pressed on, half from the Boston branch of telephone manufacturer Western Electric and half from the new Fish Pier nearby.

Amid the cutters and packers, the group included buttoned-up salesmen as well as 20-year-old bookkeeper Lillian Frank, whose struggling parents had given her up to relatives as a girl, and who was busy on weekends now competing in gymnastics and planning dances at the Hebrew Y. Also coming aboard was Thomas Price, a window-washer and handyman popular along the pier. The Kentuckian stood out less for his drawl than for being one of 15,000 black residents in a city of 750,000, part of a wave of migrants settling in the South End.

Up front, Walsh peered into the shadows beyond the modest beam of his headlight. Near the intersection with Melcher Street, right before the bridge, a rectangular sign hung on a wire over the road. STOP, it warned, 20ft in the air. Walsh didn’t seem to notice that, but he spotted a man waiting beside the road and slowed — without stopping — so the guy could jump on.

Walsh nudged the controller handle, and the car regained speed — 5, 10, 15 miles an hour, it was hard to say. Suddenly, Walsh spotted a set of metal gates blocking the road 30ft away. For an instant, he froze, then he grabbed the brake handle with his right hand, yanking so hard it bent. But the car was moving too fast; the wheels locked, skidding along the tracks, the metal white-hot.

Walsh was frantically trying to throw the controller into reverse with his left hand when the car crashed through the gates. Just 25 feet remained now before the edge of the draw. Walsh found his voice, crying out, “Jump!”

On the sidewalk, across the bridge, on the tugboat below, bystanders turned at the sound of the crash and saw people leaping from both ends of a streetcar as it skidded toward the edge of the draw and teetered over the channel.

On the front platform, where the handful of riders around Walsh could see what was coming, everyone leaped to safety, tumbling onto the roadway atop the bridge; Walsh followed, just in time. On the back platform, it was bedlam.

Lillian Frank, still standing near the door, felt a sudden shove from behind — where her co-worker Nelson McFarlane had been standing — and flew into the air. Instinctively, she reached out to grab for the car. Then she smacked the ground, rolling to a stop by the edge of the bridge, where a stranger’s hand reached out to hold her back.

Some heard shrieks, others chilling silence. A few car-lengths back, Christopher Thompson, a Western Union messenger boy who’d been stealing a ride on the rear fender, dusted himself off in the street. At the squeal of the brakes, he had hopped down — thinking the car was stopping and the conductor would catch him hooking a ride. He first looked back, wary of getting flattened by an oncoming horse team or automobile. Now he turned toward the trolley, just in time to watch it plunge.

Thompson ran to the edge. He thought he would see 30 people down below, splashing and calling for help. Instead, he saw just seven or eight, and no sign of the car.

With the rising tide halfway in, the drop to the oil-slicked surface was roughly 20ft, and the water itself 30ft deep and climbing. From the tugboat, Captain Harry Ross had watched the people writhing and grasping at the air as they fell alongside the car. The heavy trolley appeared to smack a wooden beam partway down and then plummet toward the water, throwing up a splash, sinking with a gurgle that could be heard outside South Station.

Ross sounded the bells and shot his tug toward the spot where the trolley went down, calling for his men to toss the rings and grab the lifeboats. They quickly hauled in three passengers, all of them floundering in the chilly water under heavy layers of clothing.

Atop the bridge, Shea shouted from the control house, and the two assistants who had closed the gates on each end sprinted down the bridge steps and dropped into a rowboat, helping to pull in three more. Down Summer Street, people who had been walking home in the warm weather ran to help, banging on the doors of the NECCO candy factory, calling for ropes.

In the water, Nelson McFarlane, who had pushed Lillian Frank before jumping as the car went over, popped back to the surface. He had just turned 17, an amateur boxer from Dorchester working by day at the Fish Pier. He was swimming toward the South Boston side of the channel when he noticed an older man thrashing, struggling to keep his head up. Grab my leg, McFarlane shouted, and he towed him to the edge. Rescuers hauled them both up, and then McFarlane, hatless and dripping, started to run across the bridge deck. Amid the alarm gongs now ringing in the night, hospital ambulances and fire engines charging to the scene, McFarlane shouted something no one could make out, and collapsed.

Inside the pitch-black car, the rush of cold water had shattered some windows and swept in through the doors, climbing quickly to the ceiling as the trolley sank to the muck. The panicked passengers, unable to see, unable to breathe, flailed and clawed; they tugged whatever they could touch, hoping desperately to untangle from the scrum and push or grope their way out.

Arthur Smith, 23, a Fish Pier salesman, felt a boot in the eye, then swift kicks to the ribs. Tall and strong, the former Arlington High football player worked his way backward and felt a window pane, then butted the back of his head against it, smashing the glass. He started to swim out — and got stuck, overcoat snagging.

