THE need for training in dealing with victims of sexual abuse and violence for gardaí, social workers, judges, teachers and other public sector employees was one of the findings of an extensive survey of victims and survivors of abuse in West Cork.

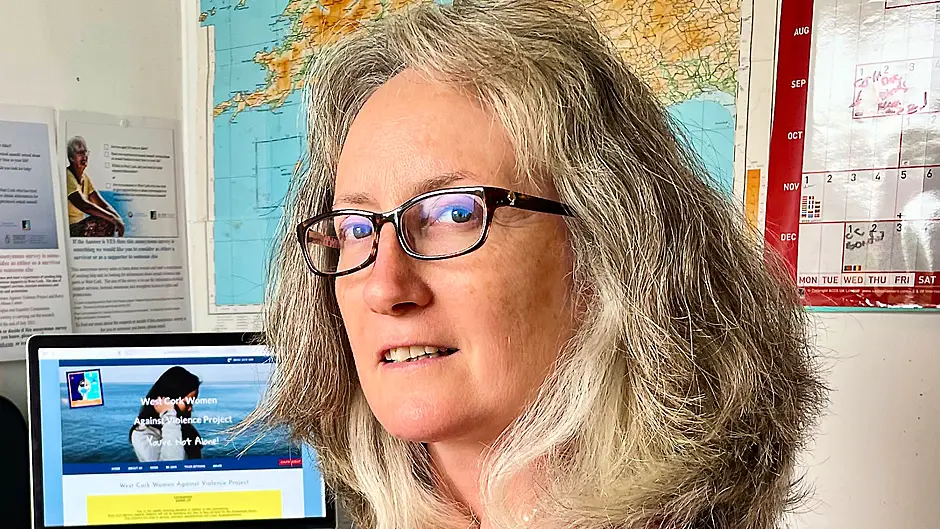

The survey, which was commissioned by the West Cork Women Against Violence (WCWAV) project in 2021, involved almost 30 survivors and their supporters, who anonymously shared their experiences of sexual abuse, assault and other types of sexual violence, and their experiences of seeking out supports and justice.

Conducted by Dr Caroline Crowley, the survey is about to be published as a report which WCWAV hopes will help design a better system for future victims in the West Cork area.

‘It is envisaged that the findings will be incorporated into ongoing work to develop capacity for a specialist sexual violence support service in West Cork,’ Dr Crowley says in the summary.

The survey revealed the need for four key changes in West Cork, namely: community-based prevention and early intervention services; a sex education and awareness programme that would include schools; a support service accessible throughout West Cork, and training for key professionals.

The project aims to share the findings widely, and has already taken steps to initiate training for employees of the various services that victims/survivors access in the course of reporting abuse.

The report points out that calculations based on the 2016 Census indicated that up to 12,000 people in the municipal district of West Cork alone, were directly impacted by sexual violence. However, only 30 people a year are reporting such crimes to the gardaí.

‘This points to the hidden nature of sexual violence in the region and suggests that barriers exist which made it hard to prevent people from getting the support and justice they deserve,’ it states.

The majority of respondents to last year’s survey were women, but two Irish men also participated. Over half of respondents identified as heterosexual and the remainder identified as either gay or bisexual.

One respondent said they felt ‘asexual’ because, following their experience, they have never been able to feel sexual attraction.

Half of the respondents had a third level degree, and over half were single (some in a relationship, a similar number not in a relationship), and the majority said their first experience of sexual violence was during childhood and almost all had experienced a sexual violence incident more than once. In all cases the perpetrator was known to the survivor and most likely to be a relative or partner, and most of the respondents had their experiences in West Cork.

They also noted the lack of timely access to supports, which caused them poor emotional health and sexual health problems, harmful coping strategies and a breakdown of trust in themselves, in others and in their safety.

The survey includes comments made by some respondents, including feelings of depression, avoidance, detachment and, in some cases, reliance on alcoholism. ‘I silently cried myself to sleep every night for years’, ‘The scar is always there’, and ‘You grow up fearful of everyone’ are just some of the many heartbreaking comments contained in the report.

One young respondent said: ‘I did not use the word rape because he hadn’t been violent (which I thought rape had to be).’ Some respondents said when they told a confidante, they didn’t believe them. Others got negative reactions from some gardaí, teachers, social workers, and even their own parents. Some felt their experiences were minimised, and another said: ‘I was told to stop making trouble.’

Some were so young, they didn’t know what was happening.Five survivors praised the gardaí for their ‘patient, understanding approach’ and a successful outcome.

The survey identified the need for a freephone service, advice on making a garda statement, specialised counselling and access to a dedicated refuge.