This article originally appeared in our special 2022 supplement marking the centenary of Michael Collins' death – read the full supplement via southernstar.ie/epaper.

His final journey has been the subject of much speculation and intrigue with Collins’ untimely death continuing to spawn numerous conspiracy theories ever since, writes Jamie Murphy.

ON August 22nd 1922 Michael Collins set out from Cork city for a tour, deep into the heart of enemy territory in West Cork.

Collins felt he knew the people of the area he called home and believed he would be safe as the civil war seemed to be coming to an end.

A day visiting Free State National Army posts throughout West Cork and some friends and family was on the itinerary. Little did he know that this would be his last ever visit home.

At about 7.30pm on the return to Cork his convoy was ambushed at a then little-known-place near Béal na Bláth and it was here, at just 31 years old, Michael Collins was killed.

Collins’ final journey has been the subject of much speculation and intrigue with every known detail examined with scrutiny, while his death has continued to spawn numerous conspiracy theories ever since. But what of the facts? Why was Michael Collins in West Cork? Where did he go and who did he see? What actually happened at Béal an Bláth? To get an understanding of this, we need to understand what was happening with the wider story in 1922.

The Irish War of Independence ended in July 1921 after which came the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1922. This divisive agreement allowed for the creation of the Irish Free State, an autonomous government with its own military and police forces but it would remain part of the Commonwealth with the king as the ceremonial head.

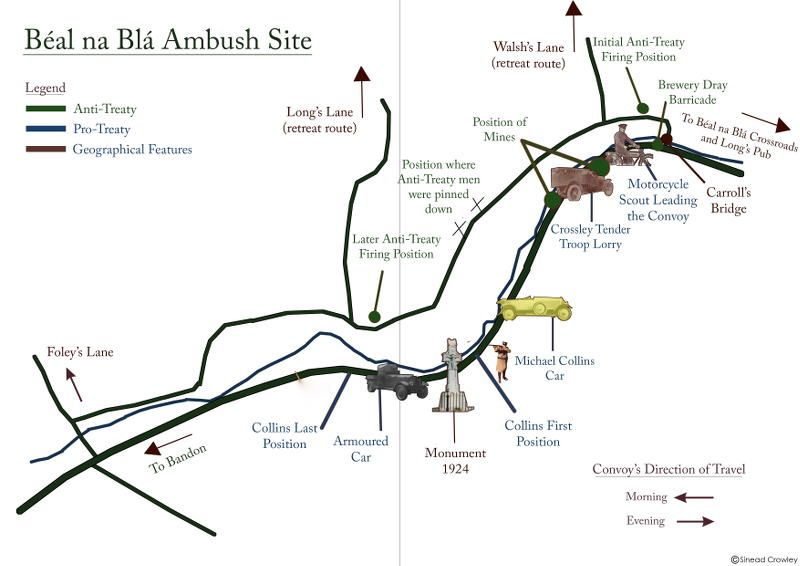

Map: Sinead Crowley & Michael Collins Centre Museum, Castleview.

Map: Sinead Crowley & Michael Collins Centre Museum, Castleview.

It was not everything they fought for, but in Michael Collins’ own words it gave Ireland ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’.

Others disagreed and wanted to continue to fight for a full republic. The Treaty was ratified by a small majority, but this disagreement would eventually escalate to full civil war between the pro-Treaty and anti-Treaty factions in June 1922.

By August 1922 the pro-Treaty Free State forces had taken most of the major towns and cities while the anti-Treaty IRA forces were forced into rural areas and into guerrilla war tactics. One of the last remaining strongholds of anti-Treaty territory was the West Cork and Kerry region. So why did Collins, now acting as commander-in-chief of the Free State forces, choose to visit at this point?

Collins felt he knew the area and the people and as ‘one of their own’, regardless of their differences, he would be safe.