Wriggling, trying not to panic, ears popping, lungs clenching, Smith felt one arm burst free of his coat, then another. He kicked to the surface, gasped, splashed, and smacked something with his hand, timbers at the base of the draw. Clinging with his fingertips, he cried out. A rope dropped from above. He gripped it with both hands and clamped down with his teeth, determined not to let go until he was firmly on land.

A patrolman directing rush-hour traffic at South Station heard the crash, saw what happened, and ran to an alarm box to flash word to the Lagrange Street district station. Soon, the news crackled across telegraph wires and telephone lines. From its berth near the mouth of the channel, Fireboat 44 steamed toward the Summer Street bridge, piercing the air with siren blasts.

Jumping in with his driver at fire headquarters, senior deputy chief John Taber roared to the accident site. A veteran ‘smoke eater’, he had responded to every major Boston disaster since 1888. But he had never seen anything like this.

At the fire box, he tapped an emergency call for more ambulances, more ladders, more ropes — and a second call seeking divers from the wrecking companies and contractors who worked the waterfront. Already the first ambulances were rushing survivors to City Hospital and the Relief Station at Haymarket Square, but what of the scores still trapped below?

Taber, who had seen gasoline-powered fire engines replace horses, prayed that the speed of the trucks and the marvel of the new Pulmotor, a device to pump oxygen into the lungs of the unconscious, could save their lives — if only they could be freed from the unseen car.

At City Hall, first-term Mayor James Michael Curley had just reached his office to review election returns, exhausted from weeks of Democratic stump speeches and two straight days of parades for troops returning from the Mexican border. He wanted to sink into bed in the manse he had just built opposite Jamaica Pond.

But that all evaporated now, and Curley charged to the scene in his limousine, parting a crowd that had formed rapidly on the Boston side. At 5:50pm, he stood on the deck of the drawbridge and surveyed the water, searchlights now illuminating the rowboats, Curley’s ruddy face a mask of concern and sorrow.

Hoping some of those trapped might retain a spark of life, the mayor telephoned the Navy Yard, flagging down Commandant William R Rush to send sailors and divers and a massive floating crane. He put the Fire Department in charge of the rescue, and called on the Police Department to manage the crowds, with thousands now packing in and straining for a view. Curley feared the edge of the channel or one of the bridges might give way, that hundreds more would drop into the frigid water.

Detectives and reporters waded through the throng, seeking survivors and witnesses. They found motorman Walsh, ashen, wide-eyed, talking too fast. He insisted it had been dark, that the street light now shining overhead had been out, that the warning lantern now hanging on the damaged gate was not there, either, that he had tried desperately to stop the car, but the brakes failed him.

No, insisted John Fitzgerald, the bridge assistant who had closed the gates on the South Boston side, swearing that he had hung the lantern right before the car came crashing through, and that the street light had been shining, too.

Walsh stammered, insisting otherwise. As reporters scribbled, an Elevated official shot Walsh a look. ‘Haven’t I told you not to talk? Now keep quiet.’

In the water, illuminated by spotlights, firefighters and Harbor Police combed the muck with grappling hooks, searching for bodies and the streetcar.

At 6:45pm, gasps spread through the crowd. Three harbour officers in a rowboat had dragged up a body, roughly 80ft upstream from the bridge. They rowed now to the side of the Guardian, the flagship of the police fleet, and passed the body tenderly over the gunwales. It was a laborer — 30ish, maybe, in a blue serge worksuit, black shirt, lace-up boots, and knit coat, his hands clenched.

A few minutes later, a second body surfaced, shorter, slimmer, even younger, in a gray sack suit and checked mackinaw, the short coat of the working class. The bodies were covered in tarpaulins and brought to the rear of the Guardian, sheltered from view, where medical examiner George Magrath leaned in close. There were no signs of life, no hope for the Pulmotors. Beside him, priests from St James Parish administered last rites.

Few men in Boston were better known than Magrath, darling of the papers, star of the courtroom, recognised nationally as a father of forensic medicine. With his pipe and ribbon glasses, he was a Sherlock Holmesian figure who solved murders from microscopic clues hidden to police. But there was little mystery to solve here besides identity.

In the first man’s pockets, Magrath found a watch — stopped at 5:26pm — and a bill for George Wencus of the West End. The second man carried a receipt suggesting his name was Antonio Della Pelle; the initials on his belt buckle seemed to confirm it.

At 7:15pm, a fire captain using a lead sounding line struck the submerged trolley at the bottom of the channel. Soon, the great whistle of the US Navy tug Iwana could be heard from the harbour, and a small flotilla came into view, a crane rising from the centre. Mayor Curley and a clutch of officials boarded the Navy craft, conferring with the chief machinist. The crane could lift 10 tons safely. The trolley weighed 20 tons at least, more if it was packed with bodies. The crane would be no use.

