A sometimes Bantry resident, the mother of supermodel Emily Ratajkowski, has followed in

her daughter’s footsteps this year – by publishing her own very important and personal book

THE three members of the talented Ratajkowski family have achieved a publishing hat-trick.

My Body, the book written by the model, actress and author Emily Ratajkowski was a New York Times bestseller, whilst her dad, John Ratajkowski, an artist and teacher at the San Dieguito Academy, gave the world something that it didn’t know it needed – a fabulous book of bovine illustrations called Cow Tuesday.

Now, it is the turn of Emily’s mother Kathleen Balgley, a retired professor of literature, who has written a memoir entitled Letters to My Father – Excavating a Jewish Identity in Poland and Belarus.

It begins with Kathleen’s childhood discovery of her father’s hidden Jewish identity and goes on to explain how she unearthed more of her own suppressed Jewishness when she accepted a Fulbright to teach in communist Poland, just before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

With three million Jewish people living in Poland at the start of the war – the largest concentration of Jewish people throughout Europe – it became an epicentre of suffering.

Kathleen’s journey there was not a mere visit all those years later but a full immersion that led her away from her Catholic upbringing towards the Jewish faith.

The journey also forever changed the relationship she had with her father, Ely.

Kathleen, as her name might suggest, has Irish roots. Her mother – Margaret O’Hara – loved all things Irish and that played a strong role in her formative years.

But in the shadow of that light, this knowing child questioned the accented English and the samovars in the apartment of her grandparents in Brooklyn.

Later in life, Kathleen’s career took her to different places, including teaching dramatic literature in London, where she says Emily fell in love with theatre. But it was in 1987 – after teaching writing and literature at UCLA – that she accepted a Fulbright to Poland to explore the place where her father was born in 1912.

She was there for two years to teach but in 2012, with the help of a guide, Kathleen made it her mission to find her family’s records in what is now Belarus.

What she found was documentation containing the names of hundreds of people who shared her surname. The name was there on ‘page after page after page’ and they all had a ‘ghetto passport’, which Kathleen described as ‘a ticket to hell’.

‘It was shocking,’ she said, ‘to see everything written down.’ To someone else the documents might read like an historical account, but she found herself metaphorically ‘burying the dead’.

‘It was very emotional for me,’ said the author, who found herself in ‘the killing fields’ of her own family. There was just one reprieve in the emotional onslaught and that was when she found her father’s birth certificate.

Kathleen described her experience of teaching in Poland up to the time of their first free elections, and researching in Belarus, to be ‘bashert.’

It is a Yiddish term for soul mate or destiny, but Kathleen evokes it as ‘uncanny coincidence or serendipity.’ The word has since become part of her, burnished into her being. She even chose the name Bashert Press as the name for her publishing company.

After almost a lifetime of hiding his identity, Kathleen’s journey, and her letters home over a two-year period, roused in her father a desire to set foot on the soil he had previously forsaken – it having forsaken him first.

Together, Ely, a noted pianist, and her mother Margaret, toured the country and Kathleen recalls seeing an awakening in him as places – real from memory – brought him back to consciousness.

Reviews of the book speak of it as being ‘an epic of soul revival.’ It does, after all, deal with some of the most compelling issues of our time – identity, the need for belonging, war and the persecution of an entire people. But it does something else, too. It offers a lie to the truism, ‘You can never go home again.’

‘He saw my investment, my emotional connection to Jewish history in Poland, and that opened the door to us to talk about this unspoken family secret, and I finally understood why he did what he did, and I came to respect it,’ said Kathleen.

Ely had identified as ‘a city boy from Brooklyn.’ He was a virtuoso pianist who graduated early – at the age of 15 – from the Juilliard School of Music in New York City.

It was while working a summer job at a resort – the Eddy Farm – that he met his beautiful cailín. She was 16 and he was 21 but they were a love match and together they raised Michael, Jane, Kathleen and Elise as Catholics.

Kathleen met John Ratajkowski when she was teaching at San Dieguito Academy as a graduate student working on her doctorate.

‘I had always been interested in art and had written about it too,’ she said. But there were other pairings like the fact that John’s father was Polish, a gentile, and his mother had a Celtic background, Scotch-Irish. It didn’t hurt that he was handsome, and had a sense of humour, too.

As a couple, they first visited Poland in 1984, three years after John was invited to exhibit his art in Warsaw.

Kathleen’s recent return to their home in Bantry proved auspicious.

Just 24 hours after touching down on Irish soil, she learned that her book had been published. And 24 hours after that, she learned she had been given the ‘all clear’ for cancer.

Four years ago, she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and was told there is no cure for the blood cancer that affects white blood cells made in bone marrow. But Kathleen is now in remission.

Kathleen first came to West Cork with John 40 years ago, but it was the natural beauty of the area – and the friendships she was able to establish – that ensured her return.

‘I fell in love with Ireland before I came to Ireland – that came from my mother who had a reverence for Ireland,’ she said.

Kathleen was ‘stoked’, too, by her love of Irish literature and it was her paper on James Joyce that got her into her PhD programme.

‘I have returned enough to have established a community here,’ she said, although strict US travel restrictions during the Covid pandemic meant they couldn’t visit during the last two years.

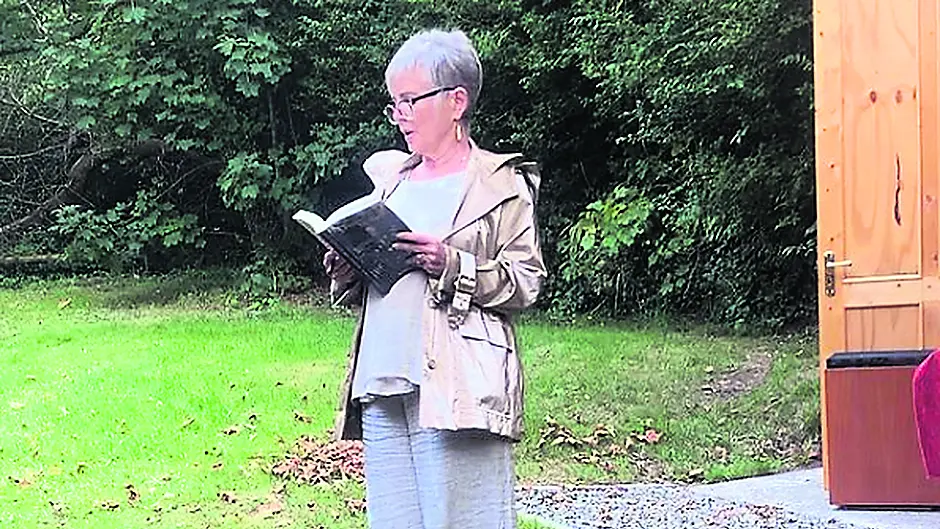

Hosted by Inanna Rare Books, the reading, and subsequent book signing, proved to be the perfect platform for Kathleen to tell her story.

The subject is complex and the book is weighty. So, too, is Kathleen’s almost forensic research and attention to detail. The subject demands it and anything less would not satisfy the reader.

At the end of a long conversation about religion, war, communism, literature and cancer, at her home in Bantry, there appears to be a mis-step.

It occurs when Kathleen is asked about beauty – hers in particular – because at 70 she still has the fresh, angular beauty of a young Liz Taylor.

There is an almost imperceptible bristle, but it disappears as quickly as it appears, and is followed by a small, genuine smile, and the opening gambit of an entirely new topic.

‘I am a feminist,’ she said. ‘I never wanted my goals and work to be usurped by physical appearance.’

A subject for another day perhaps ….