Some names stand out when it comes to computers, like Charles Babbage, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, not forgetting Percy Ludgate who died 100 years ago next month

PERCY Edwin Ludgate was born on August 2nd 1883, in Townshend Street, Skibbereen — the youngest of seven boys and one girl — to Mary McMahon and Michael Ludgate from Mallow.

When he was young, the Ludgates moved to Dublin, but by the 1901 Census, the family had split. His father lived in Balbriggan, while Percy and his brother Alfred resided in Drumcondra with their mother.

Percy worked in the Civil Service, where he failed a medical in 1903 which prevented his promotion from ‘boy copyist’ to clerk. Instead, he applied to study accountancy at Rathmines College of Commerce. He went on to achieve a distinction in his final exam alongside a gold medal from the Corporation of Accountants.

The 1911 Census shows that Percy was a ‘commercial clerk (corn merchant)’ at Kevans and Sons Accountants on Dame Street in Dublin. A colleague there vouched that ‘he possessed characteristics one usually associates with genius’.

Percy never married, and appears to have spent his spare time taking ‘long solitary walks’. His niece, Violet Ludgate, says he was a regular churchgoer, and ‘a gentle, modest, simple man’, who never had a bad word to say about anyone. Every night, he would spend his time developing a machine capable of performing calculations ‘without the immediate guidance of the human intellect’ – a programmable computer.

The word ‘computer’ originally referred to a person who added up strings of figures – slowly, and with frequent mistakes. For hundreds of years, people had been searching for devices to do the work more efficiently. The abacus and slide rule provided some improvement.

In 1909 Ludgate presented the details of his contraption to the Royal Dublin Society in a paper entitled: ‘On A Proposed Analytical Machine’. Interest grew, and five years later he was allocated a chapter (‘Automatic Calculating Machines’) in the Edinburgh Exhibition Handbook. Ludgate ended his contribution with an astonishing claim: ‘I have myself designed an analytical machine’, capable of multiplying two, 28 numbers in less than 10 seconds.

Although aware of the name Charles Babbage – the ‘father of the computer’ – Ludgate claimed that his designs were original, his knowledge of Babbage’s work was ‘slight’, and he only became aware of it very late on. ‘It’s probably a fair assumption,’ according to Professor Brian Randell, a computer scientist at Newcastle upon Tyne University, as Babbage and Ludgate’s plans were so different.

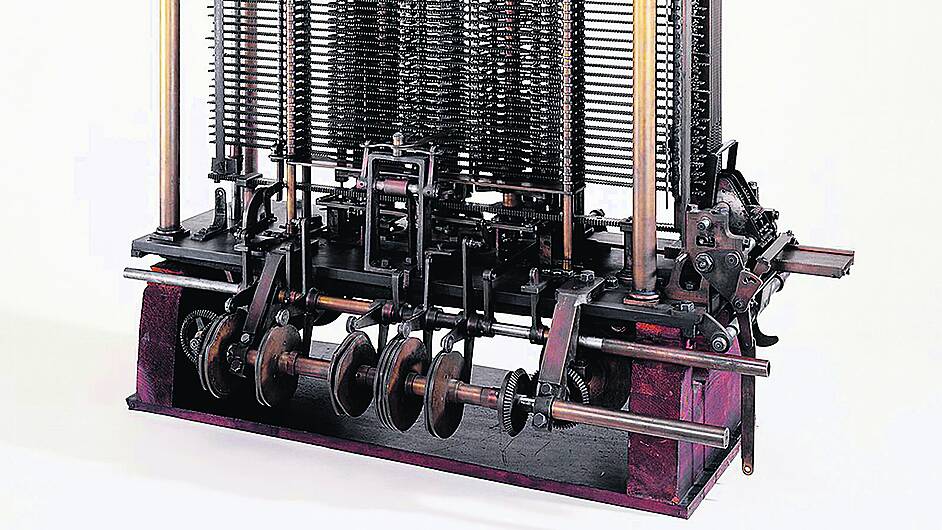

There were some similarities. Like Babbage’s apparatus, Ludgate’s was based on the principles of a loom, where punched cards direct the movements of different threads to produce a pattern. ‘It is not difficult to imagine that a similar arrangement of cards could be used in a mathematical machine to direct the weaving of numbers into algebraic patterns,’ wrote Ludgate.

Percy Ludgate.

Percy Ludgate.

But in other respects Percy’s plans were very different. Babbage’s ‘analytical engine’ would be powered by six steam engines, and reach the size of a house! Ludgate’s would be much smaller —a portable cube measuring 60cm per side — employing a single electric motor.

Babbage proposed two sets of cards for his calculator. One set would control the operations, and the other would select the numbers to be operated on. Ludgate, by contrast, intended using ‘one roll of perforated paper to perform both these functions’.

While Babbage proposed gear wheels and toothed sticks to store numbers, Ludgate preferred sliding rods and shuttles. New shuttles could be added at any time, ‘rather like a disk can be added today’, according to Randell.

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that Ludgate ever constructed his machine. No patent was taken out, and none of his drawings have survived.

During the First World War, his attention was diverted when Kevans & Sons appointed him to a committee organising the British cavalry’s oat supply. Sadly, he appears to have never returned to his computer.

In Autumn 1922, Ludgate returned from a holiday in Lucerne, Switzerland with pneumonia. On October 16th, he died, aged only 39, and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery. Professor Randell and others have been left to wonder what Ludgate might have achieved had he lived longer.

Today, Percy’s name lives on.

Since 1991, the Ludgate Prize – a €127 cash payment – has been awarded by Trinity College Dublin every July to the student completing the best Final Year project in Computer Science.

A century after his death, Percy Ludgate would gasp to see how advanced computers have become. Not a single ‘loom’ in sight, and engines that can even talk to one another! But would he be any less baffled than us reading the title of a recent Ludgate Prizewinner’s project: Ontology Free Domain Specific Summarisation?

The Ludgate Hub – template for rural development

A FEW doors from where Percy was born in Townshend Street, Skibbereen, lies the Ludgate Hub, the first digital start-up in rural Ireland.

Established in 2016 in Field’s Bakery, once a 450-seat cinema, the centre provides spacious workstations and state-of-the-art meeting rooms for local businesses to hotdesk.

The Hub’s digital education initiatives and its 1GB connectivity have helped transform the local West Cork community. Through its ‘propeller series’, the Ludgate initiative aims to aid ‘like-minded entrepreneurs’ in a creative collaborative environment, offering solutions for funding and investing, digitising, communicating and marketing.

The long-term objective is to facilitate 500 direct jobs and 1,000 indirect jobs for Skibbereen and West Cork, and help those people returning to the area.

Ludgate board chairman John Field described the Hub in 2018 as ‘a template for rural development, which has the potential to be replicated across Ireland.’

A second building, Ludgate At Fields (which opened in 2020), accommodates eight private offices in the former Roycroft Cycles building near SuperValu in Skibbereen town centre.

A third Ludgate building at the town’s former Mercy Heights Secondary School is still awaiting planning permission from An Bord Pleanála.