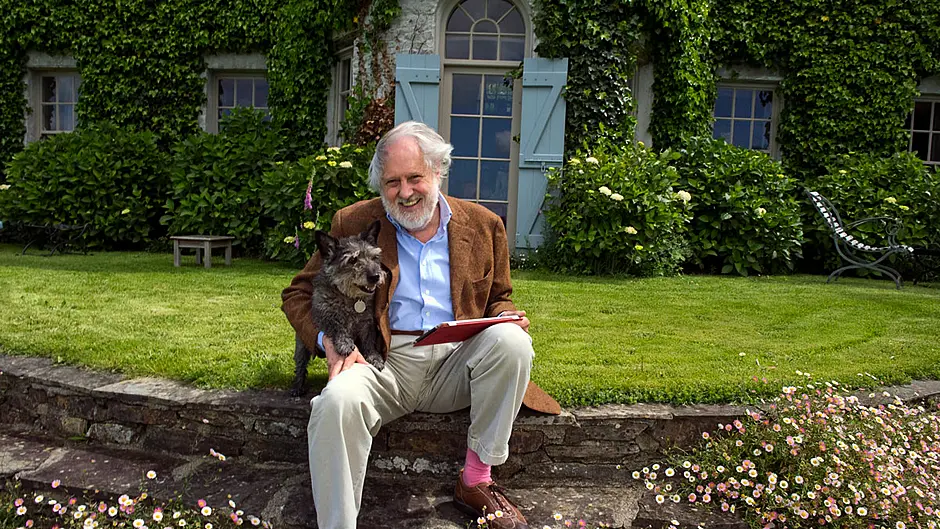

AT the age of 80, Lord David Puttnam is comfortable in his own skin, comfortable in Skibbereen, and comfortable too sharing lockdown with his wife of almost 60 years, Patsy.

In a whistle-stop run through the last eight decades, David describes how being ‘a war baby’ helped to shape him as a slim, energetic person.

He said the relative privation a child’s diet was very carefully worked out during the war, so, by the age of seven, his body was in good nick.

‘It was what we didn’t have,’ said David. ‘The diet contained no chocolate, no fizzy drinks. We got two ounces of butter a week and concentrated orange juice.’

By the time he finished his teens, he was a slim, fit, healthy guy. Today, he says, he weighs 144lbs, just 6lbs above his teenage 138lbs frame.

He never developed a taste for sweets, never smoked, and drinks moderately. He and Patsy eat well, he said, and Patsy is a good cook.

‘I have always had a lot of energy. It is what has driven me. I had to use energy to make up for brain-power because I’m not very clever,’ he says with his trademark wide-grin.

