Today we shortlist four strong candidates in the Drystock category ranging from Ballinascarthy in the east all the way out west to Cape Clear. Tomorrow we’ll announce our ‘Hall of Fame’ winner, followed by the ‘Young Farmer of the Year’ finalists, then our new ‘Sustainability’ award winner and finally the winner of the ‘Outstanding Contribution to West Cork’ farming award.

Awards ceremony and guest speaker

The West Cork Farming Awards 2021 ceremony is scheduled for Friday, 19th November at the Celtic Ross Hotel, Rosscarbery with special guest speaker Maragaret Hoctor.

Margaret speaks, lectures and coaches on farm diversification and gives practical advice and tips around mindset, entrepreneurial thinking and vision for farmers. www.margarethoctor.com

DRYSTOCK FARMER OF THE YEAR FINALISTS | Sponsored by Bank of Ireland

Brennus Voarino | Cape Clear

A FRENCH geologist is farming a beef suckler herd of pedigree Scottish Belted Galloways on Cape Clear and he can hardly keep up with demand for his animals. Brennus Voarino moved to Ireland with his family from south-east France (near Nice) in 2007. His parents bought the farm in 2008 and Brennus fell in love with farming and island life.

He studied Geology in UCC and Volcanology in Bristol and took the reins of the 100-acre dry stock farm three years ago. Initially a mixed Angus and Hereford suckler farm he made the pretty radical decision to change to Belted Galloways and after visiting Scotland, he imported six heifers from two herds he had seen there. It was a 30-hour trip to their new home, but it didn’t phase the tough breed in the slightest.

‘As a newcomer to farming I wanted to make things easier for myself. It’s a breed that’s easy to care for, they don’t have horns and are easy to calf. They’re also very suited to being out-wintered and we don’t have sheds,’ he said.

The hardy herd (now comprising 30 head of cattle including bull, calves, heifers, and steers, all of whom are Belties except for one original Angus) have settled in very well to island life and ‘are doing a great job cleaning up overgrown, marginal hilly land.’

He sells his pedigree heifers to other farmers for breeding and says there’s big demand for his animals due to their strong genetics. ‘I finish the males and they’re 100% grass fed and are a high quality product. We sell these directly to local customers including chef Ahmet Dede at the Michelin starred Custom House in Baltimore,’ he said. Brennus also has 15 breeding Lleyn ewes and a ram.

This is also a low maintenance breed and he sells the lambs to local butchers and to other islanders, but doesn’t breed for replacements.

Last year he completed his green cert in Darrara and his philosophy on beef farming is to have minimal input in an extensive farm system. ‘I want everything to be as natural as possible, our cows only eat grass, we never need to worm them and they almost never need the vet.’

Brennus is improving the farmstead all the time, particularly the areas of fencing and reseeding. ‘We’ve done a lot of reseeding over the past few years in a bid to get rid of scrub and ferns. We’re not certified organic but we don’t use chemicals and only ever fertilise with lime.’

Farming on Cape Clear can bring some challenges but he says there’ s a great spirit of co-operation among the island’s 15 farmers. ‘I wouldn’t want to farm in any other place - island farming is not always easy but I like a challenge! You have to be a “Jack of all trades” for sure though and at different times be the vet or the mechanic. It takes a lot more planning too, you can’t just drive to the co-op and everything has to go on the ferry, including livestock.’

His fiancée Samantha (pictured with Brennus above) keeps bees – she has 14 hives – and honey is sold locally.

‘Going forward, as the land improves the plan would be to get more breeding Belties. I’d also be very interested in developing a meat box enterprise,’ he said.

