This week marks the 60th anniversary of the controversial closure of the West Cork Railway line. Niamh Hayes reports on a much-loved service that had a connection to every major town

ON March 31st, 1961, the last train left Clonakilty station bound for Cork city and with it, over 100 years of jobs, economic growth, trips and excursions vanished, leaving only memories for those who were lucky enough to use or work on the railway line.

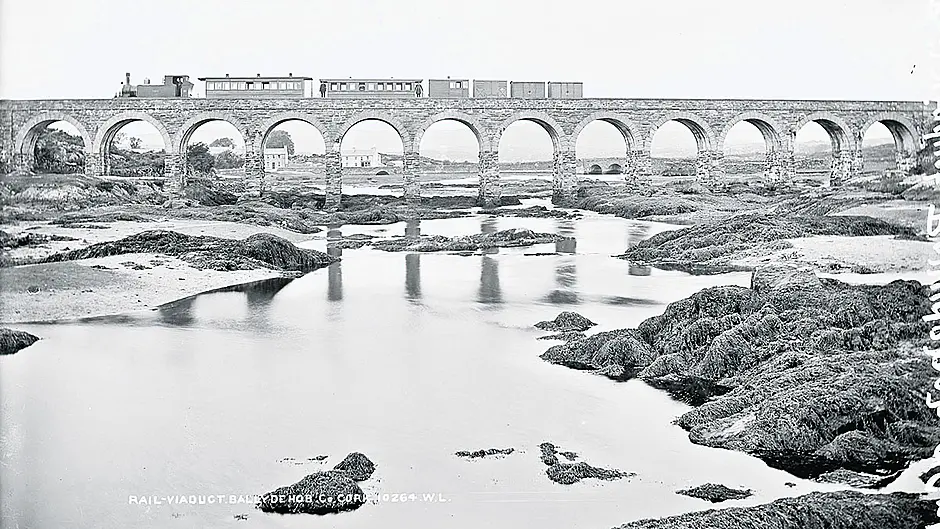

Construction on the ‘Cork and Bandon Railway’, as it was known at the time, began in 1844 and the first line, servicing Ballinhassig to Bandon, opened in 1848. This was only the beginning for the railway, which was to go on to service all the major towns in West Cork.

The initial line was extended to Cork city in 1851, and over the following 60 years, further extensions were made by different companies. The first came in the form of Kinsale Junction, with a new railway line opening in 1861 to service Crossbarry to Kinsale.

With the intention of extending the railway to Skibbereen, an initial line from Bandon to Dunmanway opened in 1866, followed by the Dunmanway to Skibbereen route in 1877. The Drimoleague to Bantry branch line followed in 1881.

Clonakilty, although a principal town in West Cork, still had no railway line by 1881. A campaign ensued and by 1884 work had begun on the line, which ran from Clonakilty Junction in Gaggin to Clonakilty town, eventually opening in 1886.

Joan Baker and her son Darryl at Timoleague station; a train at Clonakilty station and driver Paddy Twomey in Clonakilty.

Joan Baker and her son Darryl at Timoleague station; a train at Clonakilty station and driver Paddy Twomey in Clonakilty.

A year later, this branch line was further extended by a track which serviced Shannonvale Mills. No trains actually used this line, but instead horses pulled carriages along it to meet the train on the main track so that the produce from the mill could be transferred. An insidious task in today’s terms, it was a revelation in those days, making work much more efficient.

By this time, the Skibbereen to Schull narrow gauge had also opened and by 1888, the Cork and Bandon Railway had become the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway.

In 1890, an independent branch line opened from Ballinascarthy to Timoleague, followed by a further extension to Courtmacsherry the following year. This proved hugely successful with tourists. In just over two hours, passengers had left city life behind and were enjoying the beauty of the seaside villages.

The final pieces in the railway puzzle were the extension to Bantry in 1892, followed by an extension from Skibbereen to Baltimore in 1893, and a further extension of the Bantry line to service the pier in 1909.

Skibbereen station. Black and white photos: The Lawrence Collection: National Library of Ireland.

Skibbereen station. Black and white photos: The Lawrence Collection: National Library of Ireland.

West Cork to Cork city was now extremely accessible, albeit it did take well over two hours to get to some locations. However, undoubtedly, the sheer excitement of travelling on a train made the journey pass quickly, as well as the joyous anticipation of going to a GAA match at Páirc Uí Chaoimh, or a visit west to Baltimore Regatta, Clonakilty Show or Dunmanway Races.

The railway was incredibly important in terms of economic growth for West Cork. Not only did it bring tourists, but it was the only means of bringing goods into the area for a long time. It was also instrumental in transporting the beet which was grown around West Cork.

The line was taken over by Great Southern Railways in 1924 and by the Irish State in 1945, but by then, the closures had already begun.

The shutdown of the railway wasn’t sudden, rather it was a gradual winding down that occurred over 30 years. With less people travelling on the trains, there were more cars on the roads, and trucks provided a more efficient transport service for goods.

The Kinsale line was the first to go, with services finishing in 1931.

The Skibbereen to Schull route was next, closing in 1947, as well as the Courtmacsherry line in the same year. However, excursion trains did continue to go to Courtmacsherry during the 1950s, due to the seaside village’s popularity.

The closure didn’t happen without opposition. When news spread that the decision had been made to close the entire railway line, the West Cork Railways Association formed the Save Our Railways committee, which wasn’t going to let it happen without a fight.

It fought right until the end, but the last train left Clonakilty station at 4.45pm on Good Friday 1961.

Baltimore station.

Baltimore station.

In the space of a year, one would be forgiven for thinking there was never a railway in the area. The land was sold, as were the timber sleepers – with some sent to Nigeria which was constructing its own railway.

However, what did remain were some incredible engineering and construction feats, such as the Chetwynd and Half Way Viaducts, and Goggins Hill and Kilpatrick Tunnels.

As the years slip by, it would be a shame for the railway to be completely forgotten, but thanks to projects such as the Joe Walsh Walkway and the West Cork Model Railway Village in Clonakilty, it surely won’t.

There are also hopes for a greenway from Skibbereen to Baltimore.

There is surely an appetite now for similar projects to be developed to ensure the memories of the West Cork Railway are kept alive.