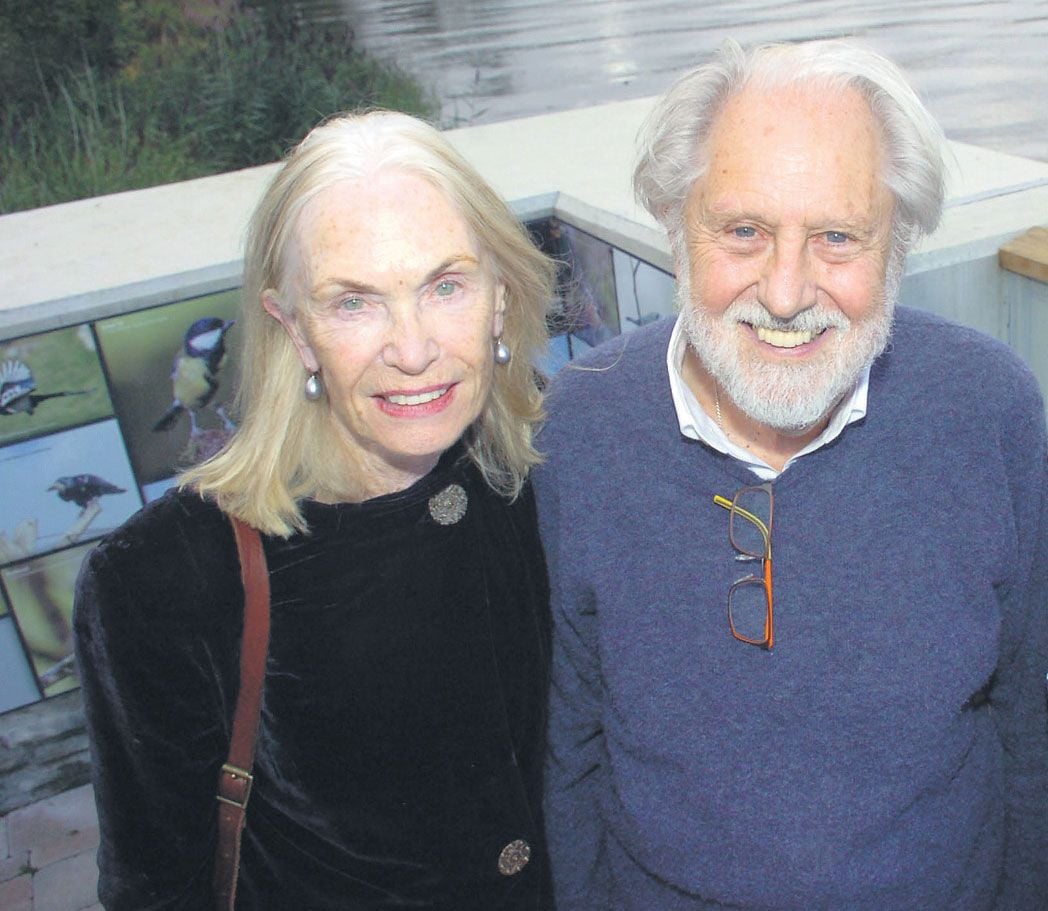

With his wife of 60 years Patsy

With his wife of 60 years Patsy

‘In all honesty, I don’t feel one whit different from when I was 60. Not at all – not in terms of energy, or interest. Not in terms of things I want to get done.’

At 16, he fled school. He hated it. The exception was the affection he had for his history teacher – a teacher who instilled in him a passion for the subject. That same teacher was David’s inspiration for establishing a teaching awards programme in later years.

As a teenager, David worked as a messenger in a publishing house, before switching to an advertising agency.

The real discovery at this time, according to David, was that he loved work, loved earning a living.

David met his future wife, Patsy, when he was 16. They started going out when he was 18, and married when he was 20, so before the age of 21, ‘the foundation stone of my life was set.’

David described his 20s as ‘a rollercoaster.’ He left advertising to set up his own business as an agent for photographers and worked that into becoming a film producer.

At 30, he produced his first film and spent that rest of that decade making whatever movies he could. Fresh into his fourth decade, David won an Oscar for Chariots of Fire.

It gave him confidence and turbo-charged his career. It also gave David and Patsy an opportunity to swap London life for rural West Cork.

A pivotal moment came within a week of winning the Oscar. He was in Scotland to film Local Hero and found himself in a field having an argument with a farmer about access to a beach through one of his fields.

‘It was an amazing grounding experience. It was a very modest film. It wasn’t an acceleration,’ said David. While making that movie, the quintessential city boy ‘fell in love with being in a small community.’

They purchased a beautiful home on the banks of the Ilen River and used it as their summer home for about five years before relocating full-time about 30 years ago.

David confessed: ‘I feel more comfortable here than anywhere else in the world. We’ve made it our home.’

It sounds idyllic, but David said he and Patsy once worked out that he had been away for 20 of their 60 years. It was Patsy, he said, who has done all the ‘heavy lifting’ in their relationship and family life.

Five times in his life, David decided to change course in his career. It was done with Patsy’s backing. In life and in your career, he suggests it’s best to ‘trust yourself, or marry someone who trusts you.

‘One of the reasons I have loved lockdown,’ he added, ‘is that we have been together – for the first time in our lives – for almost a year. It’s been great. We haven’t had a single row. It has been amazing.’

Today, as an educator, teaching in six universities around the world, David works to ‘infuse and develop the confidence’ in his students.

‘I persuade them that they are the messengers. I persuade them that the best chance of the world coming out of its nose dive at the moment is the stories they tell, the messages they bring, and their own commitment to something that is better.’

He turns the myth – “There is nothing new under the sun” – on its head, saying, ‘A lot of people come into the media world thinking that every idea that has ever been thought has already been thought of, and that there is nothing new, which is absolutely untrue. The un-invented, the uncreated, is a vast area, much bigger than the one that has been created.’

Telling true, authentic stories is evident in his life’s work. ‘In every film I have ever made, as a producer, I have managed to inject – to greater or lesser degree – my own story,’ he said.

A scene from his Oscar winning film Chariots of Fire, released in 1981.

A scene from his Oscar winning film Chariots of Fire, released in 1981.

Chariots of Fire, for example, is about the duality in himself – the idealism and the drive.

‘The idea is that good guys can win,’ said David, who delights in the fact that it is President Joe Biden’s favourite film.

‘It gives a lie to the Trumpian version of the world, which is that good guys come last. In Chariots of Fire, they do the right thing and win.’

Looking to the future, David discusses the delicate and difficult balance of what he calls ‘tourism versus liveability’ in places like West Cork.

‘That balance is going to be made more difficult by the post-Covid economy that we try and create for ourselves,’ he said.

According to David, a founding principle of future development has to be shaped by people who are ‘wholly obsessed by the consumer experience.’

Here, he is back on familiar ground – the triumvirate of ‘story’, being ‘authentic,’ and striving for ‘balance,’ when it comes to service and product provision.

The late Steve Jobs and John Field of SuperValu in Skibbereen are cited as two exemplars. He said Jobs is a classic example of someone who was obsessed with the consumer experience.

Field’s supermarket has that too, said David, because ‘the staff always give people the feeling that you are the only person that has called that hour. It’s a miracle, but that doesn’t happen by accident. That is the culture John Field has created.’

Taking agri-tech and the productivity of soil as one example of where Skibbereen, and its Ludgate hub, could become a global leader, David said, here, it is possible to teach people about yield, productivity and healthy food.

‘I am very conscious of the diminished lives our children and grandchildren are going to live as a result of climate change, and the way we can reverse at least some of that by taking care of what we have here.’