By Peadar King

The sea is awful big. So, began and ended, what was then called and maybe still is, a composition in my father’s primary school days. It was a story he told over and over. It wasn’t what The Master had expected.

And Lena Daly, my father’s second cousin, who penned the composition, was made to pay the price. What that price was I cannot remember. Most likely ridicule.

But while all other essays from my own primary school years have been erased from my mind, that one remains. It is a mark of a good essay. A century later it has stood the test of time.

In this age of minimalism, it works. A precise, pithy, even epigrammatic statement of fact. But it is also much more than a statement of fact.

It’s a young girl’s view of the world as she stood on the shoreline of West Clare looking out, stretching, stretching beyond the horizon until the sky dips into the sea. Grey blue on grey blue.

The vastness of it all. The immensity of it all. Stretching, stretching across a sea that to her seemed awfully big.

This is existential. Maybe this is what the girl-child felt, what she sought to convey, what The Master could not comprehend.

She, just a speck on the landscape and on the seascape. Her existential moment of awareness. Conveyed in the most striking of sentences. A story all in itself.

If I were a painter, and I am not, it is a scene I think I would visit and revisit. A young girl on a beach. Not as The Romantics have done.

In my imaginary painting there would be no parasols, no long dresses, no deckchairs, no laconic women reclining on serene summer days.

I would paint a diminutive solitary figure facing the sea, watching its yellowed foam from swollen waves crash against jagged shorelines. Fierce lightning flashing across the sky.

Rain pouring down. Above, fretful birds would swoop wrestling with nature’s forces, wrestling the power of the sea. Their spec on the skyscape. Their existential moment.

The girl-child of my father’s school days often comes to mind when I stand by the sea. She was right. From some vantage points, the sea is awful big. A phrase that has clung on. A phrase that won’t let me go. Even here in West Cork. Particularly in West Cork. Toe Head. Dursey Island. Owenahincha beach.Red Strand beach. And there are many many other places stretching from Kinsale to Brow Head, not just the most southerly point in Co Cork but the southern-most point in Ireland.

Places that I have still to discover. Perhaps that is what draws us to the sea on wild winter days.

Spring days, too, with the promise of rising temperatures and for those of us not all year-round swimmers, the thought of the first summer swim.

There is something utterly liberating about sea swimming, the very act of self-immersion. Salt sea water on skin. It is an unambiguously sensuous experience. Most often a communally sensuous experience. A very public sensuous experience.

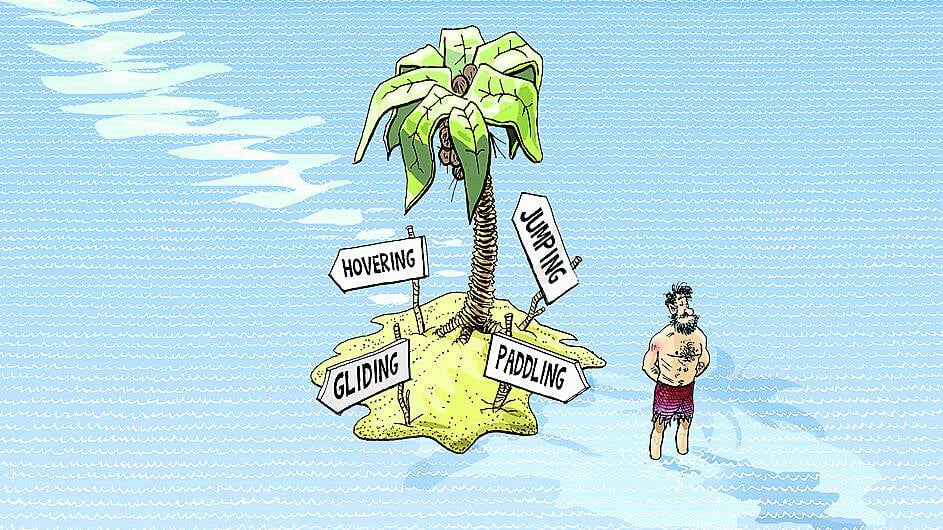

And I am envious of the ease with which some people enter the sea. The gliders. It all seems effortless. Hardly a break in their stride until the sea takes them. Stroking the water gracefully. Cutting through the waves. Then, total immersion only to momentarily disappear beneath its majestic beauty.

I, I regret to say, am a hoverer. Feet, ankles, knees and then I stop. It used not be like this. There was a time when I used to rush to the sea. Now as I stand at the water’s edge, I invariably hesitate. Why, I don’t know. I am not alone. There are other hoverers. Each encouraging the other. ‘It’s not as cold as yesterday.’ ‘As we’ve come this far.’ ‘It’s not so bad when you’re down.’ Stranger conversations at water’s edge. Eventually, we summon up the courage. And we wade in.

Far from the hoverers are the jumpers. Young people for the most part. Mostly clad in the seal-like skin of wetsuits. From the edge of piers they jump. Some run and jump. Exuberance is theirs. As is the sea. Each urging the other on. Jumping sequentially. Jumping in unison. Shrieks of unrelenting joy. And then the big splash. Soul salve.

And all over West Cork, there are ample jump-off points. Some I have gotten to know. Some I have just heard of. Kinsale’s Nohoval Cove. Rosscarbery Pier. Castletownshend’s Middle Quay. Places to go. Places to explore.

For the gliders, the hoverers and the jumpers, it is always the same.

‘You never regret a swim’, my mother used to say. Unusual as it was for her generation of rural women, Mam was a half-decent swimmer. A draconian modesty denied many of her generation of this most sensuous of sensations. Perhaps others, too, but that’s another story.

There is also another sea. The same sea but different. One that holds danger. And death. A place that holds many of its own dead. Refusing to give them up. And West Cork knows that only too well.

Union Hall holds its own monument to the sea’s dead. To stand in front of that monument is sobering. A reminder of lives cruelly cut short. A reminder of loved ones’ grievous loss. And a reminder, too, of our own mortality succinctly summed up by the most sublime of wordsmiths, William Shakespeare.

Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end…

We are but a tiny spec. The sea is awful big.