100 years ago this week, writes Robert Hume, a story dominated the news in Skibbereen – was the man in charge of the workhouse a ‘fit and proper' person for the job?

100 years ago this week, writes Robert Hume, a story dominated the news in Skibbereen – was the man in charge of the workhouse a ‘fit and proper’ person for the job?

SKIBBEREEN’S workhouse is ‘as well managed as any workhouse in Ireland’, claimed Jeremiah Collins, Master of Skibbereen Union Workhouse – though he admitted knowing only three others.

Not everyone agreed.

Local Government Board Inspector, Alfred P. Delaney, bore a personal dislike of Collins – who had been Master since 1906 – and was determined to expose his “gross neglect of duty”.

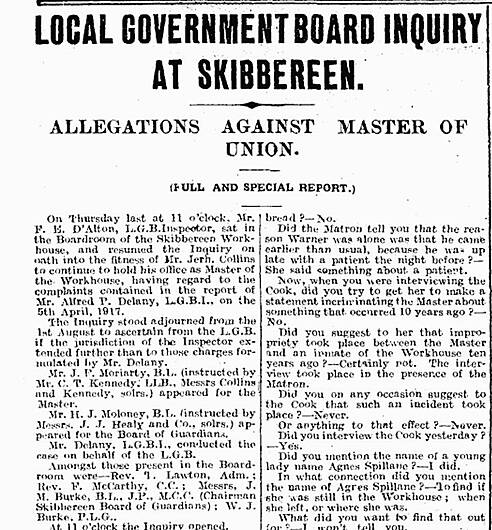

Delaney was both prosecutor and witness in an acrimonious five-day inquiry, held in the workhouse boardroom under the direction of Mr Frank E. D’Alton.

The main charge involved repeated absences. As Master, Collins was responsible for locking the ward doors at 9 p.m., checking male inmates were in bed, and fires and lights extinguished. In practice, he and his van-driver, Tom Herilhy, ‘persistently”’got home after 9 p.m., sometimes as late as 11.30 p.m. ‘I don’t think the Master cares,’ Delaney protested.

Collins countered that he needed to visit his dying brother in Leap; and consult doctors about patients in the workhouse hospital. The schoolmaster, or matron, always covered in his absence.

Chairman of the Guardians, Dr J.M. Burke, acknowledged Collins had permission to visit his brother; and the Doctor confirmed that he transported patients from the hospital.

Frustrated, Delaney began to hurl a series of other recriminations, which had apparently come to his attention during a surprise visit to the workhouse.

He claimed that the workhouse horse and van had been used to drive the Master’s wife to school, though nothing in the porter’s records substantiated this. He also claimed Collins had allowed his sister-in-law accommodation in the workhouse. But this was only so she could look after his sick son. Further, that he had contracted roof work to his friend Callaghan. However, the slater was employed with the Guardians’ full knowledge.

Delaney persisted, like a dog with a bone. One inmate, Jim Warner, had access to the stores where he regularly cut bread for the paupers, and was ‘privileged’ to wear his own coat. In truth, he had been slicing away for 14 years – it saved paying someone else; and he had permission to wear his own coat.

The Master’s sobriety and moral integrity also came under fire. Collins had once had a craving for liquor, but had taken an abstinence pledge in 1915, and witnesses swore he had since been sober. Allegations that he pilfered provisions proved groundless; as did an accusation of inappropriate behaviour with former inmate, Agnes Spillane.

The Chaplains confirmed that Collins performed his duties ‘diligently’, and the Matron, Sister Lorenzo, described him as ‘capable and efficient.’ Dr Burke admitted Collins was not perfect but ‘it would be hard to get a better man.’ Delaney’s malicious slanders and ‘extraordinary spleen’ had got him nowhere. Jeremiah Collins had emerged from the inquiry untainted by complaints of dishonesty and immorality.

‘Was there ever anything more laughable since the dish ran away with the spoon?’ mused The Southern Star.

On November 20th, D’Alton returned his verdict.

The Guardians could not believe their ears, as words such as ‘misconduct’ and ‘constant absence’ rang out again and again.

D’Alton would delay making his final decision for a year, pending further reports. However, if more ‘irregularities’ came to his notice, Master and van-driver would be dismissed immediately.

It was tantamount to saying they were guilty, complained the Guardians.

And who was to monitor their behaviour during this time?

Why, Mr Alfred P Delaney.