BY ANN HAIGH

Here in West Cork we should never take for granted our ability to head to the coast on a calm summer’s evening and gaze out over the flat blue expanse of the Atlantic Ocean. This is so peaceful and beautiful and the water stretches out as far as the eye can see. When the ocean is still and flat like this, it might appear like the sea is inert and dormant but there is always a multitude of life and activity hidden below the surface.

Taking just seaweed into account, according to the National Biodiversity Data Centre there are at least 570 species in Irish waters. Seaweeds are not true plants but are algae, macroalgae to be precise. They are however ‘plant-like’ in that they get their energy from photosynthesis, extracting carbon dioxide from seawater and using water and sunlight to turn it into sugars and oxygen.

Benefits of seaweeds

Capturing carbon from the atmosphere and ocean is vital to regulate seawater pH and helps to reduce acidification. Importantly a high proportion of the carbon captured by seaweed is sequestered and locked away in the seabed once the seaweed dies and sinks. The oxygen released through photosynthesis provides vital dissolved oxygen available for the respiration of many marine species and it is not just dissolved oxygen that seaweed provides. It is thought that approximately 70% of our atmospheric oxygen comes from production by seaweed and the planetary benefits of seaweed do not stop there.

Star ascidian living on kelp.

Star ascidian living on kelp.

Seaweeds are a food source for many marine species and provide vital habitat. They help to purify water by removing pollutants such as heavy metals and various chemicals. Like plants, seaweeds utilise nutrients such as phosphates and nitrates as their own ‘fertiliser’ and thereby help to remove these from the water and reduce harmful coastal eutrophication (nutrient excess). The presence of healthy seaweed beds around our coastline also dampens the force of waves and helps to protect against coastal erosion.

Seaweed uses

While seaweed is part of our local biodiversity and has a vital role in the marine ecosystem, responsible seaweed aquaculture also provides ingredients for cosmetics and food. It is likely many of us have eaten seaweed products in the last week without even realising. Carrageenan is an additive derived from seaweed which is used as a thickener in a multitude of products including chocolate, ice-cream, toothpaste, and processed meats. The potential to use seaweed as a biofuel, an alternative to fossil fuels, is an ongoing exploration as is using it to replace some agricultural fertilisers.

There are even seaweed supplements available for cows, which reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Native kelp

There are three groups of seaweed in Ireland; green, red and brown seaweeds. Examples include sea lettuce, a green seaweed, Irish moss; a red seaweed and kelp which is a group of brown seaweeds. Our most common native kelp seaweeds in Ireland are oar weed, cuvie, sugar kelp, golden kelp and dabberlocks. Kelp forms beautiful undulating underwater forests, with each alga attached to the seabed by an anchor known as a holdfast. Kelp grows rapidly as it gravitates towards the sunlight at the surface. Kelp forests are one of the most biodiverse and productive marine ecosystems. Crabs, prawns, urchins, sea stars and other invertebrates make their home there and they act as nurseries for many fish species.