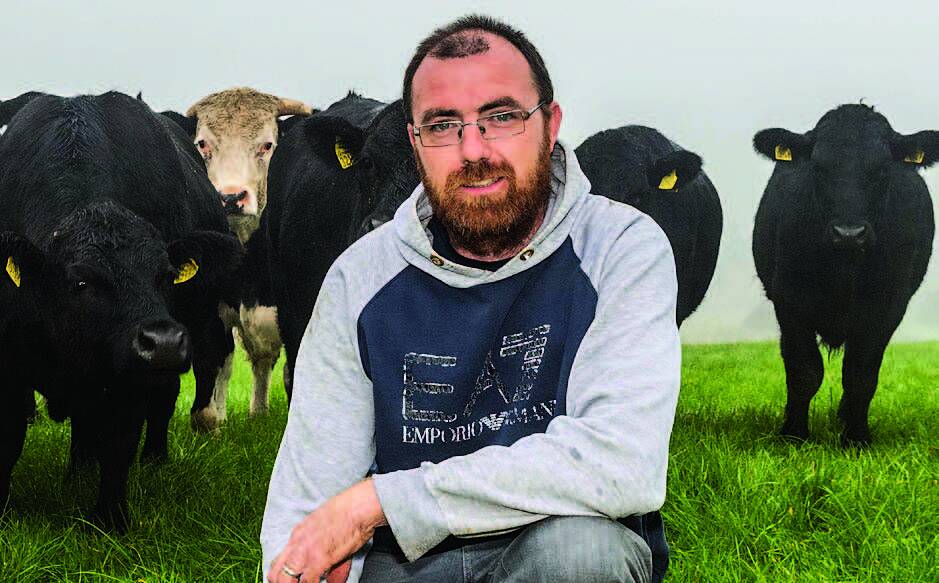

Aidan Coughlan | Skeaghanore

AIDAN Coughlan’s cattle possibly enjoy some of the best views of any in West Cork. Located almost on the beach, overlooking Roaringwater Bay, it’s a natural advantage that the young man doesn’t take for granted.

For starters it means happy cows! And animal welfare is something he places a lot of emphasis on. More practically, the temperate climate means a good supply of lush grass, which supports his efforts to farm non-intensively, and use as little fertiliser as possible. Farming with his father Michael (pictured above left) at Skeaghanore, the drystock farmers have 26 Charolais cows and calves; and another 15/20 drystock.

‘My father has been breeding Charolais for around 40 years and we use all top AI sires. We sell weanlings at between nine- 11 months at Skibbereen mart for beef, where they are in high demand due to their genetics. Our five-star bulls command top prices.

‘We breed our own replacements, aiming for top quality all the time. We have a split Autumn/Spring calving regime. Our weanlings have just been sold, and we’ve around nine cows after calving again,’ explained Aidan.

The father and son duo are very much motivated by the fact that they love what they do, and where they do it. ‘We like to do things right. We know we’re in a great location and we don’t want to do anything to jeopardise that. Our animals are very well treated, they’re well fed and strip-grazed twice a day. We don’t farm intensively, we’re not highly stocked, and we pay close attention to how much fertiliser we use,’ said Aidan.

That encapsulates my philosophy on beef farming: treat animals well, keep them on grass as long as possible, and respect the natural environment, while working to breed the best quality animal you can.’ Aidan also has a degree in horticulture and studied at Waterford Institute of Technology and Kildalton Ag College (the green cert was included in the course).

He has his own landscaping business AC Landscaping, employing one person full-time, and several others part-time. Customers are located throughout West Cork and he offers construction, design and maintenance services.

Aidan and Michael also have a potato business: ‘We started around seven years ago, and set three acres every year with early season mainly British Queens. We supply Fields’ Super-Valu and Drinagh in Skibbereen,’ said Aidan.

This enterprise compliments their farming operation and has resulted in nearly 80% of their land being reseeded, with clover in all mixes. They’ve also carried out extensive reclaiming and fencing work across their 70 acres (a mix of owned and rented, over several blocks).

Aidan says he’s learned everything he knows about farming from his father: ‘He built up the herd, and put solid infrastructure in place in terms of slatted sheds etc and I’m very grateful for that.’ His ambition is to finish their cattle off their own land and sell to factories: ‘I feel that as we’ve done all the hard work – dehorned them, tagged them, brought them so far – that I’d like to finish them myself.’

Clive Buttimer | Ballinascarthy

CLIVE Buttimer, Ballinascarthy runs a mixed tillage and dry stock enterprise on the farm he grew up on and is working hard to future proof it for the next generation.

A trained structural engineer, he made the career change in 2010 when he started farming with his dad Victor. ‘We finish around 600 animals a year, which we buy as stores. Some we keep for three months, others for six, more for the year. We run a trading system, and respond to the market,’ he explained.

The animals are grass fed for as much of t he year as possible, and during winter months are fed on their home grown, high quality cereals. Clive grows winter and spring barley, spring wheat and sugar-beet on their 185 acre farm.

'The idea is to be 100% self sufficient ourselves, and we also sell straw and beet to neighbours,’ he said.

