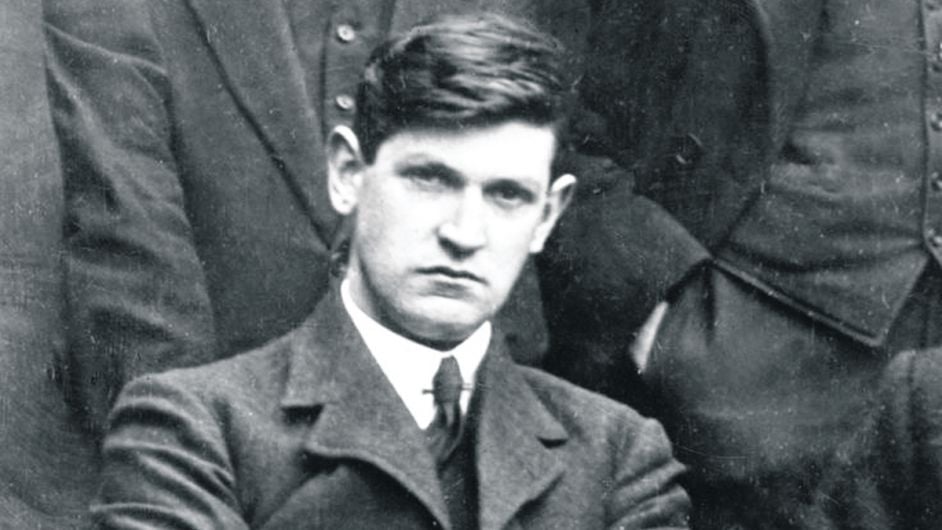

Two men were born within weeks of each other in West Cork, in autumn 1890. They were both named Michael – one Collins and one O’Leary. Historian Sam Kingston explains their juxtaposing stories with very different shades of green

AUTUMN 1890 and in a small farmhouse in West Cork, an Irish hero named Michael is born. No doubt you’re thinking that this boy’s surname is Collins – but in fact he is O’Leary.

Michael O’Leary is a different type of Irish hero; he became a hero of the Great War. Born in Inchigeela in late September 1890, O’Leary is the older of the two Michaels by just three weeks with Collins born on 16th October 1890 at Woodfield, outside Clonakilty. Both men came from rural farming backgrounds. Both their fathers were strong nationalists, active in the land struggle in their own ways.

Both Michaels would follow the same path to a point before diverging quite significantly. These two men highlight the complexity of this era showing two different aspects of Ireland during the revolutionary period.

Life on the land was not an option for either Michael. Both went looking for careers as part of the British Empire. By age 23 O’Leary was a policeman in Canada when he showed bravery by stopping two criminals during an epic gun battle. Collins had moved to London in 1906 for a clerk position in the postal service. By 1913 he was working at a stockbroker. He was also a member of the IRB. The two Michaels were now taking very diverging paths.

Michael O’Leary went on to have a career in Canada and lived into his 70s.

Michael O’Leary went on to have a career in Canada and lived into his 70s.

When the Great War commenced, O’Leary signed up with the Irish Guards. Thousands of Irish men heeded the call to fight. There was strong support for the war effort in Ireland. Collins wasn’t interested. He returned to Dublin in early 1916 to avoid conscription. By then Collins would be well aware of who O’Leary was. He was a national hero.