The wrecking lighter Admiral steamed into view at 9pm, a behemoth mounted with a crane rated for 75 tons. Amid the dozen divers suiting up, the oldest would go down first: Peter Foley, a veteran of the waterfront working now for Hugh Nawn Construction Co.

Foley was a wiry bantamweight, 54 years old and 5’4”, a man whose real first name was Florence, his wife named Florence, too. As he donned his watertight suit, leaden shoes, and heavy helmet, he tried not to think of what he would find on the bottom.

All around, the brilliant searchlights made the whites on the sailors’ bell-bottoms and the brass buttons on the police and fire coats seem to glow, but all eyes were on the water, tracking the trail of Foley’s bubbles. Fifteen minutes later, his handlers felt a jerk on his line. Pull him up!

Foley was still clutching the ladder, his handlers removing his helmet, when the mayor called to him. ‘How does the car lie?

‘Just as she would if she were still on the rails,’ Foley said. He looked ashen. The car had turned around somehow, facing back toward South Boston. One end was battered; most of its windows were smashed. As Foley had circled it on the bottom, the hands and arms of trapped bodies brushed him as he passed by.

The plan had been to send the divers down to fasten the crane’s chains and haul up the car immediately, but they worried the bodies would wash out the open windows. They chose instead to send the divers in teams to tie ropes around the bodies and haul them carefully to the surface, one by one.

The first bobbed up at 10, and the boom of a news photographer’s flashlight powder caused people to jump. A searchlight showed the victim to be another young working man, his open eyes staring up. Police Supt Michael Crowley, called out in the night: ‘By order of the medical examiner, allow no photographer to photograph the bodies,’ said Crowley. ‘All officers will enforce this order.’

And so it went, for three hours, the divers knotting ropes around the bodies and sending them up one by one, the searchlights being turned away each time a victim crested to the surface, the men all around removing their hats. As the divers worked, the street light closest to the gate flickered and went out for a few minutes, then came back on. Maybe Walsh had been right.

Still, at 12:40am, as the divers finished their work, Sergeant James Smith of District 6 arrested the Skibbereen motorman on manslaughter charges, taking him to the D Street station in a cab.

A half-hour later, with thousands still crowding the scene, Foley surfaced once more. The car was empty. Forty-four bodies had come up, all of them male; one more had been ruled dead hours earlier.

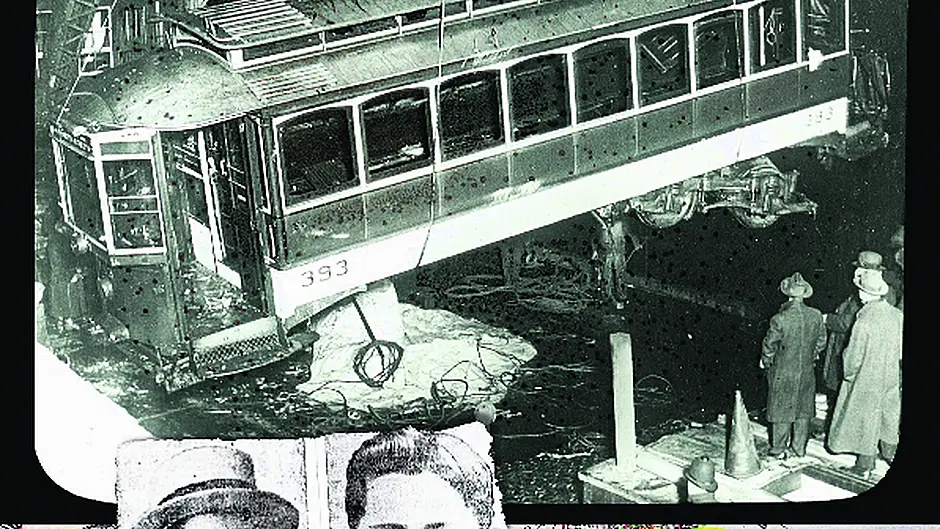

The great crane on the Admiral groaned, and the streetcar surged above the choppy waters at 3:30 am, 10 hours after the crash. Already the morning editions and the election extras cranked out by the evening papers were in the hands of the newsboys.

The stories did not mince words. ‘The worst tragedy in the history of the city,” the Journal wrote; the Globe concurred, dubbing it “the greatest catastrophe that has ever taken place” in Boston.

At noon, Magrath issued an updated list of victims, with 41 confirmed names. Investigators examining the trolley found no flaws besides the fresh accident damage, pointing only to poor visibility or human error. The twisted, battered brake handle showed how desperately Walsh had wrenched it.

On State Street, police arrested a hysterical bootblack, only to learn at the station that the man had lost two cousins in the accident, fellow Italian immigrants. In Revere and Roslindale, Chelsea and Cambridge, families made plans for funerals. The flag flew half-staff at the Fish Pier, which had lost 10 men; down the road, Walworth had lost 17, men who’d gone home as always one Tuesday evening, never to return.

