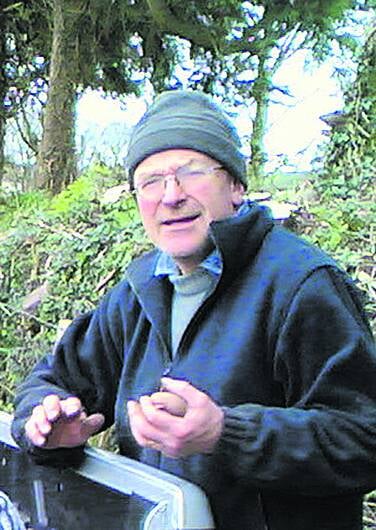

Stuart Kingston tells Emma Connolly that there are great opportunities in organic farming as the industry ‘needs new blood' in the right markets

Stuart Kingston tells Emma Connolly that there are great opportunities in organic farming as the industry ‘needs new blood’ in the right markets

THE market for organic produce is growing at a huge rate as consumers become increasingly frustrated with the amount of imports from Europe.

That’s according to beef and tillage farmer Stuart Kingston, Upper Forrest Farm, Farnanes, who has been farming organically for nearly 20 years.

To farmers thinking of making the switch, he urges them to seriously consider it as he said the industry ‘needs new blood’ and, if you’re operating in the right markets (horticulture, pig, poultry), there is a living to be made.

He started the conversion from conventional to organic farming in 1997, earning his certification in 2000. His motivation for making the change was his belief that conventional farming simply wasn’t sustainable.

As a conventional farmer, his animals were winter finished and, as he now finishes throughout the year, there’s an added bonus of improved cash flow.

But the big change when switching to organic was diversifying from being commodity-focused, to being customer-focused.

That meant that, instead of supplying grain to co-ops or the sugar factory, he sells directly to farmers. When there are surplus oats, he supplies to Flahavans.

He grows a combi crop of wheat, oats and peas; or oats and peas which are used for cattle, sheep, pig and poultry feed. His grain customers come from Cork, Kerry, Clare and Offaly.

He also expanded into growing potatoes as he said ‘business brings business.’

‘Our customers were looking for other things. At one point we also grew vegetables, but it was very labour-intensive so didn’t continue,’ he said.

He grows a blight-resistant early and main crop of potatoes on two and a half acres with customers coming from throughout Cork, including some who supply farmers markets as well as the Quay Co-Op in Cork city.

‘We sell seven tonnes of saleable potatoes per acre, wholesaling at between €1 and €1.50 a kilo. And we sell 1.5 tonnes of grain per acre at an average of €420 a tonne. The price for oats is set by Flahavans which is the benchmark. The remainder of grain we keep for our own 90 to 100 cattle,’ said Stuart.

There was, he said, an original investment needed for the likes of drying and storage facilities, but organic grants are available to help meet these costs.

‘Organic farming isn’t any more labour-intensive than conventional farming; and, in many ways, prices are better.’

He added: ‘For the first two years of conversion, lots of people talk about converting the land, but I think it’s all about converting your mindset.’

And, naturally, he’s learned lessons along the way, some of them expensive.

‘For example, some breeds i.e. Angus, Hereford and Shorthorn are more suitable to the organic system than the continental-type breeds which require meal feeding for finishing. Certain crops, particularly modern barley, don’t suit organic soil either as they’re not designed for weed suppression.

‘On our farm, we live with weeds and manage them. We need them for biodiversity and they actually help with pest control.’

A benefit of organic farming is that grass is less vulnerable to drought. ‘Modern grasses are shallow rooted, but organic and older grasses have deeper roots which are not fed at the soil surface, so a dry year actually suits us on this farm as the soil is also good at retaining moisture.’

He said they get offered one to two organic farms a year from farmers who are retiring, etc and, while there’s no shortage of organic land, there is a poor uptake in people taking it on.

However, Stuart feels there is a good living to be made from organic farming if you’re operating in the right markets and enterprises.

‘There was a big influx of organic famers four or five years ago, but then the Department of Agriculture closed the EU Organic Scheme, which provides support payments, a few years back which stopped new blood. It re-opened last year and a few people got in, but I think new blood is needed.’

The scheme provides payments of €220 a hectare for the first two years when, Stuart explains, you are doing all the good things but get none of the benefits as you’re not yet certified as organic.

Payments are then reduced to €170 a hectare; and are capped at a certain number of hectares.

Everything on Stuart’s arm is 100% traceable.

‘Everything our cattle need comes from our farm in terms of feed and bedding; there are no bought in inputs. And seeds are the only inputs on our grain and potatoes.’

Not surprisingly, this ethos spills into his everyday life. ‘We haven’t used oil to heat our house for 40 years and have a wood burner, run by wood from the farm as well as other waste products. We heat the water from solar panels and we’re considering a plug-in car.’

In terms of expansion, Stuart has entered into a partnership with another organic farmer who will let some of his cattle graze on his land this summer. ‘It’s a better option than renting expensive land,’ he said.

For anyone interested in organics, Stuart says there are plenty of opportunities – they’ve had, for example, enquiries from a London-based business to grow a specific wheat for wheat grass.

----