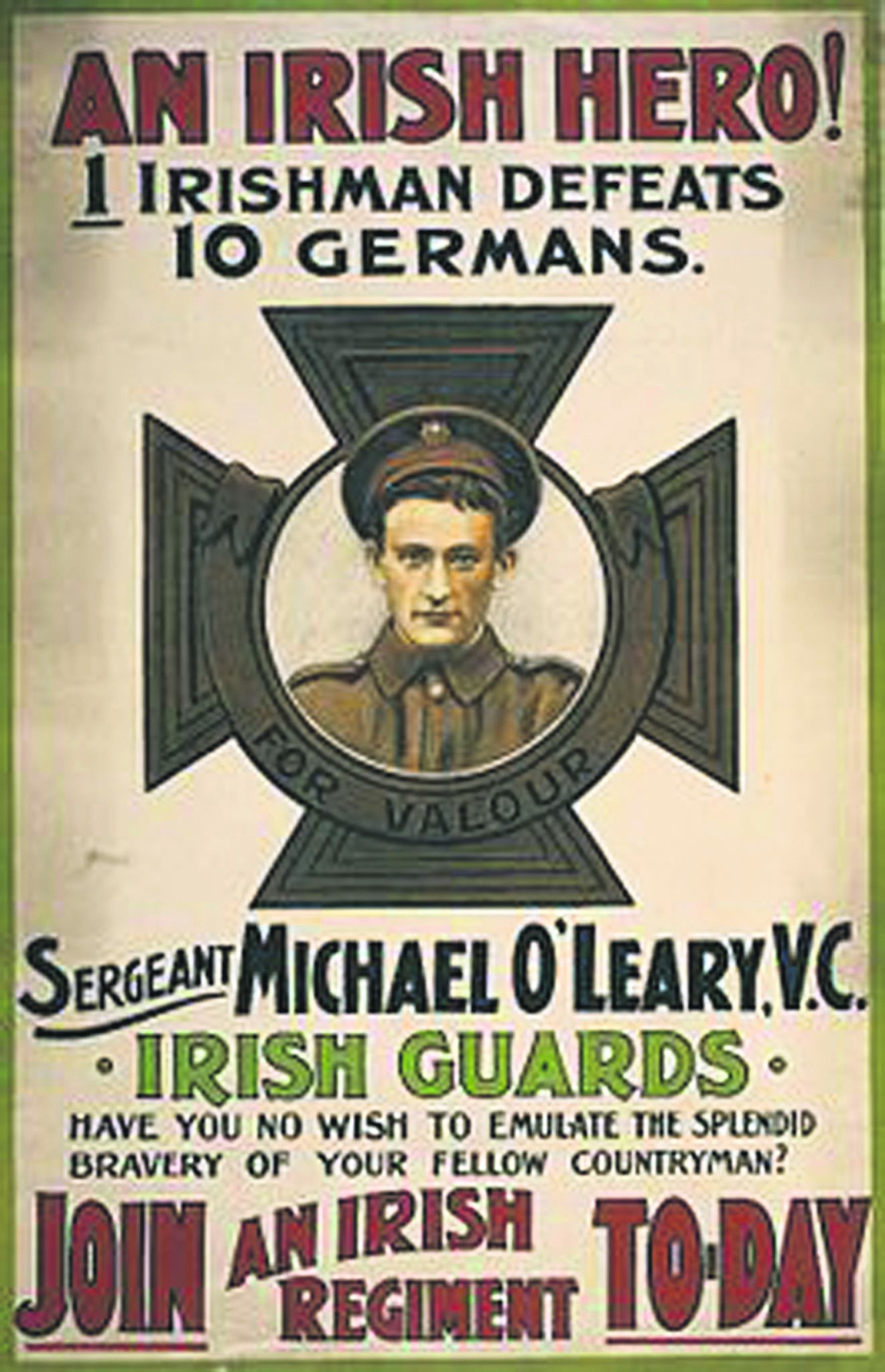

Cuinchy, northern France on February 1st 1915. The Irish Guards are ordered to attack a recently-gained German position. Heavy fire from the German’s position made the attack difficult. Fearless O’Leary singlehandedly killed eight German soldiers, taking another two as prisoners while recapturing the position. This incredible feat of bravery saw him awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest military honour achievable in the British Army. Thirty seven Irishmen were awarded the VC in the Great War but O’Leary would become the most famous.

When O’Leary returned to Cork city to a hero’s welcome, thousands thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of him. He also received a massive turnout in London after King George V presented the award. O’Leary really caught the public attention and he became a media sensation. With his rural Irish background he became the ideal poster boy for the recruitment drive. O’Leary was not a man who wanted the adulation and attention; he didn’t like to speak about his heroics. He was a man of action. In January 1917 he served in the Balkans with the Connaught Rangers. Just over seven months earlier Collins would play a minor role in the Easter Rising as aide-de-camp to Joseph Plunkett.

When the rebels surrendered, they were scolded by the angry locals. With the executions of the Rising leaders, there was a sudden shift in the political atmosphere. The scolding was now for men like O’Leary, soldiers who were previously heroes were now outcasts. Men like Collins became the heroes.

While O’Leary was recruiting Irish men to join the Great War, Collins was busy recruiting to his way of thinking – guerrilla war. Collins was interned in Frongoch in Wales after the Rising and here he started his rise. In 1918 Collins was elected to the West Cork seat for Sinn Féin as they overtook the Irish Parliamentary Party. Ireland had changed irrevocably.

Between Ballyvourney and Ballingeary in July 1918 saw an ambush attack on the RIC. In January 1919 O’Leary married Ballyvourney woman Gretta Hegarty in the local church. That same month the Dáil met for the first time as the War of Independence began to escalate. O’Leary’s home area of West Cork would become a key battleground in the freedom fight. Among those leading the fight nationally was his fellow West Cork man Michael Collins.

For his part, O’Leary (disillusioned with British action in Ireland) resigned from the Army in 1920 and returned to Canada in February 1921. The elusive Collins – as the press portrayed him – was desperately leading the intelligence war, but it seemed the British were getting the upper hand. Shortly after O’Leary left, events such as the Battle of Crossbarry helped swing the war back towards the Irish.

By 1923 O’Leary was working as police sergeant for a railway company. Ireland would still be mourning the loss of Collins, killed in August 1922 during the Civil War.

A recruitment poster featuring O’Leary after he became a ‘hero’ for singlehandedly killing eight German soldiers.

A recruitment poster featuring O’Leary after he became a ‘hero’ for singlehandedly killing eight German soldiers.

O’Leary lived to be seventy, dying in 1961. In between his life fluctuated. He was embroiled in two scandals in Canada, one for bootlegging and the other for smuggling an illegal immigrant. Found innocent on both counts, he still lost his job.

Returning to London, the media attention continued to follow him throughout his life. He worked various jobs, such as making poppies, and as a hotel porter at the Mayfair hotel. He suffered badly from the effects of malaria but still did his duty during World War II. Two of his sons distinguished themselves in the RAF.

In 1954, he was impersonated by a man called Thomas Meagher at a Victoria Cross gathering.

At his funeral, the Irish Guards formed a Guard of Honour and his medals are displayed at their headquarters in London. In 2015 O’Leary was remembered with a plaque in Glasnevin cemetery – also the final resting place of Michael Collins.

These two men were both Irish, both West Cork men from proud nationalist backgrounds. Their lives tell juxtaposing stories, different shades of green. Now 130 years since they were born, we can hopefully reconcile and respect the stories from all perspectives.

• Clonailty native Samuel Kingston is a freelance TV producer and historian