Munching limpets

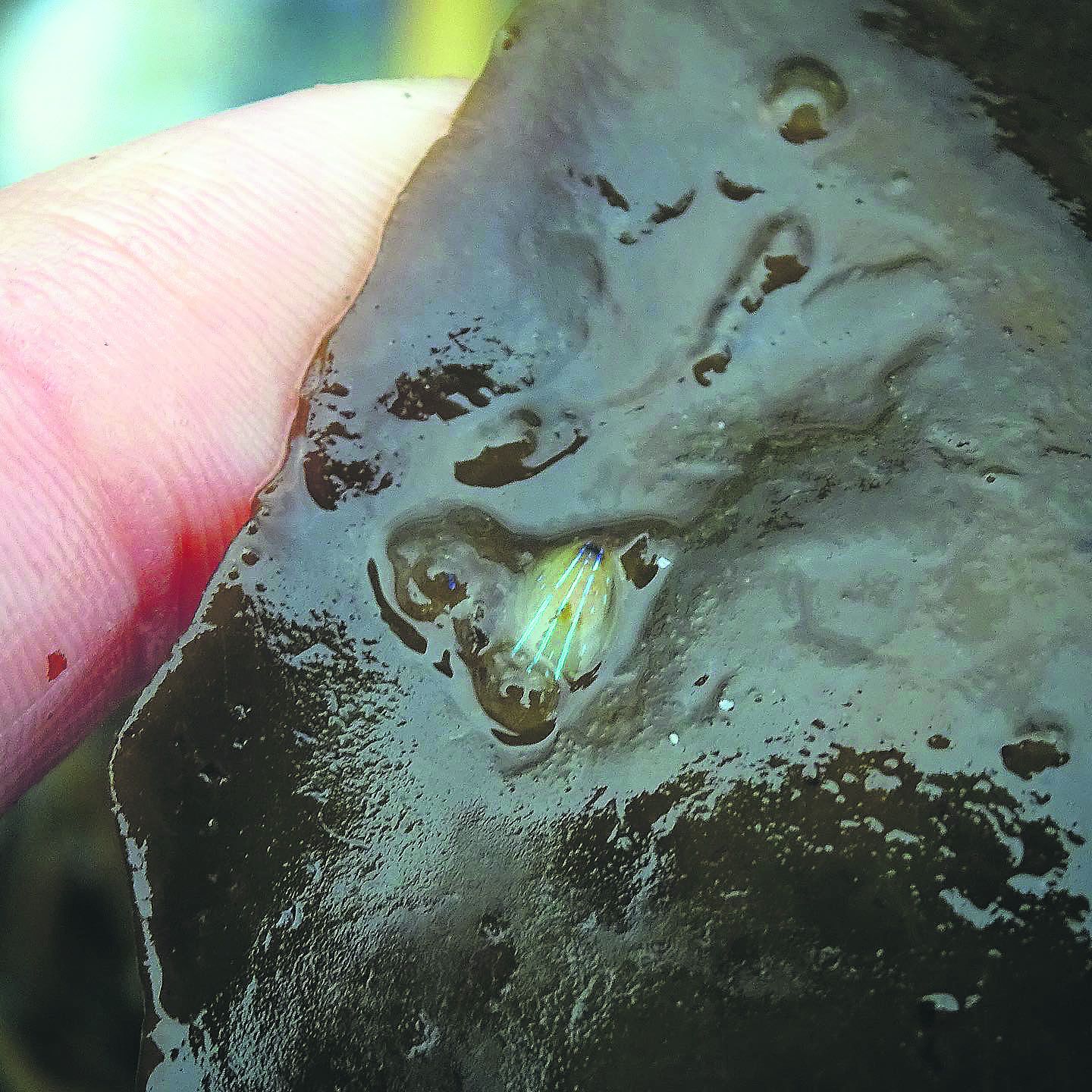

One of the species that depends on kelp is the blue-rayed limpet. These limpets, unlike their relatives further up the shore clamped on rocks, attach to living kelp seaweed and embed themselves into the blade of the kelp as they feed on it.

Blue-rayed limpet showing the typical colour pattern, feeding on kelp.

Blue-rayed limpet showing the typical colour pattern, feeding on kelp.

The limpets can grow up to 2cm long and as they grow, they develop fabulous bright blue lines (see photo); which give them their name. In autumn, and as the limpets mature, they migrate down the kelp stalk to take shelter in the holdfasts that anchor the blades of kelp to rocks and the seabed (see photo);. They excavate a depression in the holdfasts and they often weaken the attachment allowing the kelp to be set adrift and ending up washed ashore.

Somewhere to live

While some animals gravitate to seaweed for food, others come just for somewhere to live. If you have ever looked closely at washed up seaweed you might have noticed strange lace-like patterns of growth (see photo);. This is sea mat, which is a bryozoan. Each tiny rectangle or oval cell houses an individual known as a zooid. Each individual produces a hard skeleton around itself, made of calcium carbonate. This is what makes the white lace like patterns. Each zooid filters the sea water for food, surviving on phytoplankton.

Sea mat (Electra pilosa) attached to seaweed.

Sea mat (Electra pilosa) attached to seaweed.

Another beautiful and remarkable creature which can choose to live on kelp is star ascidian, a type of sea squirt (see photo);. Again, this animal is actually a colony of individuals co-operating. They form colourful flower or star shaped arrangements and making up each ‘flower’ is usually 3-12 individuals. They arrange themselves so that there is a common opening in the middle, the cloaca, through which they excrete their waste. Each individual filters sea water to extract oxygen and nutrients. Bizarrely, star ascidian is one of our closest invertebrate relatives and for that reason they are used in studies to inform human immunology and regenerative medicine.

See the positives

The benefits of seaweed to wildlife are not limited to living seaweed. When seaweed detaches, dies and washes up on the shore, it continues to provide. A network of invertebrates, such as sand hoppers and sea slaters, feed on it and help to decompose it. This attracts birds which feed on the invertebrates. We often see groups of choughs on the upper shore, picking through the seaweed looking for nutritious morsels.

The moral of the story is that we should not moan when we find washed up seaweed on the shore. Granted it may smell as it decomposes and provides the ‘yuck’ factor for some, but it is a sign of this natural wonder providing a vital service to the planet and biodiversity, both in the ocean and out of it.

• Ann Haigh VB MSc MRCVS is a Skibbereen resident, a mum of two, and a verterinarian with a master’s degree in wildlife and conservation.

She is passionate about biodiversity and nature.