TO the surprise of many — director Colm Bairéad included — Irish-language film An Cailín Ciúin was this week nominated for an Oscar for Best International Film.

It's the first time any film as Gaeilge has been nominated, beating out the internationally popular Decision to Leave by the acclaimed Park Chan-wook to the final spot on the list.

It's a film that has received critical plaudits and broken box-office records for Irish-language films, and it's also back in Irish cinemas for another few weeks.

Adapted from the popular short story Foster by Claire Keegan, An Cailín Ciúin is the story of Cáit, a shy child who is sent away from her dysfunctional family for a summer to live with some distant relatives, Eibhlin and her husband Seán.

Cáit's home life — punctuated by a mean father, unsympathetic sisters and a mother at her wit's end — has left her withdrawn and convinced that everything around her is her own fault.

On the long drive from her house to what will become her home, Cáit's father begins to show her some warmth. He's put a bet on Waterford to beat Limerick.

'That's where we are going,' Cáit says.

'Sure isn't that why I bet on them, for luck,' comes the reply.

Moments later, Limerick score a goal, the cursing begins and somehow Waterford's leaky defence is Cáit's fault as well.

They arrive at Eibhlin and Seán's house, which is bigger, cleaner and much quieter than Cáit's own.

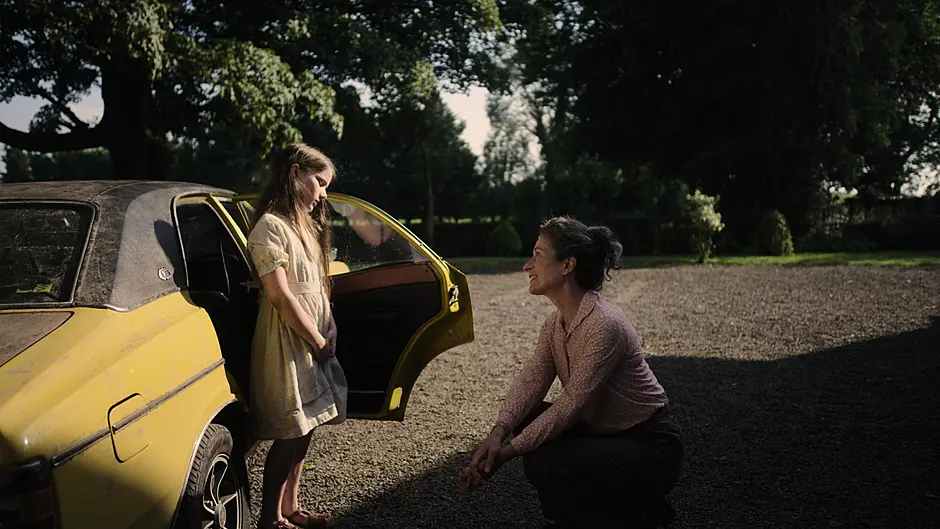

The difference in atmosphere is immediately noticeable. While Seán and Cáit's father do that male thing of standing around unsure of what to think, when to say it and how to articulate it, Eibhlin takes Cáit inside and shows her around.

They prepare lunch — a feast for Cáit's sore eyes — and once finished, Cáit's father rushes out the door, carelessly taking her suitcase and clothes with him.

Most of what happens in the film is slow, almost methodical. The camera lingers on Cait's face for longer than you might expect. Dialogue is kept to a minimum and Cáit's stare is used to say a lot when she feels like she can't say anything at all.

Director Colm Bairéad uses the softest of touches to slowly draw us into what at first feels like a relatively tame story.

Used to keeping secrets from her family, Cáit is told in no uncertain terms that there is no such thing as secrets in her new home.

However, a month into her stay she discovers one that has been kept from her since she arrived. It's a revelation that comes not necessarily as a surprise to the attentive viewer, but one that completely changes the complexion of the film.

Small moments are suddenly given a new weight. A biscuit left on a table, a raised voice, a slow look.

They all become more meaningful as the film progresses until we reach a point where you feel the emotion that Cáit (along with every other character) has pushed away come rushing through you.

Bairéad gives his actors the space and time they need to deliver, which brings wonderful performances from Carrie Crowley and Andrew Bennett as Eibhlin and Seán respectively, but it's Catherine Clinch who truly stars as Cáit.

The restraint she shows throughout looks like the work of an experienced actor as she shines again in those little moments: an outstretched hand, a smile as she runs, a long-anticipated hug.

Another Irish film — The Banshees of Inisherin — is set to dominate the Oscars this year with a record nine nominations. It's a great film and worthy of the recognition, but critics of director Martin McDonagh point to the fact his depiction of Ireland can often fall into a pastiche, that it can often feel a little more like a parody of Irishness even if done well.

An Cailín Ciúin is the remedy to any of those problems, and in truth is among the best Irish films ever made.

To get an Oscar nomination for such a 'small' film is an incredible feat for the team behind the film, but its legacy deserves to be more than just a name among many.