In the week when the regional newspapers association, Local Ireland, launched its annual awards scheme to champion local journalism, Peadar King recalls the Skibbereen Eagle’s much-maligned famous editorial

IT has become a much-maligned catchphrase. A kind of laughingstock. The editor of a local West Cork newspaper addressing directly the Tsar of Russia. ‘The Skibbereen Eagle is watching you’, will garner 125,000 searches in 0.5 seconds on a Google search. All of whom ridicule it. For its presumption. For its outlandishness. For its disproportionate sense of one newspaper’s place in the world. For being David in the face of the might of Goliath.

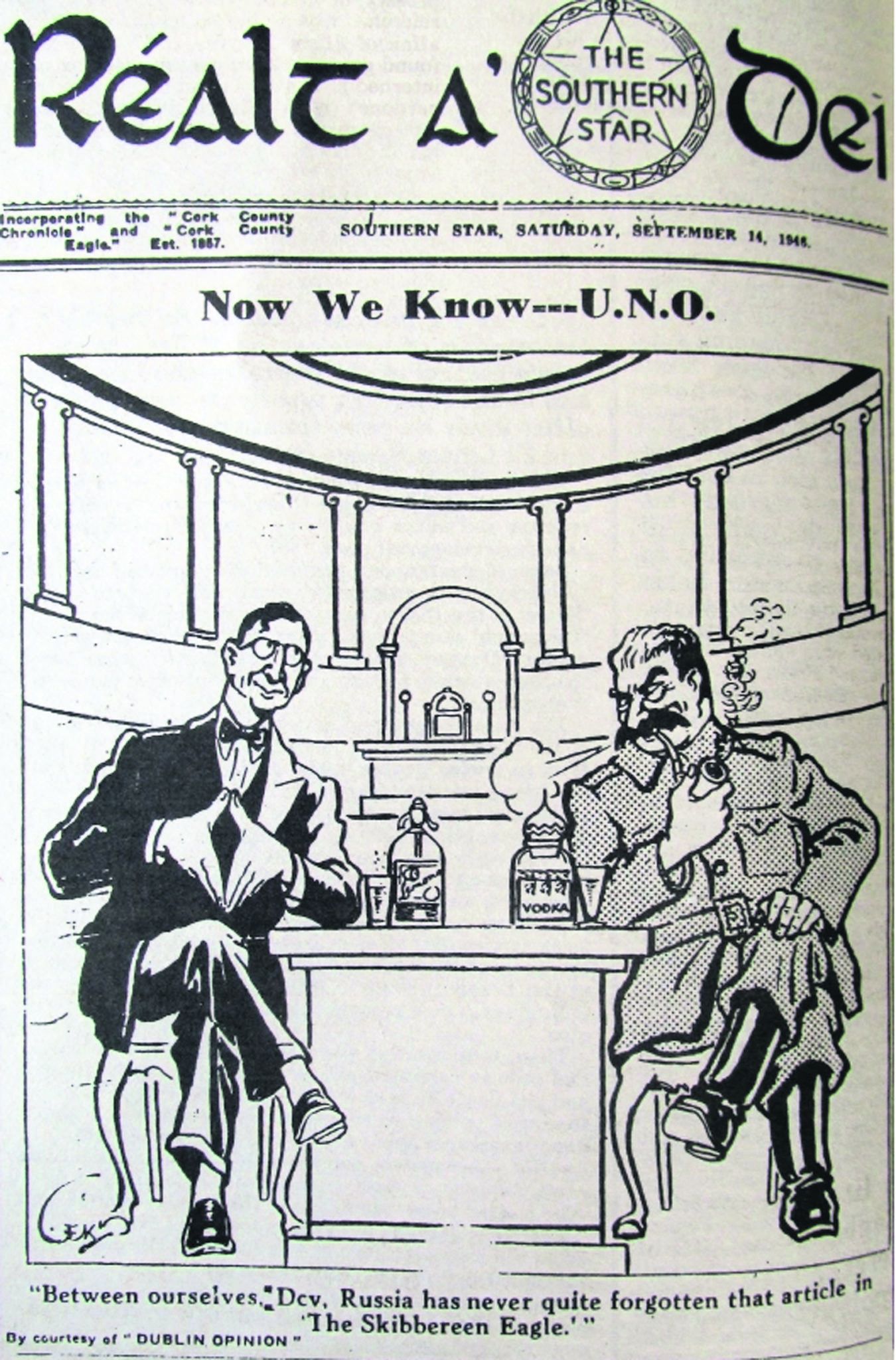

For the record, on September 5th 1898, The Skibbereen Eagle declared its intention to ‘keep its eye on the Emperor of Russia’. A declaration subsequent wags satirically told us must have had Tsar Nicholas II quaking in his boots.

