Several items of huge significance, relating to famous botanist Ellen Hutchins, have recently come to light.

By Robert Hume

SEVERAL items of huge significance, relating to famous botanist Ellen Hutchins, have recently come to light.

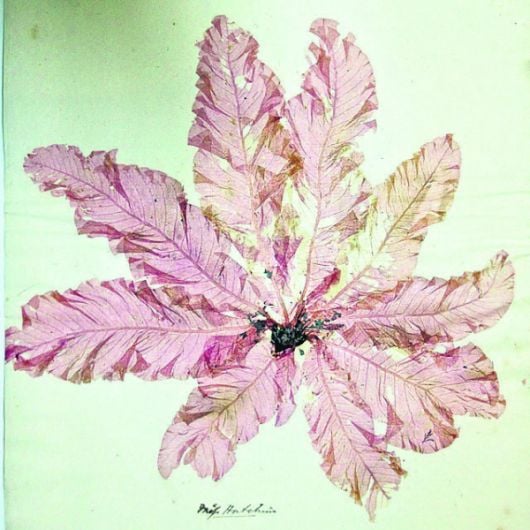

Though constantly dogged by illness, Ballylickey-born botanist Ellen Hutchins (1785-1815) succeeded in becoming an international authority on seaweeds, mosses and lichens.

History had largely forgotten her until last August when the Ellen Hutchins Festival commemorated the 200th anniversary of her death.

Miss Hutchins, who is now widely regarded as one of botany’s most distinguished scientists, died from TB, aged 29.

Her hitherto unmarked grave in Garryvurcha churchyard, Bantry, at last contains a plaque in recognition of her significant contribution to scientific knowledge. It was unveiled last year when admirers and relations in West Cork hosted the festival in her name.

Now, her great great grandniece, Madeline Hutchins, reveals new sources about Ellen’s life. These include a memoir by Ellen’s niece, Alicia, to be published online in February.

Searching in Trinity College’s herbarium recently for specimens collected by Ellen – ‘more in hope than expectation’ – a research team, led by Professor John Parnell, was stunned as more and more of her wonderfully preserved seaweeds came to light, all with ‘Miss Hutchins’ noted on them. In other correspondence files, the team discovered her letters to the botanist James Townsend Mackay, curator of the National Botanic Gardens at Glasnevin.

After she had sent Mackay a box of plant specimens, he returned her box full of plants for her garden at Ballylickey.

In September 1807, Ellen wrote to Mackay in delight:

‘All the plants you sent me are growing finely ... since you last heard from me I have been longing to tell you of all the sea plants I have got, of beauty and rarity.’

From another letter, one can sense her excitement:

‘I am to have the [family] boat and crew all the next summer to go where I please so that you may expect a good parcel at the end of it …’

Ellen also corresponded with two of her brothers. In a letter of April 3rd 1807 to her younger brother Sam, who was studying in London, she wrote: ‘I wish that you may be as successful in law as I have been in botany. I have made some discoveries in sea plants of some kinds entirely new.

Sam had already bought artist materials for her in London. Now she would ask him another favour:

‘Will you call on Mr Sowerby, No 2 Mead Place, Lambeth and enquire whether Dillwyn’s British Conferva is to be had. His work will contain some of the plants I have found here … [but] my name will not be mentioned as the finder. I have desired that it should not.’

As publication of her memoir and letters are eagerly awaited by plant enthusiasts, her exquisitely detailed watercolour drawings of plants can now be found at www.ellenhutchins.com, a new website set up by the festival committee.

The drawings are so lifelike that in a letter to her great friend, British botanist Dawson Turner, Ellen tells how a young girl who helped her collect and preserve specimens tried to pick one up, thinking it was the real plant.

And more finds may be in the offing for Ellen fans. After her death, a lock of Ellen’s hair was sent to Dawson Turner, whose letters have recently been bequeathed to the Norfolk Museums: ‘It is just possible,’ says Madeline, ‘that her lock will turn up.’

The Ellen Hutchins festival was awarded a prestigious National Heritage Week award recently.