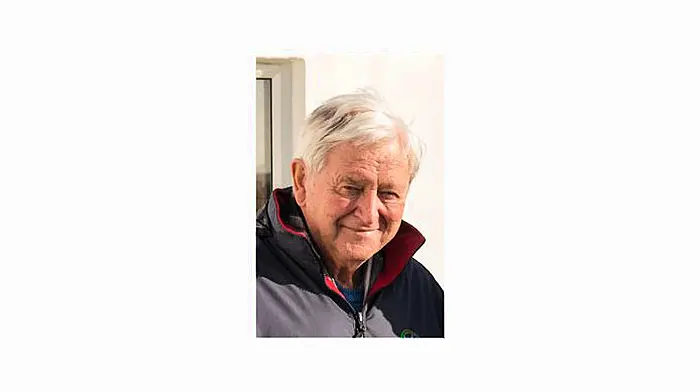

Locals recall for Brian Moore the bizarre week in 1986 when an unmanned giant of the seas struck terror just off the Cork coast as it drifted solo for days

Locals recall for Brian Moore the bizarre week in 1986 when an unmanned giant of the seas struck terror just off the Cork coast as it drifted solo for days

AS the huge bulk carrying cargo ship, the Kowloon Bridge, made its way across the stormy Atlantic that November thirty years ago, few people could have imagined that this ship was heading for a watery grave, just off the West Cork coastline.

The 965ft (twice the length of Croke Park) ship was sheltering from a bad storm in Bantry Bay when its anchor snapped.

Having already sustained damage while crossing the Atlantic, the captain of the Kowloon Bridge, with its cargo of 160,000 tonnes of iron ore, had just two choices.

He could stay in Bantry Bay and risk his ship being dashed against the shoreline or he could head back out into the raging storm.

The captain started up the engines and headed out into the Atlantic once more. The fierce storm was still raging, and the 50ft swells took another toll on the ship.

With the Kowloon Bridge taking on water, the captain issued a Mayday call, and the Baltimore lifeboat was launched.

‘When we launched, we knew that we could get to the Kowloon Bridge no problem,’ said Kieran Cotter, then the second coxswain on the lifeboat.

‘The conditions were terrible with huge swells and gale force winds, but getting there was one thing, whether we could get anybody off the vessel was another question altogether. As we approached the Kowloon Bridge, we could see that getting anyone off the ship was going to be near impossible, given the height of the vessel and the massive swells. If the RAF helicopters hadn’t arrived, I don’t know what we could have done.’

The helicopters removed all 26 members of the crew after the captain had set the vessel on what he hoped was a course out into deeper water, where it was assumed the ship, and its cargo, would sink.However, the weather and the seas once again had other plans for the massive ship. It headed back to shore and, as a large group of local people watched in horror from the shoreline, it started to make its way slowly towards Baltimore harbour.

‘I was 19 at the time, and I suppose looking back now, thirty years later, I didn’t understand the implications of such a massive ship sinking or breaking apart off the coast of West Cork,’ recalled Des Quinn, current station officer at Skibbereen Fire Station. ‘I remember watching the ship, all the lights burning, moving slowly past the beacon and I was amazed at the size of the vessel and the idea that there was no-one on board, at that point we all thought that the ship would just head off out into the Atlantic’.

A young photographer, 20-year-old Anne Minihane, accompanied her brother Denis on his assignment for the then Cork Examiner. ‘We watched it from the Beacon, and it was like watching a ghost ship drifting past,’ she remembered.

As the bystanders looked on, the Kowloon Bridge suddenly turned full circle and headed back out, drifting now as the engines had failed, towards Toe Head and the Stags rocks. At 11.30am, the Kowloon Bridge crashed against the rocks and finally came to rest, impaled on their jagged edges.

And there she stayed, nobody in control and all the ship’s lights burning brightly.

Fisherman Colin Barnes and his crew were the first to approach the massive wreck as it sat, immovable, on the rocks. ‘We were the first vessel to arrive at the Stags on the morning after. I remember how strange it was when we climbed aboard and found all the lights on and no-one about. It was very eerie,’ Colin said. ‘We went down into the massive engine room, and I will always remember the sound of the water gushing in and the terrible sounds of the steel hull bending and tearing.

‘But even at that point the vessel could have been removed and salvaged, and I will never understand why, when everybody knew about the oil and diesel that was on board and could have been easily removed, nobody attempted to do it.’

Anne and her brother joined Pat Deasy’s boat from Union Hall to get a closer look. ‘The weather was dreadful and it was a case of ‘take a photo, get sick, take a photo …’ I don’t know how I did it, but I guess we were all a lot younger then. I remember that I was given a brandy to steady my nerves when I got home,’ she said.

While the environmental damage afterwards was bad, Colin said, the Kowloon Bridge could have been carrying a full cargo of crude oil, as it had done on previous voyages. ‘If this had been the case, then this would have been a massive disaster, the effects of which we would still be living with today.’

And there on the Stags the Kowloon Bridge stayed as the government, the ship’s owner, the insurance company and the salvage teams all argued over the future of the ship.

Meanwhile, the turbulent seas and worsening weather took a terrible toll on it until finally, nine days after she hit the Stags, the ship snapped in two and sank.

As the vessel vanished beneath the waves, the oil and diesel tanks ruptured, spreading over 2,000 tonnes of fuel oil and diesel into the sea within sight of the shore.