Inadvertently, The Southern Star played a role in The Eagle’s warning of the Tsar. It had just opened its offices and competition was keen not just for readers, the lifeblood of any newspaper, but for commercial sponsorship as well. In all likelihood, there was not sufficient room for two Skibbereen papers at the turn of the 19th century in West Cork. And that is how it transpired. The Star won out over The Eagle. But that’s a well told story and you probably knew that already. But for me this story carries another resonance.

For all the mockery, for all the accusations of grandiosity or grandiloquence to quote one commentator, what I find interesting is the way in which the 100-year plus commentary that has attached itself to this article doubles down, not so much on the content of the article, but on the source. A regional newspaper. A provincial newspaper.

An article if written by The Irish Times or The London Times would not have attracted the same level of derision, the same level of opprobrium.

As if the Tsar of Russia would take into account the views of The Irish Times or indeed The London Times. Not when you have a divine right to rule.

The self-delusional head of the Romanov family with his unswerving belief in his God-given right to rule as he wished was beyond all entreaties or warnings irrespective of their source. He was as likely to heed The Skibbereen Eagle as he was The London Times.

The presumption is that local newspapers will confine themselves to local matters, what are perceived by outsiders to be the ephemera of localized everyday life. For insight into how the world works, the implication runs, we ought to rely on top-down narratives. Other people’s narratives. Those whose lives are far removed from our own. That we become passive recipients of other people’s world views not creators of our own.

This is not an either/or scenario. This is not to suggest that we cut ourselves off from global perspectives, but rather that everybody who wishes to engage with and critically contribute to ideas about the world can do so irrespective of geography, irrespective of professional status, irrespective of sex and gender, irrespective of ethnicity.

And it was these concerns that co-founder of Amnesty International, one-time Irish government minister and Nobel and Lenin peace prize winner Sean McBride considered in a 1979 report for Unesco, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

He predicted a world dominated by a global media, where people would no longer make sense of their own world but would instead be told how to name their own existences.

That prediction has sadly come to pass. We have become passive recipients of other people’s world views and we very often blithely mouth their opinions. McBride urged people to resist this outside imposition and to record and make sense of their own stories. In the century-long opprobrium levelled against The Skibbereen Eagle, I have not seen any account to the effect that celebrated the fact that on the cusp of a new century that would be marked by a level of blood-letting the world had never experienced in its 4.5bn-year history, a small provincial newspaper in a small provincial town on the margins of Europe felt sufficiently engaged with the world to want to confront one of the main protagonists in a conflagration the legacy with which we are still living today.

The fact that it only confronted Russia and not the imperialist self-aggrandisement of neighbouring Britain, something The Skibbereen Eagle must have been more than intimately aware of at the time, is equally telling and of course little commented upon.

In that respect, media reporting has little changed in the last 100 years. Russia remains the bête noire, the country the western world loves to pillory. The one country that can galvanise an international response like no other. The fate of those fleeing western sponsored wars, those left floundering in the seas of southern Europe barely getting a look-in.

Confronting current Russia’s imperialist blood-letting should not preclude us from confronting all the other imperial powers and would-be imperial powers, who are equally culpable of egregious bloodletting. Think of Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan.

The deadly footprint of the United States, China, Britain, France, Saudi Arabia, Turke and the UAE is as evident in these countries as is Russia’s in Ukraine. For the Ukrainians, Europe and the European Union lowered the drawbridges that have locked out so many fleeing war’s destruction beyond Ukrainian’s borders. For those who risk life and limb to escape the horror of war across Africa and the Middle East, the drawbridges remain in place. No people of colour need apply.

In confronting Russian culpability for the mayhem that was about to engulf the world at the start of the 20th century, the Skibbereen Eagle got it half right.

• Local Ireland, the organisation which represents print and online news publishers around the country, has launched its annual awards to celebrate regional journalism. The 2022 Local Ireland Media Awards, which are in their seventh year, will honour the achievements of local journalists, photographers and advertising staff.