The herd is predominantly Angus and Herefords: ‘We had been buying Charolais and other continental breeds but we moved away from that, responding to what is in demand,’ explained Clive.

Currently they sell to Dawn Meats in Charleville but in an exciting venture are looking at diversifying into direct selling in the near future, under the name ‘Clonakilty Beef.’ Clive puts a very strong emphasis on sustainability across every aspect of the farm, which made him one of the Origin Green finalists in 2018. One sixth of their grassland is planted in red clover silage swards and multispecies grazing mixes including grass plantain, chicory and clover which are more nutritious for cattle and better for the environment.

He also plants directly into the growing grass so no expensive cultivation is required.

Through GLAS and off their own initiative he has al so planted 600 native trees on the land.

‘A lot of what we are doing can maintain production, while cutting inputs. It’s a win-win from a business and environmental point of view. There may be in an increase in management but if these practices pay their way and are good for the environment it’s a no brainer. We’re trying a lot of different things at the moment some will work, some won’t, its about finding what works in your system.

‘My philosophy when it comes to farming is to produce a quality product in a sustainable way,’ he said. Some indicators he’s on the right track include the spreading this year of 127 units of nitrogen per acre which is very efficient. ‘We’re talking about 13 tonnes of dry matter per hectare across the farm which is what we need for the system to work,’ he said. ‘! ere is hopefully scope to cut fertiliser as the multispecies swards become more established.

‘We weigh cattle regularly and monitor weight gains achieving 0.95kg/day while grazing and 1.1kg/day when housed for finishing.’

A father of three boys, he said he feels there can be a ‘narrative out there that farmers are profiteers.’

‘But this is my home, and my kids’ home, and in no way would I want to degrade it. It’s about passing it on to the next generation in an even better state than I got it.’

James O'Sullivan | Leap

JAMES O’Sullivan runs a calf to beef system across two blocks of land, one in Leap and a second in nearby Myross.

His operation sees him buy 80 mainly Angus calves every Spring (typically in March), fi nishing them at between 18-24 months. James has been farming since 2004 and previously ran a suckler herd, comprising 15 animals on the 25 acres on Leap. When he invested in a second farm in Myross in 2013 (with his brother, who remains a silent partner) he had an additional 55 acres to play with.

‘That put me at a bit of a crossroads,’ he said. ‘I had to look at what I had and see what suited best.’ With the benefit of the additional land, he made the decision to switch to a calf to beef enterprise, and invested in a slatted shed, which is in keeping with his attitude of ‘if you’re going to do it, you have to do it right.’

His philosophy when it comes to farming is to run an efficient, profitable and sustainable operation.

‘For example, Myross is 95% an island, and if out-wintering animals there I’m very conscious that there aren’t any issues with run off . It’s important to me that things are done right.’

He strives to finish as many of his cattle on grass as possible and has worked hard to improve soil, and spread lime.

‘Figures last year showed our ps and ks coming in at optimum 3s and 4s. Our ph also came in at 6.5, again in the optimum range,’ he said. ‘I’m also reseeding all the time and aim for 10-15% every year. I include clover in reseeding but also oversow it in permanent pastures.’

James buys his calves mainly off other farmers, and like all businesses, the bottom line is important. He sells directly to ABP in Bandon and aims for a carcass weight of between 240-260 kilos, or heavier, with a good fat content.

Factory prices are increasing which is positive. On the other side of the equation though calf prices have gone up considerably, and so have inputs.

A hefty three-week-old calf cost him €125 last year, but €180 this year, which meant that his 80 calves cost him an additional €4,000 in 2021.

However, James remains philosophical and upbeat: ‘Prices are important but they’re not everything. It’s far more important to me to focus on being as efficient as possible in what I’m doing, working to improve genetics and have animals on grass as much as possible.’

Indicators he’s on the right path include his beef output per hectare last year coming in at 1,000 kilos (based on 31 ha). Th national average per hectare is 469 kilos.

As well as farming he works full time as an AI technician with Munster Bovine.

‘I’ve been doing the AI work since 2009. ! ey actually compliment each other in terms of schedule. My busy time of year with AI is March to July and it quietens down now. And through that line of work it means that I get to develop good relationships with other farmers when it comes to buying calves. I get to see good quality animals, hopefully at a good price.’

Married with four children he quipped: ‘I suppose the farming a bit of a hobby but it’s one that has to pay for itself!'

Click here to read about the DIVERSIFICATION award winner