Some claim the ambush finally convinced the British that they were fighting an unwinnable military campaign, and not just against bands of ‘thugs and murderers’, writes Daithí Fallon

ON St Patrick’s Day 1921 the West Cork Flying Column of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) were waiting at Shipool near Innishannon to ambush British soldiers travelling from Kinsale.

They received word that the British had left Kinsale but then turned back to barracks.

From that moment, the Column’s commanding officer (O/C) Tom Barry believed the Column’s presence had been betrayed.

On the night of March 18th the Column moved towards Ballyhandle (near Crossbarry), arriving at billets at 1am on the morning of March 19th.

At about 2.30am, the distant buzz of military lorries was heard coming from the direction of Bandon. Reports went immediately to Barry and Liam Deasy (brigade adjutant). The Column was roused and assembled in a field 300 yards to the west of Crossbarry Bridge.

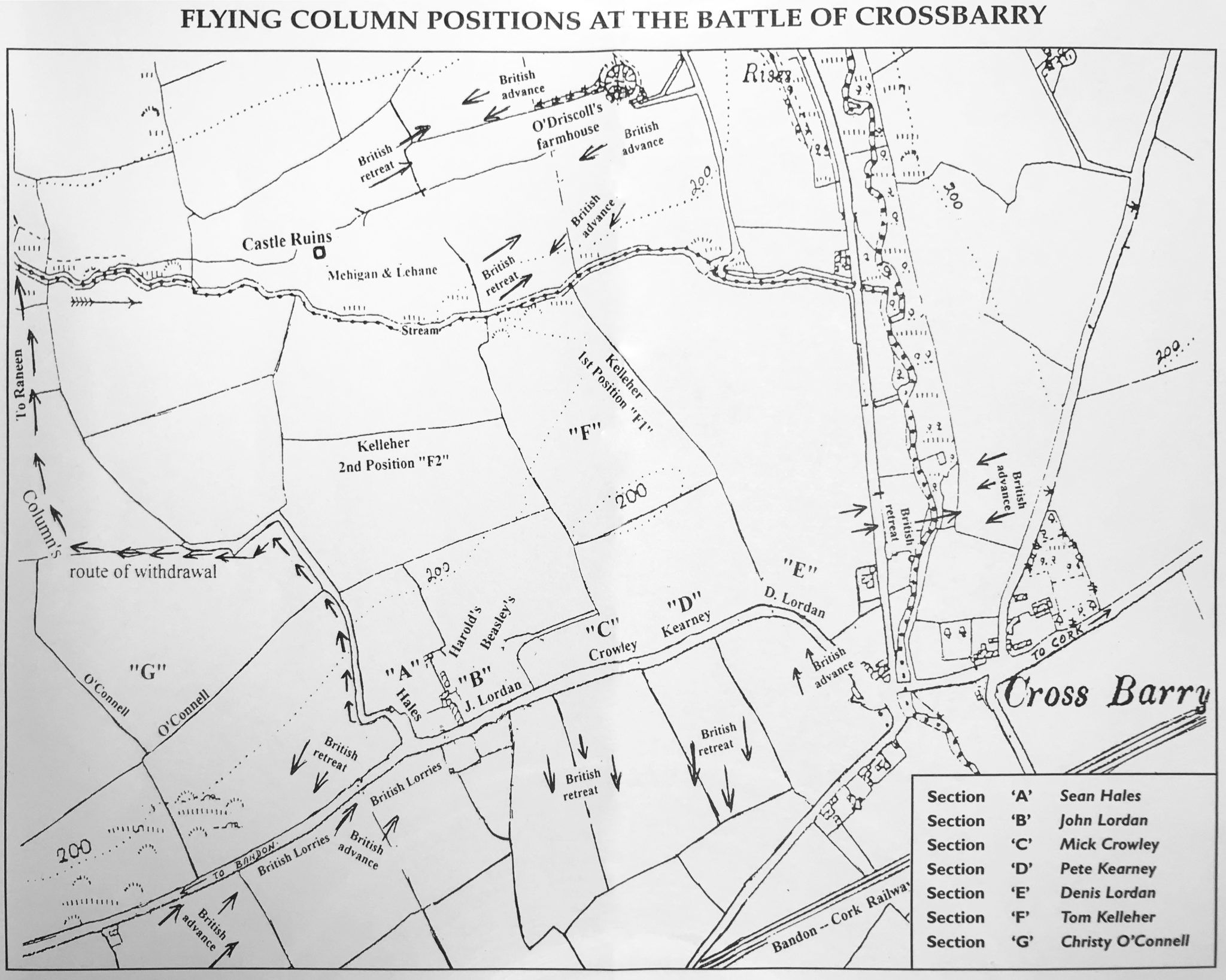

A map of the ambush (copyright Diarmuid Begley)

A map of the ambush (copyright Diarmuid Begley)

The men were already assigned to seven sections of 14 riflemen (See map for section leaders). Sections A to E were placed on the northern side of the Bandon-Crossbarry road, stretching from two farmhouses (Harold’s and Beasley’s) to the bridge at Crossbarry; about 300 yards in all.

Two mines were placed on the road, one each at the western and eastern side of the ambuscade. Section G, under Christy O’Connell, was set up well north of the road, guarding the western flank, with section F, under Tom Kelleher, 600 yards to the rear of the column, on the eastern flank.

The plan was to allow the approaching lorries from Bandon to advance through the ambuscade to Crossbarry Bridge, at which point the western mine would be exploded. Sections A to E would then open fire on the estimated six to nine lorries caught within the ambuscade.

At about 6.30am the Column heard gunshots from the northeast which signalled the death of IRA brigade O/C Charlie Hurley at Forde’s house in Ballymurphy. Hurley had been recuperating from serious wounds received at the disastrous Upton train ambush in February. This also confirmed to the Column that the British were advancing from Crookstown to the northeast.

