Ballinascarthy farmer Vivian Buttimer will complete his term at the helm of Milk Quality Ireland in 2025. He spoke to TOMMY MOYLES

‘I would advise any farmer, male or female to consider putting their name forward for a role on their local co-op board. Young and old, everyone has something to offer, they mightn’t realise it but you always see there’s a freshness when new board members come on board.’

That’s the view of Ballinascarthy farmer, Vivian Buttimer who in early 2025 will have completed his term as chairman of Milk Quality Ireland and with it almost a decade of serving on co-op boards or national committees of the IFA will come to an end.

Earlier this summer he completed his time on the board of Lisavaird after eight years. He represented them on the ICOS (Irish Co-operative Organisation Society) dairy committee, sitting on the seat shared by Lisavaird and Bandon Co-ops. In his time with ICOS, Vivian served as chairman of Milk Quality Ireland for three years, spent a year on the TB forum, and two years as a director.

Until 2018, he was also on the national liquid milk committee on IFA.

‘I got a great education on any of the boards I was on. You’d see the inside of how co-ops work and the day-to-day bits of the business you mightn’t think of. Each of the four West Cork co-ops are so diverse now, it’s not just milk processing anymore so you really pick up skills that you can use on your own farms. Things like being strict on costs, and the day-to-day running costs as well.’

Finding time to be involved in the local co-op can be difficult for many farmers but Vivian said: ‘You made time for it. It was stuff I was interested in but it needed a bit of juggling the farm to make it all work. Family stepped up so the farm wasn’t neglected. My son, Evan, he graduated from the UCD dairy course in 2018 and is in a partnership on the farm with me. My wife, Jocelyn, she works off-farm three days a week but is great cover too. A lot of the board work was east of me so I was able to check the farm in Carrigaline where the beef cattle are too. We just got into a routine.’

Dealing with the changes to the Nitrates Derogation was the hardest part, he recalled, and a lot of time and work went into getting the message across of its importance to farmers and politicians alike. A public campaign kicked off in June 2023 and was driven by the West Cork co-ops.

‘We did a lot of work with farming organisations to get the message to ministers that reducing stocking rates would cost a lot of money and there would be a serious shortfall in income for many farmers if it dropped to 220kg Org N/ha that would be felt across the wider West Cork economy, and no subsides will recover that loss.

‘The repercussions came over the hill far faster than people expected. Most people didn’t realise the impact it would have. We saw farmers sell cows in order to comply last year and milk production dropped from November onwards as they tried reduce yields and get into lower nitrate bands.’

That drop in milk production was a wake-up call, he said. ‘Everyone is working together now but it took some until the turn of the year for the bigger co-ops to act. They thought it was a West Cork or County Cork problem before that.’

Vivian’s own farm is seeing the cost of it too as the farm was in an area where the permitted stocking rate of organic nitrogen/hectare dropped from 250kg to 220kg. ‘We were stocked at 241kg N/ha now we’re 215kg N/ha. We’re producing 81,000 litres less and we dropped 16 calves and 16 stores out of the system to hold cow numbers high. That’s a lot of money sucked out of cash flow. Between the loss of milk and cattle sales we’re down about €64,000 in income compared to last year and that’s a conservative figure.’

There are a few hidden costs as well.

‘We’re 12 tons less self-sufficient in phosphorous because of derogation. So, we had to buy that in instead. That was something that surprised me as I thought we were going to be reducing chemical fertiliser. Our nitrogen use is more or less the same but we’re using one third less of it compared to before.’

Vivian said they are getting a handle on how to use protected urea but he knows it’s a product farmers have been frustrated by this year. ‘It’s disappointing really how protected urea hasn’t worked for many farmers. We’ve done fine with it but it’s in our interest to help farmers understand it more. It’s a different product to the likes of 18.6.12 so we need to work at it and we need to get a handle on it. We were concerned about it on our own farm too but we noticed when we were grass-measuring that we had the same amount of grass but it wasn’t as green in colour as when we used other products. That’s what gave is confidence that it was working.’