On Thursday, one of the trolley’s signs washed up in East Boston and another in Winthrop, four miles across the harbour. On Friday, grapplers pulled long seat cushions from the bottom of the channel 50ft south of where the car went.

Readers sent money to newspaper offices, marked for the widows and orphans. Elevated officials promised to compensate any family that had lost a breadwinner.

The next week, the search for more bodies was called off. The investigation closed and the Summer Street bridge reopened.

The death toll remained at 45 until May, the worst streetcar accident in the nation’s history, when a body surfaced in the warming waters and someone spotted it bobbing beneath the Congress Street bridge. It was Elsie Wood, victim 46.

After a thorough investigation, the state Public Service Commission ruled that Walsh had been wrong to run the trolley right under a small, company-installed stop sign 200ft from the bridge, but that many bridges had no such stop signs and motormen often failed to heed them anyway. The commission called for widespread installation of larger, standardised stop signs, for mandatory stops by drivers, and for every city or town with streetcars running over drawbridges to set the warning gates at a ‘safe distance.’ They were to be painted with white and black stripes and hung with clearly visible red lights.

In October 1917, Walsh went to trial in Suffolk Superior Court. A total of 74 witnesses took the stand, including the conductor, George McKeon, who had been working his way toward the back door when the car went over. McKeon, who jumped, smacked his head, and blacked out before being rescued, was so shaken by the accident that he had still not returned to work. But he testified on Walsh’s behalf, saying that the car had been moving at a normal rate of speed, nothing strange about Walsh’s driving.

But others testified that the car had been going unusually fast, including Albert Case, a Western Electric credit manager who jumped from the front platform; he said Walsh hastily rolled through a series of stops from A Street until the crash.

The three bridge tenders swore that the street light was working and the red lantern had been in place. Several witnesses supported them; others did not. A police officer who walked the bridge on his beat said the street light had twice gone out earlier that week, relighting when he kicked it. And George Corning, the motorman on the last car to make it through before the accident, said the light was out when he crossed the bridge uneventfully at 5:18pm.

Defense attorney James Vahey, the carmen’s union counsel, said Walsh had done everything in his power to stop the car once he spotted the danger, and that the motorman would give anything to go back and live the day over.

The jury deliberated late into the night, and the next day returned a verdict: not guilty.

Gerald Walsh never again drove a streetcar. He worked at the A&P, served in WWI, visited his mother in Ireland, and returned to Boston. With his twin brother now high up in the union, Walsh got rehired by the Elevated, this time in the stockroom. Still haunted by the accident, he dropped dead from a blood clot at 41; for decades after, his family avoided speaking about the disaster.

McKeon, the conductor, went off to war, too, shipping off as a doughboy with the Army’s Yankee Division. On July 18th, 1918, his company was part of a counterattack against the Germans near the Marne River in the Champagne region of France. Private McKeon was killed, his death not reported in the Boston papers until October, a month before the war’s end. The City Council named a side street in his honour near the South Boston Marine Park, not far from the P Street car house where he briefly worked; today, the street and the carhouse are both gone.

For years, the disaster remained a grim measuring stick for Boston, mentioned immediately when a North End storage tank burst in 1919, killing 21 in a fast-moving wave of molasses; a Chinatown speakeasy collapsed in 1925, killing 43; or a streetcar jumped the tracks in Roxbury in 1939, killing six. Then an overcrowded nightclub called Cocoanut Grove ignited in 1942, trapping and killing a staggering 492, and the Summer Street Disaster receded into the mist.

Car 393 was repaired and returned to service, but few were willing to operate the ‘death car.’ So the car was turned into a wrecker, assisting with derailments, disabled cars, and track work.

Nearly all the streetcar tracks across the city were ripped out or paved over in the decade after WWII; this route, from City Point to downtown via Summer Street, stopped running on June 19, 1953. The next day a bus replaced it, and it still follows the same route. There is even a stop at Summer and Melcher street, where Gerald Walsh slowed without stopping, squeezing on one last passenger that fateful night.

Tugs no longer pull barges through the channel, and the drawbridge motors were removed in 1970. The bridge decks are now fixed in place. But the bridge from 1899 is still there, spanning Fort Point Channel right by South Station. In a city with historic markers and tablets every few blocks, there is not a word here about the 46 commuters who dropped to their death in 1916. But every few minutes at rush hour, another bus rumbles over the bridge, lights glistening in the water below.

Information about the accident and Boston in 1916 came from hundreds of contemporary articles in local and national newspapers; surviving public, legal, and genealogical records; multiple books; and interviews with descendants of victims and survivors.

This article was reprinted by kind permission of The Boston Globe