On the 42nd anniversary of the Whiddy Island disaster, maritime lawyer Michael Kingston, who lost his father in the tragedy, wonders if we have learned anything since the Bantry explosion

ON July 9th 2020 the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled against Ireland, finding the Department of Transport to be in breach of regulations regarding investigating maritime tragedies.

Under an EU Directive, investigations must be carried out with sufficient maritime competence and by an independent body. The ruling found that the presence of two Transport department civil servants on the State’s five-person Marine Casualty Investigation Board (MCIB) represented an obvious conflict of interest.

This breach, for all Irish seafarers, has fundamentally impacted on their safety, and continues to do so. The main purpose of the MCIB, under international law, is to find out every aspect of an accident in order to make recommendations to prevent it happening again.

Critical to such investigations is the analysis of the regulations surrounding the incident – were they suitable? Could they be improved? Were they correctly enforced?

As all maritime safety regulation is set by the Department of Transport, this effectively means that MCIB Board members have been investigating their own work, and making recommendations to themselves.

Mary Kingston, whose husband Tim lost his life in the 1979 tragedy, in front of the memorial at the Abbey cemetery in Bantry, on the anniversary this year.

Mary Kingston, whose husband Tim lost his life in the 1979 tragedy, in front of the memorial at the Abbey cemetery in Bantry, on the anniversary this year.

Despite the passage of 42 years, this incredible current failing is directly linked to the stark and shocking regulatory failures of the Whiddy Island disaster, the biggest maritime disaster in the history of the Irish State, and one of the worst regulatory failures, on multiple fronts, in world maritime history.

The entire crew of the MV Betelgeuse, 42 French citizens, an English surveyor who had just boarded, as well as seven local Gulf Oil employees, were simply left to die on the offshore jetty, despite a significant window of opportunity of over 25 minutes in which they could, and should, have been rescued.

Laying the wreaths at the momument in the Abbey graveyard in Bantry last week, to mark the anniversary

Laying the wreaths at the momument in the Abbey graveyard in Bantry last week, to mark the anniversary

A small fire commenced on or beside the ship at 12.30am. The jetty crew could not fight it because the watch keeper on duty on Whiddy Island, (responsible for turning the firefighting foam system on and alerting the safety boats) was not at his post.

And they could not get off the jetty because he did not notify the available transfer vessel, 7 minutes away, until he returned to his post at 12.50, by which time the electrical leads to the foam system had been burnt. The tribunal into the disaster found multiple and catastrophic safety failures, including: Gulf Oil removed the bridge to the Island for commercial gain so that two tankers could get in at once; They reduced the firefighting system on the offshore jetty from automatic to manual, placing all responsibility on one human being; Many of the escape facilities to even get into the sea were compromised, such as ladders being guillotined for security concerns; The workers’ hut on the jetty was out of classification and extremely dangerous; Multiple emergency safety lights and hand-held fire extinguishers were not working on the jetty; The fire-fighting tugs, which also acted as escape tugs, were transferred from the jetty to a site 20 minutes away, out of sight, rendering them useless.

In fact, under Gulf Oil’s self-declared operation manual, the fire-fighting safety tugs were supposed to be beside the tanker at all times. These changes contravened Irish domestic law which stipulated that there must be a means of escape for workers and vessel crews at all times.

The Department of Transport was never held accountable by the Tribunal, which instead deflected attention to the behaviour of Gulf Oil, which had forced its employees to lie to the Tribunal in order to change the timelines and shift liability entirely to the tanker, (see Tribunal’s Chapter ‘The Suppression of the Truth’).

No one was held to account, either, for these lies, as perjury charges were inexplicably dismissed in Bantry District Court, despite a tsunami of evidence in the Tribunal from the people of Bantry about when the fire actually started.

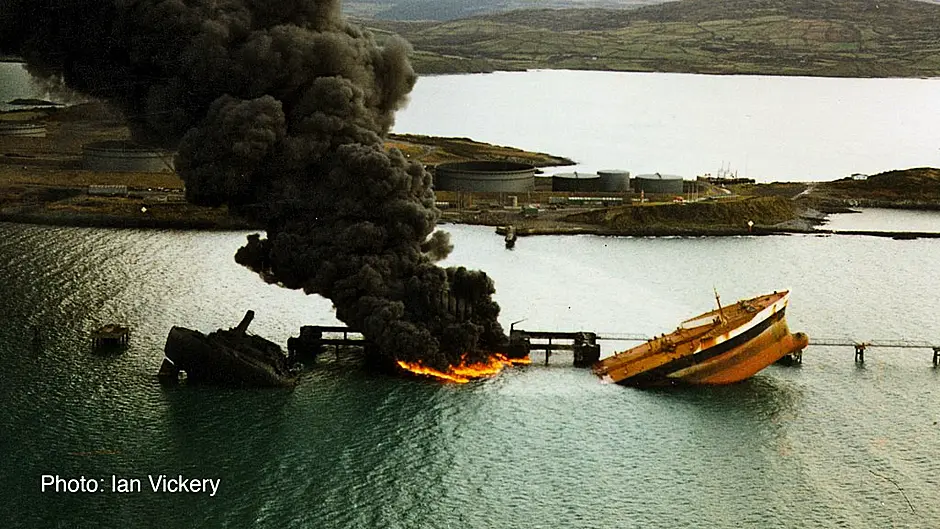

The wreck of the jetty after the French tanker ‘Betelgeuse’ exploded at the Whiddy Island oil terminal on 8th January 1979 with the loss of over 50 lives. Picture: Ian Vickery snr.©

The wreck of the jetty after the French tanker ‘Betelgeuse’ exploded at the Whiddy Island oil terminal on 8th January 1979 with the loss of over 50 lives. Picture: Ian Vickery snr.©

The torturous circus surrounding this failure in the administration of justice diverted the families and their lawyers from the over-arching failing – that Ireland’s regulation and regulatory oversight had failed, that the government departments had allowed all these catastrophic safety reductions in contravention of their own laws.

To make matters worse, the tanker was not carrying a simple gas system to prevent the ultimate explosion, even though it was included in 1974 international regulation – but Ireland had not ratified the convention. The system was employed after the disaster. Despite this, Ireland is still not ratifying multiple further international conventions to enhance safety, as they gather dust on the shelves of the Department of Transport, or they do so incorrectly, as evidenced by the European judgment.

The Transport Department has now asked the Dail to waive pre-legislative scrutiny of the legislative changes they are being forced to make following the European judgment, a highly unusual request.

All legislation needs to be analysed correctly. I have written, with barrister Ciaran McCarthy, to ask the Transport committee of the Oireachtas to resist Minister Eamon Ryan’s request to waive the scrutiny.

I am also in on-going discussions with the National Bureau of Criminal Investigation concerning allegations from multiple whistleblowers that MCIB draft reports were changed and safety recommendations removed.

Let’s hope that in 2021 we can finally enact legislation that is fit for purpose, that will, after 42 years, create a system that gets to the bottom of regulatory failings, so that we learn fully from tragedies and protect our merchant seafarers, pleasure craft users, fishers, and rescue services.

• Michael adds:

This article is dedicated to the memory of Mrs Mary O’Shea, wife of Cornelius O’Shea, whose body was found with my father’s several months after the disaster, to Noreen O’Sulllivan (nee O Leary), daughter of Denis O’Leary, whose body was found in the same place shortly thereafter, and to Mrs Nellie Brennan, mother of victim Charlie Brennan.

All are recently deceased and our thoughts and prayers are with their families.

We also remember Mrs Mary O Shea’s son-in-law, Connie Cronin, who died tragically on January 8th 2021.