A NEW book by an Irish author provides a detailed portrait of a man often said to be Ireland’s greatest writer of prose in modern times, and gives an insight into his West Cork friend.

John McGahern famously lost his job as a teacher in Belgrove Primary School in Clontarf for writing what was seen at the time as a ‘dirty’ book, The Dark. It subsequently came to be hailed as a masterpiece.

He had also married a woman in a registry office by this time, which turned him into a ‘hopeless case’ as far as his union was concerned.

Now, in a new book by author Aubrey Malone, it is revealed that one of his best friends in Belgrove was fellow teacher Donncha O Céileachair, born in Cúil Aodha, whom he described as ‘a very charming man.’

Donncha wrote mainly in Gaelic. By the time McGahern met him, he’d written a book of short stories with his sister. ‘It was generally believed,’ McGahern said, ‘that he was the only Gaelic writer of distinction or promise among those who were still young.’

McGahern was just starting to work in this genre and was interested in anything Donncha had to say about it. They often chatted in the playground of the school. Such conversations provided a welcome relief to McGahern from what he saw as the often-boring talk about teaching methods that went on in the staffroom.

Donncha once attended a course in Cúil Aodha given by Daniel Corkery on how to write stories. Corkery was born in Macroom. Donncha had known him as a boy. In fact, he dedicated his first book to him.

Corkery’s writing was admired by McGahern as well as Donncha. Donncha also liked the stories of Frank O’Connor. McGahern admired them, but sought a new language in his work that would be more in keeping with the generation that was growing up around him, one that sought to rebel against the old verities.

Donncha also collaborated with Tomas De Bhaldraithe on an Irish-English dictionary that became a kind of ‘bible’ for scholars. He encouraged McGahern to write to an author called Michael McLaverty whose work he also enjoyed.

McLaverty was teaching in Belfast at the time. Donncha was interested in translating his work into Gaelic. He encouraged McGahern to go to Belfast to talk to him about this possibility. McGahern was of two minds about this but he still took Donncha’s advice. He went on to have a lengthy friendship with McLaverty.

McGahern’s first novel was The Barracks. When he was in London talking to his publishers about it in the summer of 1960, Donncha died suddenly of a polio-related illness. He was only 42. McGahern was shocked. His death affected him so much he stopped writing. ‘A sense of futility sucks away all my energy,’ he wrote to another friend of his. ‘There is no will to work.’

Things were never the same for him at Belgrove after that. It’s even arguable that Donncha’s death made him so uninterested in his job afterwards that he embarked on the book and marriage that ended it.

It also made him uninterested in translations of books into Irish.

Now that Donncha was dead, he wrote to McLaverty: ‘The whole Gaelic business looks even more quixotic to me than it was before.’

After he was sacked, McGahern left Ireland to eke out a living teaching in the often-tough schools of East London. The breakdown of his marriage to the Finnish theatre director Anniki Laaksi soon followed.

The two events might have crippled lesser men but, as was the case when he lost his beloved mother to cancer as a 10-year-old boy, somehow he found a way to go on.

After returning to Ireland in the early seventies, he went on to write many books, combining the life of a Leitrim farmer with his increasingly popular novels and books of stories.

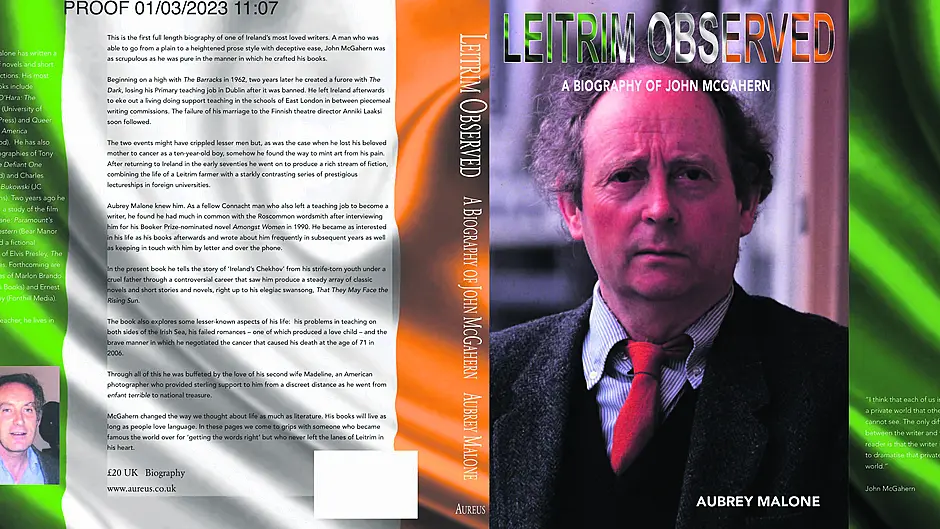

Aubrey Malone knew him. In his biography, the first to be written of McGahern, he tells the story of ‘Ireland’s Chekhov’ from his strife-torn youth under a cruel father, through a controversial career that saw him produce a steady stream of classic novels and short stories and novels, right up to his elegiac swansong, That They May Face the Rising Sun.

The book also explores some lesser-known aspects of his life: his problems in teaching on both sides of the Irish Sea, his failed romances – one of which produced a love child – and the brave manner in which he negotiated the cancer that caused his death at the age of 71.

• Leitrim Observed, (below) published by Aureus Press, by Aubrey Malone, is available from O’Mahony’s and Waterstones in Ireland and Gardners distributors in the UK.