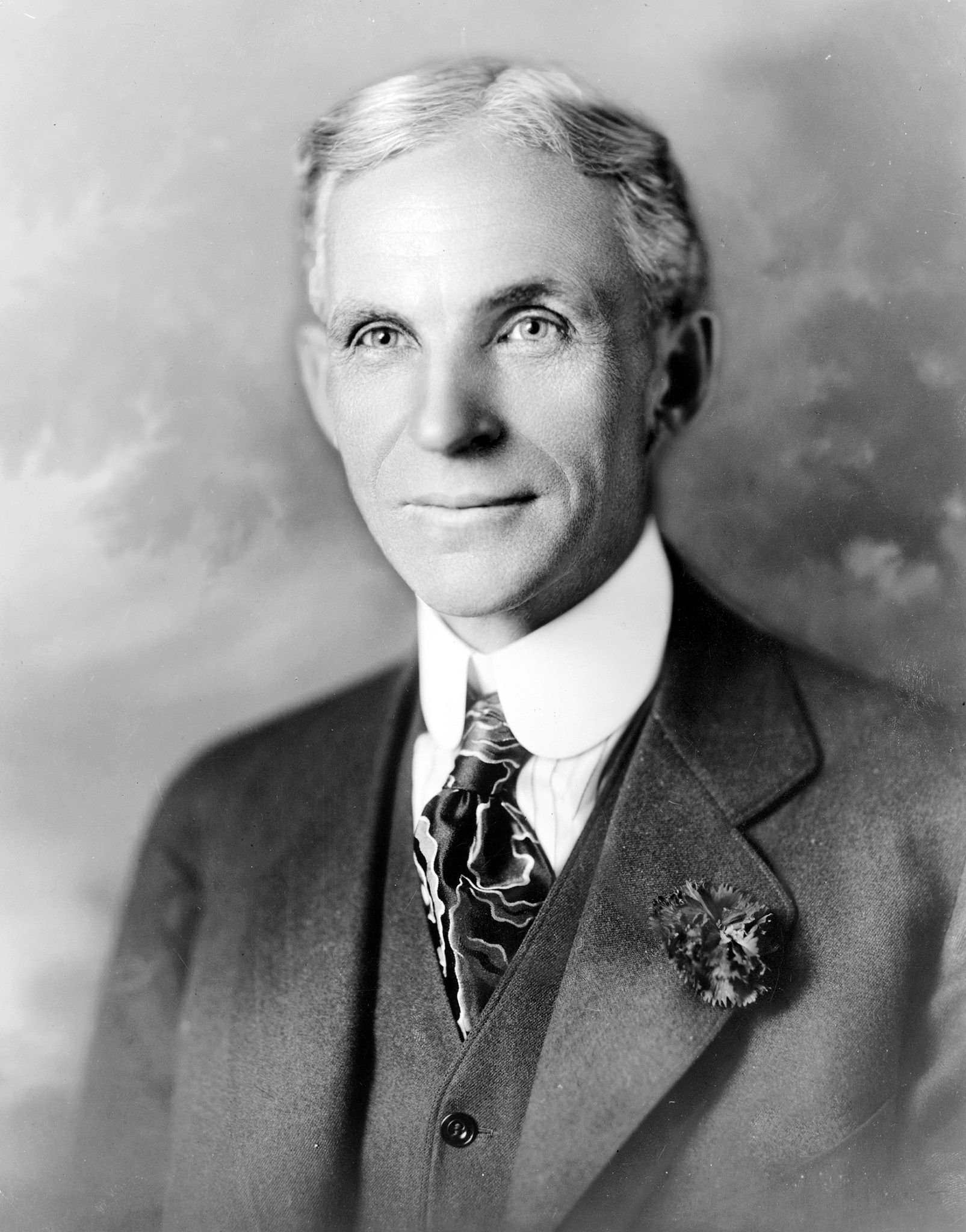

Vivian Buttimer’s farm at Crohane, Ballinascarthy is known as the Ford Homestead and is where William Ford, Henry Ford’s father, left from in 1847. The exact location of the homestead wasn’t known to him until the early 90s.

Henry Ford came back to Balinascarthy in 1924.

Henry Ford came back to Balinascarthy in 1924.

‘We knew they were in the valley somewhere but we didn’t know it was in this yard until Ford Bryan, an American historian with connections to the family, tracked it down in 1994. He was here in the yard but it wasn’t until he went back to America that he was able to work out which old building was the original dwelling. Henry Ford’s father was born in Madame (the area between Ballinascarthy village and Clonakilty Golf Club on the N71 road), and they were poor people paying an English pound an acre every six months. We have the lease here that they had in Madame. We know they could neither read nor write because the lease was marked with an X.’

The Ford family split in 1818 and they moved back up here before emigrating. William’s two brothers went out in 1832 and they got 80 acres each in Michigan. ‘They had to clear it and keep a census of what they produced every year. That was a condition and they had to be productive in the government’s eyes and they were given that land for free and they were free of landlords after that. They lived the American dream.

‘Three generations including Henry’s grandmother, aged 72, left this yard on three ponies and traps and made their way to Queenstown before sailing across the Atlantic and down the St Lawrence River.

‘Henry Ford came back in 1924 to Ballinscarthy, 70 years after his father had left and the map of the farm here at Crohane is in the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan. I’m the only one of the family not to have gone over yet. Maybe when I’m finished with the boards, I’ll get a chance to go see it.’