Still an armed convoy was employed for the tour, consisting of a scout rider on motorbike, a Crossley tender that could carry up to 13 soldiers, a buttercup yellow Leyland touring car and a Rolls Royce ‘Whippet’ armoured car – the Slievenamon (now the Sliabh na mBan) – armed with a Vickers machine gun. On the face of it, Collins was travelling to West Cork to inspect the Free State military posts in the major towns across the county, a morale booster for the final push to end the war.

The anti-Treaty forces were scattered and an end to all-out civil war seemed imminent. While in Cork, Collins also met with bank officials in an attempt to secure funds for the new

government, the Minister for Finance seemingly continuing his role. Some claim peace was the purpose of his journey. It is possible.

Collins did meet with individuals that could have been seen as a middleman or a negotiator but, considering the outcome of the journey, these talks either failed or didn’t take place. Certainly evidence from the IRA command at that time suggests they had no intention of making peace.

On August 21st Collins and his party stayed in the Imperial Hotel in Cork City which was serving as the Free State military HQ at the time. The following morning at 6.30am they left for West Cork, first heading westerly towards Coachford and Macroom.

The ambush site is now part of the Michael Collins tourism trail.

The ambush site is now part of the Michael Collins tourism trail.Picture: Alison Miles /OSM PHOTO

From here they travelled via Kilmurry through a little crossroads known as Béal an Bláth. There an anti-Treaty IRA southern command meeting was due to take place in a nearby farmhouse and the large Free State convoy was obviously spotted on passing through, possibly even asking for directions to Bandon.

The IRA meeting went ahead where it was agreed to set an ambush, should the Free State convoy return in that direction. Though it was discussed as a possibility, it is was later told by those involved in the decision that the aim wasn’t specifically to kill Michael Collins, but to challenge the enemy passing through their territory as had been done as part of the guerrilla war in years previous.

Collins continued on his tour while the trap was set for his convoy – a dray cart was left across the road, a mine hidden in the road and somewhere up to fifty armed men waited in the overlooking hillside. Collins travelled to Newcestown, Bandon, Clonakilty, Rosscarbery and Skibbereen before returning back. On the return, he took a detour to Sam’s Cross where he met with family while the rest of the convoy enjoyed a drink in the Four Alls and finally left home for the last time. After a brief stop-off in Bandon they left for Cork city shortly after 6.30pm.

Back at Béal na Bláth the ambushing party had assumed he had returned via a different route and had dispersed. Only a handful remained to dismantle the mine and move the blockade when they were surprised by the convoy’s scout rider. Immediately, they opened fire on the convoy as they retreated along a laneway that runs parallel to the main road and overlooked the convoy.

With the sound of gunfire it is reported Emmet Dalton, Collins’ aide de camp, an experienced soldier and commander of the convoy, ordered the driver to ‘drive like hell’. Here Collins made a vital mistake and told the driver to stop and get out to fight.

The Free State convoy entered cover along the ditch while the armoured car’s machine gun pinned down the anti-Treaty IRA volunteers.

Collins is thought to have moved further down the road and possibly out of cover at this point when the machine gun jammed. This gave the volunteers on the hill the chance to escape and return some fire. Now Collins was left out of position, in open view, without any covering fire. A single gunshot wound to the head and the commander-in-chief fell, dying almost immediately.

Many biographers agree Sonny O’Neill was the man who pulled the trigger, though others dispute this. A ricochet bullet, friendly fire, a hidden sniper, a purposeful assassination by any number of different people or groups, are all the theories we hear today.

Most likely, there is no hidden agenda and Collins’ death is as it’s told, killed in action in an ambush – beyond conjecture there is little evidence to suggest otherwise.

Collins was a young, handsome and charismatic leader. To lose someone of his stature under such circumstances is hard to accept.

In some ways the intrigue into his death and the division it creates overshadows his life and his achievements.

In the end, the ‘who done it’ element is not important; the outcome is the same.

On August 22nd 1922 Ireland lost one of its most influential leaders of the period who helped create the modern Irish State that we know today.