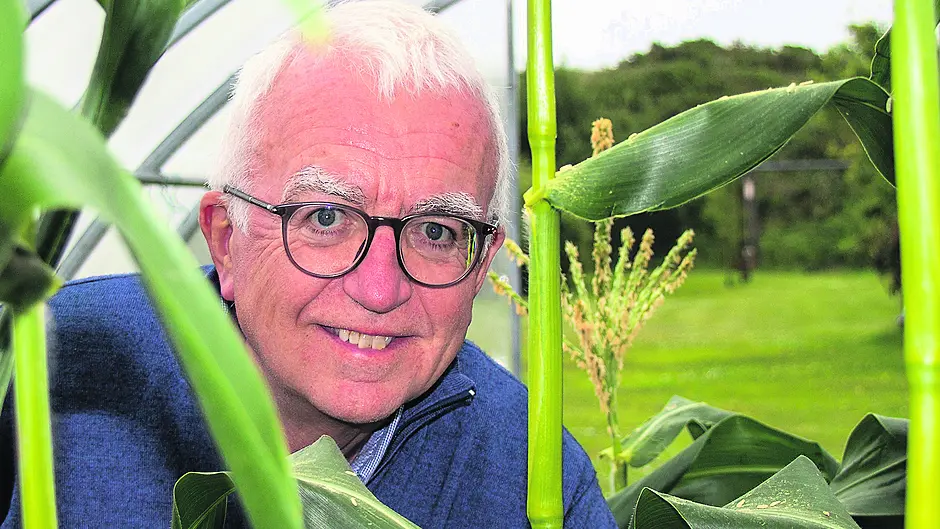

Newly arrived in West Cork, Peadar King has discovered the great joy in reaping what you sow. And if more of us embraced the practice, he says, the world would be a much better place

I HAVE taken to gardening since I arrived in West Cork. On Monday mornings, along with a number of others, we gather at 10 o’clock for a two-hour horticulture class at the back of what I am told is the old vocational school, Rossa College in Skibbereen.

This is how I start my week.

We are our own microcosm of West Cork, some who hail from Australia, South Africa and England, some of us who have come from other parts of Ireland, some who have lived here all their lives – all of whom call West Cork home, myself included.

There is something completely immersive in the act of gardening. It’s like breadmaking, but out of doors. Reaching deep down into the soil.

‘In the spring, at the end of the day, you should smell like dirt’, the Canadian writer Margaret Atwood tells us in her 1983 collection of short stories Bluebeard’s Egg. Earth on skin. Skin on earth. Feeling. Feeling its warmth, its coldness too. Feeling its possibility. This is tactile.

Nowadays, the practice is to wear gloves. I don’t.

A practice that comes with risks, I am told, but then again there is always soap and water. And risk? In this life, from risk there is no escape.

There is also something primeval about gardening, reaching back 14,000 years, some archaeologists tell us, connecting us back to generations and generations of people who have gone before us.

People who worked the soil. Harvested its richness. Sated their hunger. Then as now.

Then, but not quite as now. Farming has become industrialised, mass-produced. Standardised. Sanitised. Homogenised. Individualised. Colonised.

An extractive industry that tramples on and over our fragile ecology. All take and no give. You see it all over the western world.

Farming, the greatest cause of habitat destruction, the greatest cause of the global loss of wildlife, the greatest cause of the global extinction crisis. Ireland included. And in that respect West Cork is not a place of exception.

Nature on the retreat. Biodiversity in decline. Unsustainable practices leading to ecological degradation.

Such is the level of threat that a special sitting of the Citizens Assembly has been convened to address the biodiversity emergency. And yet more than ever the world needs food. It is now the ultimate human predicament: how to feed the world without devouring the planet.

As you read this, 690 million people around the world will go to bed on an empty stomach. More than 10% of the world’s population. That is according to the World Food Programme. To witness this is to remember it.

The yellowing hair of children. Their distended stomachs. The silent defeat etched on their parents’ faces. All of that I have witnessed.

The way we collectively produce our food is as skewed an industry as one can find, although there is fair competition when it comes to skewed industries. Producing food that cannot nourish the world.

Producing food for animals that are then fed to humans. Flying food half way around the world. Producing food only to discard it.

Producing food that makes us ill. Stuffed. Bloated. Obese.

According to the latest World Health Organisation (WHO) report, obesity has reached pandemic proportions in this country.

Punishing the earth for food that is punishing our bodies.

Punishing the earth for a food that is way beyond what those in dire need of food need or can ever afford.

Agricultural expansion is responsible for almost 90% of the deforestation that has happened this century, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). No wonder the earth is traumatised. No wonder the plants are traumatised. No wonder very many of the animals, birds and insects living off the land are traumatised.

And no wonder many of us humans are traumatised, food producers included. This is the stark legacy of the way in which we have violated the earth, mis-managed the land.

There is no individual blame in this. We have all lost our way. And we need to find a way back for our health, for our sanity, for our very well-being. And not just for human well-being. For the well-being of everything that walks, swims, crawls and flies.

For the well-being of everything that comes from the earth. For the trees, the briars, the flowers, even the weeds that are just plants out of place.

I am not naive enough to suggest that a group of people coming together on a Monday morning in West Cork can dent the global food crisis. For all of that, there is something important in that coming together.

About the collective effort of digging and planting, of nourishing the soil before extracting its harvest.

I am amazed at how quickly our disparate group has found a rhythm. How liberating and transformative the simple act of collective food production is. How the earth has nourished us. Lifted our spirits. Brought joy to our lives.

How immersing ourselves in the earth of where we now call home has helped us to find new roots, new connections, to ourselves, to each other and to this beautiful place.

On one particular Saturday morning, we will stand at Skibbereen market with our produce, along with all those farmers who bring us fresh produce Saturday after Saturday.

We cannot promise uniformity of produce or standardised goods. What we will have will come from the work of our hands. And that feels pretty good.