The advance from Bandon was very slow, as half the occupants of each lorry were on foot at any time, raiding every farmhouse within a four mile radius of Crossbarry. Peter Kearney explained: ‘I can still recall the drone of their engines as they sounded so clearly for a few minutes in the stillness of the morning and then became silent for a similar space of time moving only a few yards at a time.’

Daylight came as the Column waited in silent anticipation. At about 8am the lorries finally arrived. When only three had entered the ambush site, they came to a halt. A volunteer had broken cover early and was seen by the occupants of the leading lorry. Fire was opened immediately at a range of five to 10 yards by sections A, B and C, with the IRA well protected by a high ditch and the farmhouse walls. As the shooting started, Flor Begley struck up his war pipes in Beasley’s yard, as pre-arranged with Barry. The lorries in front of the IRA were quickly routed, and the occupants of the remaining lorries fled back towards Bandon, under fire as they ran.

At this point section G (O’ Connell), on the northwest flank, fought off a section of British soldiers following the lorries on foot, who were attempting to get in behind the main IRA party.

Now shooting was heard at Tom Kelleher’s section (F). Soldiers approaching from Crookstown attempted to cross the fields to attack the main IRA body from the rear. Section F drove back the attacking British as they crossed an open field. Kelleher also sent two riflemen, Dan Mehigan and Con Lehane, to occupy a castle ruin to his northwest. They effectively prevented an attempt by the British to encircle his section from the north.

Next, sections D and E, nearest Crossbarry, came under fire from troops coming from the Cork road to the east and directly south from Innishannon. There was much poorer cover here and it is where the IRA suffered three fatalities. Peter Monahan was fatally wounded having entangled himself in the wires leading from the plunger to the unexploded mine. Both Jeremiah O’Leary and Con Daly also lost their lives here. After several attempts by the British to overcome Lordan’s section, fighting was reduced to only sporadic firing.

Two blows of Tom Barry’s whistle was the signal for the IRA to withdraw. Sections A, B and C withdrew directly north by a lane next to Harold’s farmhouse. Denis Lordan (Section E) went to retrieve the plunger from around Peter Monahan and accidently exploded the mine. This produced enough smoke and debris for D and E sections to get to Harold’s lane and follow the main IRA party.

The column managed to withdraw a few miles northwest while still protecting their rear flanks. Then, with no sign of the British, they turned west, where after several hours marching they could finally rest and eat.

They had managed to survive threatened annihilation by hundreds of British soldiers, but they had also inflicted significant casualties on the enemy, as well as another severe blow to their morale.

Daithí Fallon has lived in Innishannon since 1993. In researching his grandfather’s role in the War of Independence as quartermaster of the South Mayo Brigade, he discovered that guns acquired in England in 1921 by Pat Fallon and Dick Walsh of Balla, Co Mayo were sent by IRA GHQ to the West Cork Brigade.

Crown Forces suffered 10 fatalities

THE fight at Crossbarry was one of the most conventional military engagements of the Irish War of Independence. Several hundred British soldiers left barracks at Cork, Ballincollig, Kinsale and Bandon, though estimates vary from 400 to 1200. The IRA Flying Column was at its largest of the campaign, at 103.

It has been claimed that Crossbarry finally convinced the British Government they were fighting an unwinnable military campaign, and not just bands of ‘thugs and murderers’. Other points are worth noting.

A decision was quickly made by IRA officers to fight, rather than attempt to withdraw. With only 40 rounds of ammunition each, they could not afford a prolonged battle if caught in open countryside. They would have to attempt to surprise the British, break through their lines and enable an orderly withdrawal.

Major Percival, commander of the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment, was amongst the British forces at Crossbarry.

Major Percival, commander of the 1st Battalion of the Essex Regiment, was amongst the British forces at Crossbarry.

During the hour-long battle, the IRA resisted several attempts to outflank them or gain higher ground. Denis Lordan noted: ‘Kelleher’s section put up a splendid fight against a numerically far stronger force of British … (they) undoubtedly saved the Column from being completely surrounded.’

Many of the IRA party had not seen significant action before. When Jim ‘Spud Murphy’ was sent with men to reinforce Kelleher, his orders were to make sure that the inexperienced men were ‘up and firing’.

Whether the British knew of the presence of the column in the area is debatable. In Guerrilla Days in Ireland (1949) Tom Barry claimed the Column’s presence was known and the British round-up was an attempt to encircle it. Other veterans claimed that Crown Forces had learned of the presence of IRA brigade headquarters in the area.

The British tactic of raiding all houses as they advanced slowly, seems consistent with this. Flor Begley said: ‘It just happened that the Column had entered the area during the night, neither the Column [n]or the enemy knowing anything of the moves … of the other.’

In any case, the element of surprise gave the IRA a major advantage against the first lorries arriving from Bandon.

Crown Forces had a habit of overestimating the strength of the Republicans. Mick Crowley recalled that the British ‘made surprisingly poor use of their great numerical superiority.’ Others claimed the wail of Flor Begley’s war pipes unnerved the enemy, making them believe they were faced by a huge force.

Luck also played a part in an action which could have resulted in the destruction of IRA fighting capability in West Cork. A group of British soldiers from Macroom went to the wrong location, leaving the northwest open for the IRA to withdraw.

Finally, there is the question of the number of casualties on both sides. The IRA claimed to have killed more than 30 soldiers. IRA dead were four (including Charlie Hurley). British cabinet minutes say that eight soldiers plus one policemen died. O’Halpin and Ó Corráin, in their book The Dead of The Irish Revolution state that 10 members of the British forces died, the last from his wounds, on March 22nd.